Recently, I published my Complete Guide to Motivation. The guide covers the research landscape on motivation from psychological, neuroscientific and economic perspectives. One of the key researchers I highlighted was Piers Steel, a leading expert on procrastination.

Since I found his research findings so helpful in my own understanding of procrastination, I invited him to sit down with me to chat about it. What follows is our deeper look into the research behind motivation and procrastination.

Below I’ve highlighted a few parts of our conversation:

Why Do We Procrastinate?

On why we can’t seem to motivate ourselves:

At the simplest level, it’s three factors and one of them is the most important. …

Your self-confidence or self-efficacy. Your feeling that I have the ability to do this. If you feel like “Yeah, I got this,” that really helps. …

If you find the task unpleasant that’s another, of course, pretty obvious element in motivation. …

But the last one, and this is the one we miss most is time and your sensitivity to time. We’re very sensitive to when rewards are realized.

What does research show is the best way to deal with procrastination:

The easiest and fastest way, which most people don’t mind, is distancing temptations. … If we can delay our temptations by ten, fifteen, twenty seconds, that’s enough to take the oomph off of them.

What Steel calls the “nuclear option” that works really well (but nobody wants to use it):

That’s called precommitment. … If you really want to get something done and you’re willing to make a bet, and if you don’t do it, you give me $10,000 and if you do do it, you give me a handshake, that will get it done, 100%.

But can telling other people about your goals actually backfire? Steel explains:

If I’m telling other people, “Yeah I’m going to start exercising,” I’ve actually done myself motivational damage. Because it’s vague and non-specific and I get a certain satisfaction or virtue by saying it. And that actually satisfies my need to exercise somewhat. You might sort of think of this as motivational pornography, where the image or verbal takes the place of the real.

Self Control and the Right Way to Set Goals

Why we’re terrible at long-term planning (and why this wouldn’t have been a problem for our ancestors):

A week is actually, motivationally a long, long way off. A couple days, yeah, that’s pretty much it. And we’re the superstars of self-control of the animal kingdom. Our capacity to wait for a day or two is mind-blowing, compared to the animal kingdom. But when you have a semester-long paper or a retirement plan or a four year degree, two-days just don’t cut it. But it really matches well for when the panic comes in, when your natural discount has activated.

But this is all natural, if you went back to hunter gathering, you’d fit perfectly. There would be no procrastination.

Motivation comes with an eye-dropper when you want it, and a firehose at the end. What we want is a nice tall glass of motivation, but we don’t really have that. We have this really messed up system.

What does research say about the most effective way to set goals?

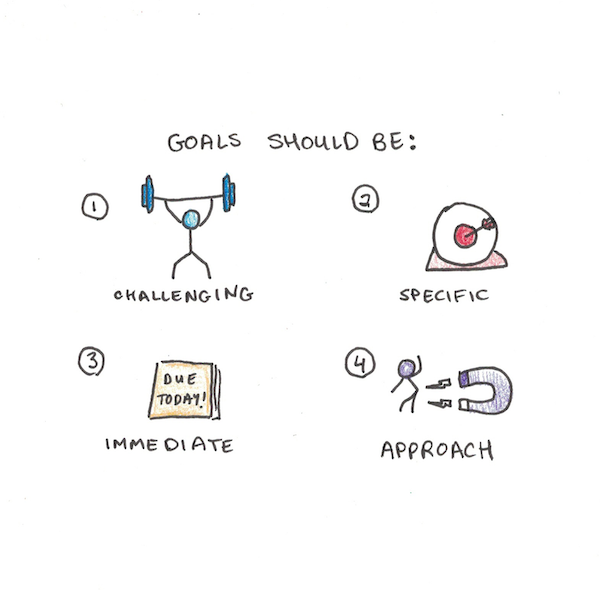

We know the mechanics behind proper goal-setting. I even tried to make a new acroynm to compete with SMART goals, CSI-Approach (Challenging, Specific, Immediate and Approach Goals).

One of the worst goals you can have is, “I’m not eating candy”, because how can you be “soon” not eating candy. You can’t. What would be better is, “I’m going to eat more salads.” or, “When I want to snack, I’m going to eat carrot sticks.”

From Temporal Motivation Theory we have expectancy, value and time. Challenging has to do with expectancy and value, and goal commitment which has been studied a lot. If you have a goal but you’re not committed to it, that really matters a lot. Do you feel committed to it? Can you reshape it so that you’re committed?

The Challenging part is to make it seem in the realm of the possible, but also to make it worthwhile.

Specific and immediate is the limbic system. Were trying to move it out of the realm of the abstract, into the concrete. “I want to do well” or “I want to lose weight” is really abstract. What exactly do you want to do, as if you’re giving someone else? You want to know where that finishing line is. Then you want to play with the immediacy. Limbic system if it’s short enough term, that’s what will keep the motivation up.

We need it to be approach because we can’t have deadlines around avoidance goals. We put all those elements together and we have a working goal.

[What matters is that] you can visualize yourself doing it. … Because otherwise you’re in slippery goal land. If you don’t have definite goals, in definite words or definite hours, then you’re not going to be moving forward on it.

How can you motivate yourself better? Can you?

Sometimes you’re not dealt the best set of hands, but it doesn’t stop you from playing those cards the best you can. You’ve got to learn how to play those cards—your motivational repertoire—and maybe even know which cards you can kind of do better with. If you’re not getting enough sleep, … you can’t go wrong by improving your sleep. Are you eating well? These are all basic elements.

This kind of idea that you can have complete control over the outcome, you can’t. But, just like a poker game, you can maximize your chances.

Why We’re Bored, and Why Wanting Something Doesn’t Always Lead to Taking Action

On the evolutionary significance of boredom

If you had to design a creature, and you want it to disengage from an activity because it was no longer purposeful, what emotional state would you put in that creature? It might be called boredom. Boredom is our natural state of us saying “disengage, this has no significance” and unfortunately it gets activated for a lot of things that are, in the long-term useful to us.

Effortful attention is a difficult thing to do, because you’re trying to override a system that says that “this is not actually relevant.” Your energy level really determines how well you can pay attention to things. … If you can just reorganize your day to do your hardest work when you have the most energy, you’ll find you’re accomplishing more than your competitors and you’ll have more time off.

Effort is often contingent on how much energy we have. We tend not to respect our times of the day when giving effort is less effortful.

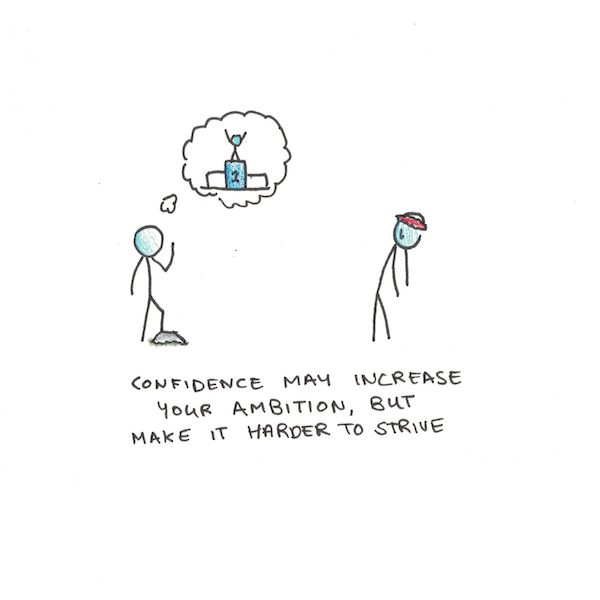

Motivational theories often rely on combinations of expectancy and value. These state that you’re motivated to the extent that you both value an outcome, and deem it likely you’ll achieve it. But, Steel notes that the research is actually split on whether confidence is an unalloyed good:

There’s this idea of goal choice versus goal striving. The motivations that get you to choose a goal aren’t the same as the ones that get you to strive toward it. You could want something, and want it quite badly, and still find it difficult to find the motivation to do it.

Entrepreneurs tend to be more confident, than the everyday. But they find the most confident entrepreneurs tend to be the least successful. You have to have confidence, but also respect for the competition. I can do this, but it won’t be easy. Balancing those two things works really well.

Do listen to the whole thing. And, while you’re at it, we now have 100+ podcast episodes. If you like it, please give it a rating so more people can find out about it.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.