Sometimes the boring skills in life turn out to be the most important.

Case in point: the market for being really good at Excel is much larger than you think. I have a friend who does lucrative consulting work mostly on his ability to be better than you at Excel. Machine learning is trendy, but most organizations don’t need someone to run convolutional neural nets—they need someone to work spreadsheets.

Or consider another super boring skill that’s incredibly valuable: planning.

Most people are terrible planners. In fact, people are so bad at planning that psychologists have a name for it—the planning fallacy. The planning fallacy points out that people tend to be overly optimistic planners. Our projects take much longer and more effort than we anticipate.

Why Planners Succeed

We aren’t designed to be good planners. Our ancestors had little need for complex planning. Food couldn’t be easily stored, so you went looking for it when you were hungry. As such, nature didn’t make us great long-term thinkers.

One way our ineptitude at planning manifests is in what behavioral economists call hyperbolic discounting. The idea here is that when we need to choose between rewards right now and rewards in the far future, we’re much less patient than we ought to be.

Being able to restrain your impulses and think long-term is associated with success across many different metrics: health, wealth, education and more.

But the benefits go beyond simply thinking long-term. Life is complicated, and often what you need to do to have a better future is more sophisticated than a daily habit. If you want to advance your career, for instance, you may need to go to school or acquire skills, you may need to apply for new jobs or complete key projects. Each of these efforts requires considerable planning to achieve.

The 10% Rule: Taking Planning Seriously

The first step to becoming a better planner is simply to set aside more time for it. Since we’re evolved to be seat-of-our-pants doers, not patient planners, we need to counteract that urge by forcing ourselves to map out the path ahead.

Informally, I like to follow the 10% Rule, which says that you should spend, roughly 10% of the total time you anticipate for a project on planning the project. So if you were going to spend 100 hours on a project, you should spend about 10 hours planning it.

At first this seems crazy large. And, admittedly, this rule can be reduced for longer projects (especially those that might need intermediate planning as you learn more). Yet, for new project types where you lack experience, the time spent planning is often the most valuable.

Map Out Everything You Need to Do

Once you’ve dedicated the time to plan, the next step is to break down everything you need to do in order to move forward on a project. To be successful, the plan needs to be way more granular than most people make it.

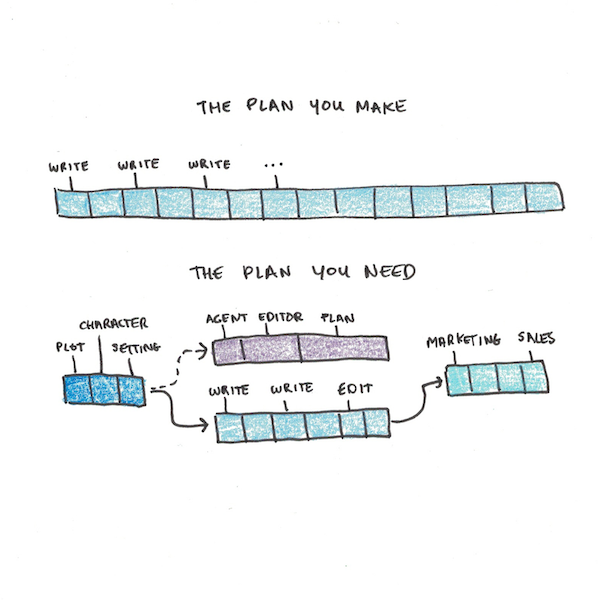

For most people, a project like writing a novel gets a plan like, “Write 500 words per day.” This isn’t a plan, though, just a daily habit.

A novel-writing plan, instead, would start by asking what we’re trying to do. Are we trying to reach out to a publisher? Are we going to self-publish? Or is this just for the desk drawer for practice? If we’re publishing, maybe we’ll need an agent, editor or reviewers?

How are we going to structure the story? Define the main plot? Fill out the character backgrounds and make the setting believable? Maybe your novel is set in a different city, will you travel there to get experience or work from books to fill in the scenes?

These questions aren’t there to provoke anxiety (although planning often is uncomfortable, which is why we don’t do it). Rather, they’re there to show that the end plan for writing a novel is a lot more complicated than simply writing every day. It may have discrete milestones for research, character building and plot development, not to mention any stuff that goes into making the project a success outside of merely writing the thing.

Why bother with all this effort? Can’t you just cross those bridges when you come to them? Yet most projects like this fail. The key to having yours be a success requires a little bit more planning than feels automatic.

Put the Plan in Your Calendar

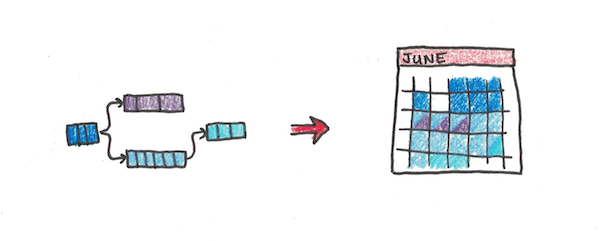

With a map drawn, you now need your itinerary. When will you start? How many days a week will you work? When do you expect to reach particular milestones?

All of this needs to be put in your actual calendar. You don’t need to break down a year-long project into daily increments, as this can be too tedious to update once there are inevitable changes. However, you should put down all of the key milestones. You should also include a weekly horizon showing your hourly time investments.

There are two main reasons for putting everything in your calendar.

The first is logistic. A lot of people start with a loose plan, “I’m going to do X over the next month.” But they fail to realize how many obstacles already exist in their schedule. Maybe they have a vacation coming up, or there are other deadlines that might interfere. If your plan never touches your calendar, you’re not forced to confront these conflicts until it’s too late.

The second is psychological. Actually putting the time in the calendar makes the plan real in a way that daydreaming doesn’t. Suddenly, a lot of vague and ambitious plans seem a lot more costly—“Oh wait, so I won’t be able to do anything in the evenings for six months to get this done?” This may seem discouraging, but pessimism in planning is actually good! If you see the difficulties in your plan and still want to go forward, you’re much more likely to stick to it than if the hardships show up belatedly.

Translate to Daily Actions

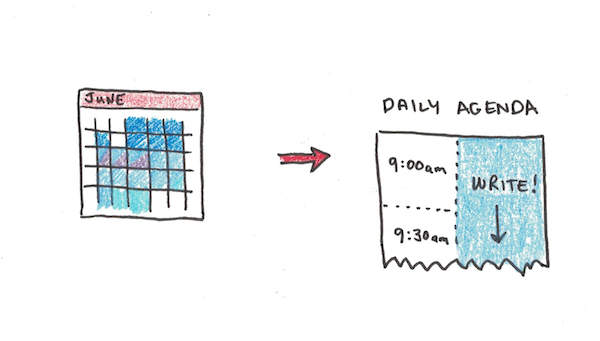

The final step of any good plan is that it should tell you what you need to do today. Not next week. Not tomorrow. Today.

Our hyperbolic discounting means that anything that’s more than a couple days in the future isn’t useful for motivating immediate action. And immediate action is the only kind that gets anything done.

You can go a step further and commit to particular hours for your plan. This is more useful when your schedule is already congested, and so a missed opportunity to take action might mean you fail to stick to your plan at all. When I’m busy, telling myself I’m going to exercise today is far less useful than telling myself I’m exercising right after I finish work, before dinner.

Still, at the very least, your plan should tell you what you have to do today to move forward. If you’re relying on a deadline that’s weeks away to motivate, you’re not going to stick with it.

These are just the basics. I haven’t covered some other useful steps, like implementation intentions, interviewing experts, metrics, precommitment and all sorts of other strategies. (For those interested in mastering this skill, consider my course, Make it Happen!) But even getting the basics right makes a big difference.

Planning, Not Procrastinating

If planning is so important, why does so much advice point in the opposite direction. We’re told to “just do it” rather than sit down and think it through.

I suspect the reason is that most people don’t do any planning. Instead, what they call planning is really just procrastinating. Musing about an idea instead of concrete action.

I hope, given the above description, you can see that the kind of planning that works is far from procrastinating. It’s an active process that requires research, scheduling and often facing up to the uncomfortable realities of real world achievements. If anything, planning is what’s being procrastinated on—you avoid figuring out what the real thing you need to do is, because it’s safer to daydream about it instead.

Making plans may not be the most exciting skill, but it’s one of the most important. Ultimately, the future belongs to those who plan for it.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.