Previously, I explained the difference between learning bounded and unbounded subjects. School is bounded. Life is unbounded. The difference is critical.

In today’s lesson, I’d like to shift from search strategies to routines. What’s the best routine for studying?

The correct answer is that the perfect routine is one you can stick to and will let you reach your goals. Everyone has different personalities, constraints and preferences—so the perfect routine will be different.

That’s true, but it’s also unhelpful. Obviously some routines are better than others, even if we’re all unique.

Instead of specifying an exact routine—let’s look at the ingredients any such routine would have. Get the essential recipe right and the spices are up to you.

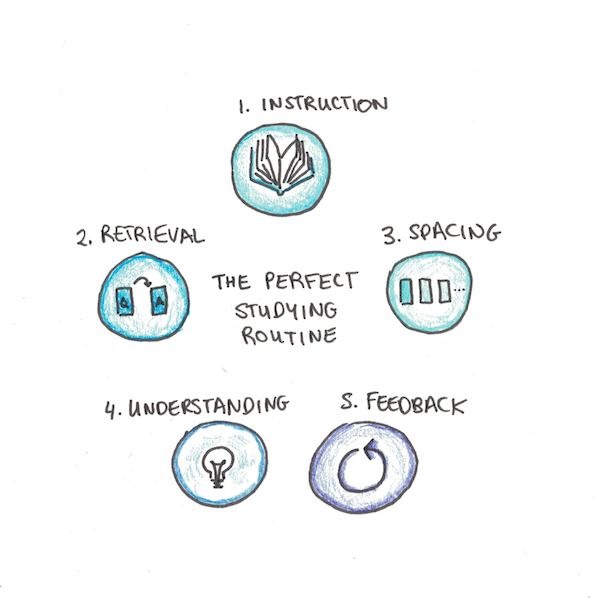

Recipe for the Perfect Routine

There are five main ingredients to include in any studying schedule you could dream up:

- Instruction

- Retrieval

- Spacing

- Understanding

- Feedback

There are few subjects where omitting one of these is safe. Conversely, get all five, and the rest is mostly fine-tuning. Let’s look at each:

1. Instruction — Avoid Trial-and-Error

This is the most obvious part. Instruction can be lessons, books or tutoring.

The reason to have instruction is to avoid trial-and-error. For some subjects, the trial-and-error is so difficult that nobody seriously attempts learning it without help. Rediscovering Newton’s Laws of Motion through personal experimentation is unlikely.

But even in more typically self-taught subjects, instruction helps. Being shown the right way to swing a golf club, hold a paintbrush or conjugate a verb can save enormous time over random experimentation.

2. Retrieval — Knowledge in Your Brain, Not the Book

Retrieval means deliberately dredging up knowledge from your mind—not just passively exposing yourself to it.

Countless studies show retrieval practice works better than passive review. If you’re going to use the knowledge in a specific place, practice in that place. Do practice tests, work on real problems and apply it.

3. Spacing — Once is Not Enough

Spacing is the idea of repeated reviews, spread out in time. It’s one of the most robust effects in cognitive psychology, benefiting many subjects.

The mechanism is less clear. Consolidation via deep sleep may play a role. Other theories suggest activating knowledge from different prior contexts makes more robust cues for retrieval (e.g. studying it from both your class and from home, gives two starting points to recall a fact.)

Regardless of how it works, its effectiveness is certain. A good routine needs to cover old knowledge along with new.

4. Understanding — Never Memorize What Needs to Be Understood

The goal of learning is for things to make sense. If something feels like an arbitrary collection of facts, that’s a sign you aren’t investing in understanding it.

Failures to understand can be fixed. The Feynman Technique remains my most popular studying advice. The method is simple: explain the confusing idea to yourself, as if you were teaching it. When you get stuck, find a textbook or teacher and you can now ask a much more specific question.

Not all understanding needs formal methods. With understanding as a goal, you change how you learn. The question stops being, “How do I cram all of this into my head?” and becomes, “How do I make all of this obvious?”

5. Feedback — Know Your Mistakes

Feedback is obviously useful. But there are some common misconceptions.

The first is that feedback has to come from people. This is false. “Did that work?” can often be answered directly from the environment. Human feedback can introduce biases, delays and social difficulties, so it isn’t always ideal.

Flip the logic around: whenever you can get accurate feedback that doesn’t need another person, get it there first.

The other mistake is assuming feedback will fix all problems. Feedback helps, but only with the other four ingredients. Tons of feedback, unprocessed, can easily turn your studying routine into trial and error (omitting ingredient #1) or rote memorization (omitting #4).

Fixing the Recipe

To perfect your studying routine, look at what you’re doing now and see where your ingredients might be missing:

- You’re an amateur painter, but you’ve never taken a class. Reading books or watching people paint will give you new methods. Add instruction and you can grow a lot faster.

- You learn history just by reading a lot. No retrieval or feedback. Why not try writing an essay or have conversations with other history buffs?

- You work through a course, one lesson at a time. You get instruction, do practice problems and try to understand it all. So far so good. But you’re missing spacing—old units don’t get reviewed until right before the exam, when you’re already starting to forget. A ten-minute pop-quiz on previous topics can save hours of cramming.

Your Homework: Perfecting Your Studying Routine

Here’s your homework for today:

- Pick something you’ve been trying to learn.

- Go through each of the five ingredients. Which is missing or weak?

- What’s one way you could add it in?

- Go to the comments page and write down your response!

Bookworms almost never miss #1 (instruction), but often miss #2 (retrieval). Practitioners get #3 (spacing) and #5 (feedback) for free, but may miss out on #1. A lot of improvements to your routine can come from simply hitting all five.

Rapid Learner is my six-week learning course. This course covers all of these ingredients in more depth, along with other strategies for improving how you learn.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.