Flashcards, especially in their digital incarnations, are some of the most powerful learning tools. They can also easily be a complete waste of time.

Powerful, because retrieval and spacing are key to memory. If you want to learn a topic with a lot of stuff to memorize, flashcards will help you do it better than almost anything else. Mnemonics are trendy, but for medium-to-long-term purposes, flashcards are probably better.

It’s also easy to waste your time with flashcards. You can spend a lot of time memorizing something you don’t need to, or fail to memorize the important things you do. Flashcard practice can also be a convenient way to avoid doing the real thing you need to learn. Some subjects may not be amenable to flashcards at all.

Let’s try to untangle these seemingly contradictory views…

In Favor of Flashcards

Flashcards work via simple retrieval practice. You have a question on one side, answer on the other. By trying to recall the answer before looking at the back, you strengthen the memory link between the one and the other in your mind.

Retrieval practice is well known to be one of the most effective studying methods. While flashcard study isn’t the only way to practice retrieval, it can be a convenient one for subjects that are factually dense.

Spaced Repetition Systems (SRS) such as Anki or Supermemo enhance this basic technique by automatically scheduling reviews. The spacing effect, that repeated exposures spread out through time enhance memory, has been known since the dawn of experimental psychology. Once again, there’s clear evidence spacing works.

A common claim of SRS is that they optimally space out reviews. With an exponentially increasing delay between successful reviews, this allows you to keep adding new flashcards without the burden becoming unmanageable. While this review schedule is convenient, the scientific evidence isn’t so clear-cut as to it being better than evenly-spaced reviews.

Flashcards also compare favorably to mnemonics, which is often what is taught in memory-enhancing courses. Mnemonics tend to be somewhat narrower in their applications, and since the rely on the declarative memory system, they may result in less automatic and enduring memories than repeated retrieval practice. (Of course, if you can do both, that’s even better. But if I had to choose where to start I’d go with flashcards first.)

Flashcards have many passionate advocates online, so if you google around a bit for learning methods, you’re likely to stumble across people who have made Anki their go-to tool for learning languages, medicine, math and more.

Flashcard Failures

Okay, if flashcards are so useful, and the two principles on which they’re based (retrieval and spacing) are so well-justified, what’s the problem?

There are a few major traps you can fall into when applying flashcards:

- You grab off-the-shelf flashcard decks, rather than make or edit your own.

- You design the cards badly. This leads to either memorizing useless stuff or failing to learn what you actually care about.

- Memorization substitutes for understanding.

- Flashcards substitute for doing real practice.

Let’s look at each of these pitfalls briefly.

1. Off-the-Shelf Flashcards

The appeal of a premade flashcard deck is obvious: making a deck takes time and so grabbing one off-the-shelf can save dozens of hours. The downside is less obvious. A lot of premade decks are terrible, and only work with considerable editing.

One resource I used while learning Chinese characters was the Mastering Chinese Character decks. There were a series of ten of these and they benefited from having native audio and images. Plus there were a lot of cards—well over 10,000 in total.

Except the deck had numerous problems. The language was quite formal for beginners, resulting in me learning a lot of not-so-common ways to say things (and thus being misunderstood). There were also a subset of cards that went from single-character pronunciation to the written form. This doesn’t work, because each sound in Mandarin represents multiple characters—是,市,士 are all common characters that are pronounced shì.

I don’t regret using this deck, but it did require a lot of editing (including filtering out the broken cards). Most of the time, however, you won’t be so lucky. The decks you download will end up wasting you more time than making your own.

2. Bad Card Design

There’s a subtle art to designing a good flashcard:

- Each question should have one and only one correct answer. (Something violated by my Chinese deck as mentioned.)

- Questions should either have as little unnecessary context as possible, or redundancy. A vocabulary word alone, or used within a few sentences (each on different cards) are better designs than a single sentence. Why? Because you learn to predict the answer based on the surrounding context even if that won’t be there when you need to use it in real life.

- Questions should be simple. Complex problem solving isn’t well-suited to flashcards. Better to break apart complex problems into multiple steps, or simply forego flashcards altogether in favor of solving real problems.

- Questions should be something you actually need. Just because you can memorize something doesn’t mean you should.

A sloppy way of making flashcards is simply to copy and paste stuff from your classes into a Q&A format. This can be fast, but it ends up making many cards that end up violating these rules. The result isn’t memory but a mess.

3. Memorization Substituting for Understanding

I used to be a strong opponent of rote memorization. My views now have evolved, as I see that memory and understanding are probably on a continuum rather than distinctly different things. Knowing many facts is often needed for understanding, and so flashcards shouldn’t be seen as the enemy of insight.

Nonetheless, there’s often a tendency to take a difficult problem of understanding and try to replace it with a system of memorization. Difficulty in learning deep programming ideas, for instance, get swapped out by flashcards to memorize syntax. Except syntax is fairly easy to look up and ideas are fairly hard, so this has the priorities exactly backward.

There do seem to be some people who can learn conceptual subjects through flashcards. However, I’m less optimistic that this is a generally good approach. For many deep subjects, solving lots of problems ought to be the first step, with flashcards used to master stubborn details that are often forgotten.

4. Doing Flashcards Instead of the Real Thing

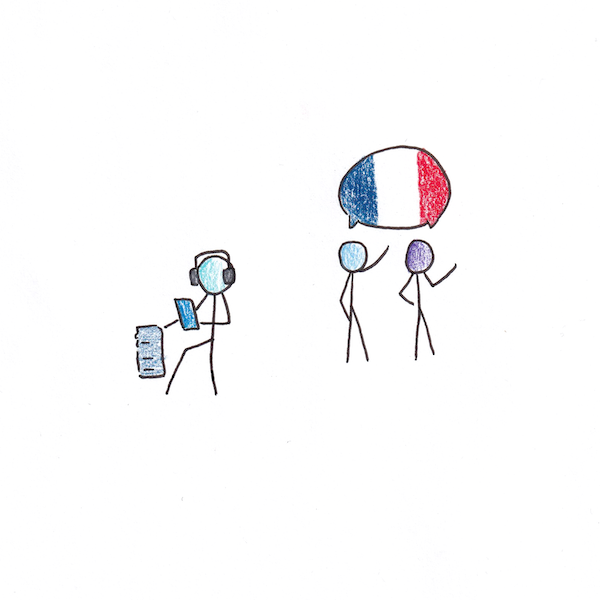

Flashcard fetishization reaches an extreme in language learning circles. I say this being someone who has made decks with tens of thousands of cards.

The logic seems to go like this: languages require a lot of memorization, flashcards are good for remembering things, therefore if I just do a lot of flashcards I’ll be fluent in a language.

The problem with the logic is the word “just”, flashcards are great for memorization. But using a language is much more complex than just spitting out translations. Since actually speaking a language is more effortful than flashcards, typically, they can end up being a fake substitute to the real thing.

My own experience with using flashcards in language learning has varied. I didn’t use them much at all with Spanish, as I found I was able to remember words well enough from real conversations. I used them heavily while learning Mandarin, but always alongside real conversations. My more recent Macedonian project was in-between—I made a much smaller deck of around 2000 cards which was really helpful for vocabulary, but my total time spent on flashcards was a distinct minority of my studying time.

Should You Use Flashcards?

If you’ve never used spaced repetition systems before AND you have a memory-intensive subject to learn (language, law, medicine, etc.) the answer is probably yes. You should at least give them a shot because they really are vastly superior to the passive review techniques that students typically use.

If you’ve tried them before and they didn’t seem to appeal to you, chances are you either designed the cards badly or your judgement was correct and other forms of practice might be better. While there’s always a risk of using a tool incorrectly and mistakenly thinking it doesn’t work, there’s also often excessive enthusiasm from devotees of a particular technique.

If you’re a flashcard aficionado, I would go forward, but with caution. Are you doing the real work to develop understanding in the areas that need it? In complex skills like speaking a language or medical diagnosis, are you using flashcards to supplement or substitute the real practice you need to get good?

My feeling about flashcards is similar to my views on most learning methods. They work well when used appropriately. The trick is to have enough self-awareness and understanding of your subject to know what’s appropriate and what’s not.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.