A reader wrote to me saying his confidence was destroyed. He used to be a good student, but for the last few years that’s started to slip. Recently he just failed an important exam, and doesn’t know what to do.

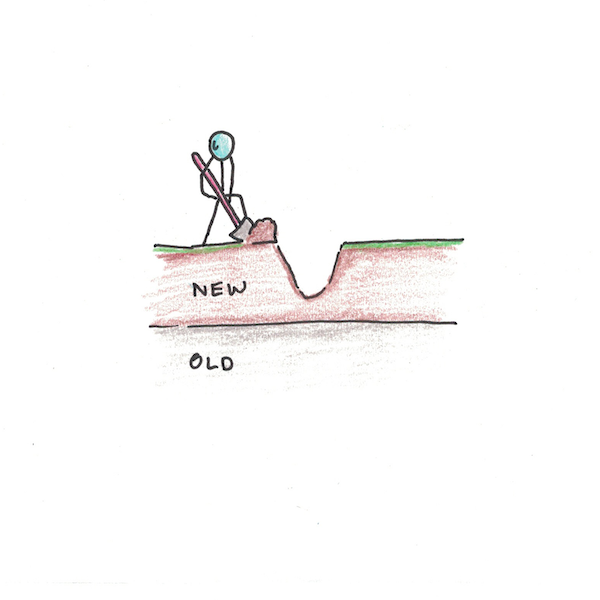

Rebuilding confidence is different from simply building confidence.

Building confidence, you’re trying to do something you’ve never been good at before. Joining Toastmasters, despite being terrified of public speaking. Trying Excel, even though you’re no good with computers. Taking a painting class, when you’ve only ever drawn stick figures.

Rebuilding confidence means you once were good. But now you’re not. In many ways, this is a harder hurdle to overcome.

The Framing Problem

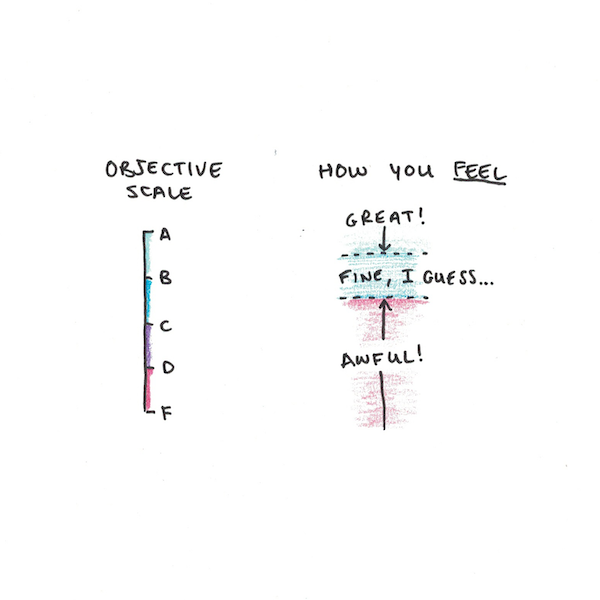

At its root, confidence is about expectations. Thinking you’ll do well is what it means to be confident. But the translation of a coldly calculated probability of success and the feeling of confidence isn’t always straightforward.

Framing effects occur when the same thing looks different depending on the surrounding context. The “B+” may feel wonderful for a perennially C student, but feel like a slap for the one who always gets As.

There’s ample evidence that framing effects influence how we feel and think:

- Studies show math and language performance are correlated. But people self-report as “math” or “language” types. Why? Because if you’re slightly better at one, it shifts your expectation for what counts as “good” for the other.[1]

- Big Fish, Little Pond effects show that your self-concept depends on your peers. If you’re a good student in a mediocre class, you feel smarter than if you’re merely a good student in an elite school.[2]

- Framing effects are common even outside of self-confidence. For instance, people irrationally change their strategy when the exact same problem is changed from “lives lost” to “lives saved.”[3]

Now we can see why rebuilding your confidence is so tricky. Your expectations are rooted in your past performance. Coming in even a little worse feels devastating.

Relearning and Rebuilding Confidence

Practicing a skill that’s gotten rusty feels similar.

I recently had my first conversation in Spanish after over a month spent intensively practicing Macedonian. I had let my practice slip in the year prior with the new book and baby, so I was probably already a little rusty. However, the added interference from a new language made things even worse.

The results were brutal! I could barely stammer out basic sentences, as I was trying to suppress Macedonian words that had recently become more salient.

In moments like these, doubts start to creep in. Maybe my Spanish wasn’t as good as I thought… How could I have let my practice slip so much… Maybe I’ve ruined my ability to speak this forever…

Of course, those doubts are exaggerated. Learning a new language frequently suppresses an older one. You just need to do the work of untangling the interference. Forgetting is normal, but relearning tends to be pretty fast.

Yet the way you feel isn’t always rational. A switch has been flipped, where something that once gave pride and self-confidence, now undermines your self-image. There can be resistance to rebuilding, as you want to distance yourself from discomfort.

Play Over Performance to Rebuild Confidence

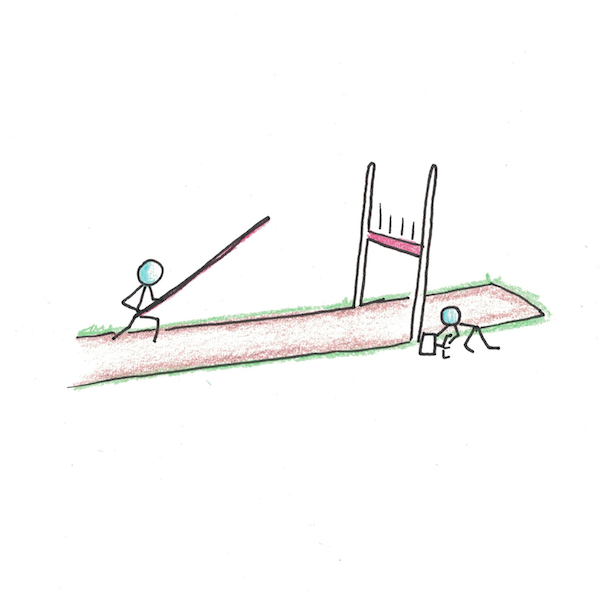

As we get better at a skill, we gradually shift our mindset from play to performance. Play is just for fun. Mistakes are forgiven and failure is part of the process. Eventually, we start taking ourselves more seriously as the rewards of success start to increase.

Rebuilding confidence requires deliberately dialing back into the play mindset. There’s a few ways you can do this:

1. Make failures painless.

This is a problem with some algorithms for spaced repetition. They make failure extremely painful. In some, if you fail a review, the card goes back to square one, as if you just started studying it.

From a memory standpoint, the back-to-zero approach seems implausible. If you forget something you’ve studied many times before, a failed attempt simply isn’t the same as starting from scratch. Ideally you’d do a few reviews, then the spacing would rapidly return to previous levels.

Subtle things like this, however, have an even bigger impact on motivation than memory. If you dive back into old reviews and get every card wrong, the failure is an extremely strong signal to stop.

You can make review less painful if your first tests are no-consequence practice tests. Put cards you miss aside and try them again for real later. Do warm-up exercises for low stakes before you put yourself under the spotlight to perform again.

2. Expect frustration and failure.

What makes failure sting is the expectation of success. Some of this expectation is set unconsciously, as in the framing literature I reviewed above. But in other cases you can be explicit about your frame.

If you start studying embracing the fact that you’ll fail, it doesn’t sting as much when performance suffers. Now you’re just studying to see what you know and what you don’t, rather than to get a good score.

Premature expectations of performance are a big reason why students don’t use effective studying techniques. They don’t feel “ready” so they stick to passive review instead.[4] The solution isn’t to study ineffectively, but to lower your expectations so that effective methods don’t feel too punishing.

3. Trust the rebuilding process.

There’s a peculiar kind of meta-confidence that goes along with learning well. This meta-confidence isn’t confidence that you’re going to do well, but confidence that you’ll eventually rebuild your confidence!

My Spanish difficulties didn’t worry me as much this time, because I’ve experienced this multiple times before. I remember trying to speak French for the first time after my intensive immersion in Spain—it was terrible! I couldn’t believe how much I had forgotten.

The problem in this case is that speaking similar languages involves both activating the correct word in one language while suppressing it in another. With practice, this gets easier. But add a new language, and this equilibrium can get disrupted. Now you always think of the word in one language, regardless of which one you’re trying to speak. The other word is still “there” it’s just being out-competed by the newly learned expression.

If you realize this, however, you can expect it and not have it frustrate you. Similarly if you expect relearning to involve a huge hit to performance but with faster relearning, the initial frustrations feel like hiccups along the way.

Even the Best Among Us Lose Confidence

As a young scientist, Richard Feynman felt he had burned out:

I would get offers from different places—universities and industry—with salaries higher than my own. And each time I got something like that I would get a little more depressed. I would say to myself, “Look, they’re giving me these wonderful offers, but they don’t realize that I’m burned out! Of course I can’t accept them. They expect me to accomplish something, and I can’t accomplish anything! I have no ideas…”

Surely You’re Joking Mr. Feynman, emphasis added.

His way past it, in the end, was to reframe his expectations:

And then I thought to myself … You have no responsibility to live up to what other people think you ought to accomplish. I have no responsibility to be like they expect me to be. It’s their mistake, not my failing.

Emphasis added.

Of course, the universities banking on him weren’t mistaken. Feynman had many great ideas, including the work that later won him a Nobel Prize and placed him with the greatest minds of physics.

It takes skill to strive ahead with confidence. But it takes character to continue on without it.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.