As many of the readers here probably know, I’ve been a long-time fan and friend of Cal Newport. We co-instruct two online courses and we’ve shared more conversations than I can count. Cal also coined the term “ultralearning” and pushed me to write my book, so his influence on my career hasn’t exactly been minor.

So of course, I was very excited to hear that his latest book, A World Without Email, had reached the New York Times bestseller list in its first week. I just finished reading my copy and I have to say I think it’s Cal’s best work to date.

Is Email Really So Bad?

The title of Cal’s book is provocative. To be honest, when I first heard he was writing a book about eliminating email, I was a little confused. What’s wrong with email?

Heck, if you’re getting this essay delivered via my newsletter, there might be some irony here. I’m sure Cal is also aware of this tension—tens of thousands of readers are also on his email newsletter. Beyond that, Cal and I mostly communicate via email these days, so if the ideal of the book was zero email usage, we’re both failing miserably.

Once you start reading, however, the message of the book is clear. What Cal is against isn’t email per se, but what he terms the “hyperactive hive mind” workflow that it enables. This is the workflow which involves numerous back-and-forth pinging of email in order to do collaborative work. Endemic in big organizations, this workflow is unproductive and it is making us miserable.

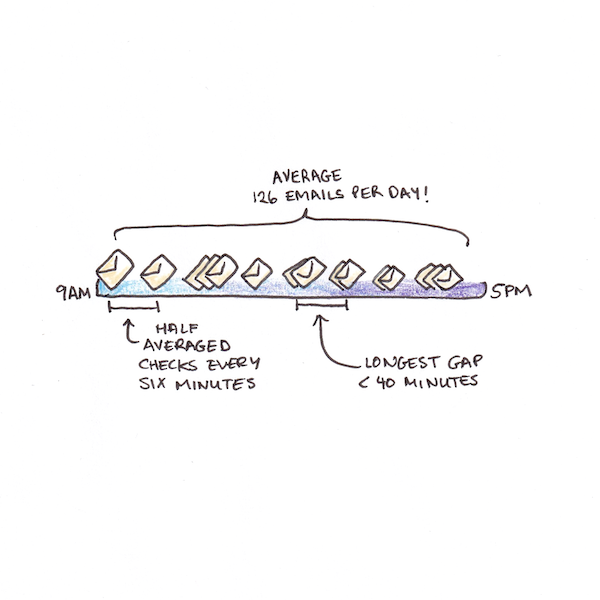

Cal shares anonymized data gathered by the time-tracking software RescueTime and it isn’t pretty:

- Half of users check communication applications like email or Slack every six minutes or less.

- The most common average checking time was once every minute.

- For half the users studied, the longest unbroken period of work was no more than forty minutes, with the most typical longest time being only twenty minutes.

- More than two thirds of users never experienced an hour without an interruption.

- For business users, average email volume was 126 messages per day.

Earlier productivity writers, notably Tim Ferriss in his bestselling 4-Hour Work Week, argued we could reduce email’s impact with techniques like batching or sending out autoresponders to inform our colleagues that we were only checking email twice a day.

Cal believes these measures often fail because once your organization has adopted the hyperactive hive mind workflow, it’s hard to opt out. Your boss and peers are also sending emails back and forth frantically, so being the one person who ignores this creates friction.

What we need, then, isn’t just better email habits but totally new workflows for handling our collaborative work. While Cal’s book Deep Work argued for the benefits of depth from a largely individual perspective, A World Without Email could be said to extend this reasoning to the problem of coordinating work across an entire organization.

Knowledge Work Hasn’t Had Its Productivity Epiphany

Coincidentally, prior to reading Cal’s books, I had been engaged in a mini-project of my own to investigate the origins of thinking on productivity. This had me reading big textbooks like Daniel Wren and Arthur Bediean’s The Evolution of Management Thought, and Frederick Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management.

I can see clear parallels between Frederick Taylor and Cal Newport. Both saw their respective working environments as being horridly inefficient. Both saw the problem as stemming from coordination failures—individuals might act out of their own interest, but collectively end up getting much less done than they could ideally. Finally, both suggest the prescription is to research and design better ways of working to get more done with less waste.

Cal downplays his similarity to Taylor for the probable reason that Taylor hasn’t always been viewed fondly through the lens of history. I tend to be of the view that Taylor was unfairly vilified, so I tend to see the comparison more favorably. Still, I think even if you were a critic of Taylor’s time studies of productivity (where he would sit next to factory workers with a stopwatch to find out optimal movements and productivity levels), the critique largely wouldn’t apply to Cal. What’s being suggested isn’t turning us into maximally-efficient automatons, but taming the hive mind so we can actually get our work done in peace.

Via this comparison, however, we can see that Cal sees our current working setup as being akin to the pre-Taylor world of manufacturing. One in which production processes were ad-hoc and disorganized and productivity was abysmal. Following Taylor, Drucker notes, manufacturing productivity increased fifty-fold, so we can see how far Cal thinks we are from the productivity frontier.

Unintended Consequences of Technology

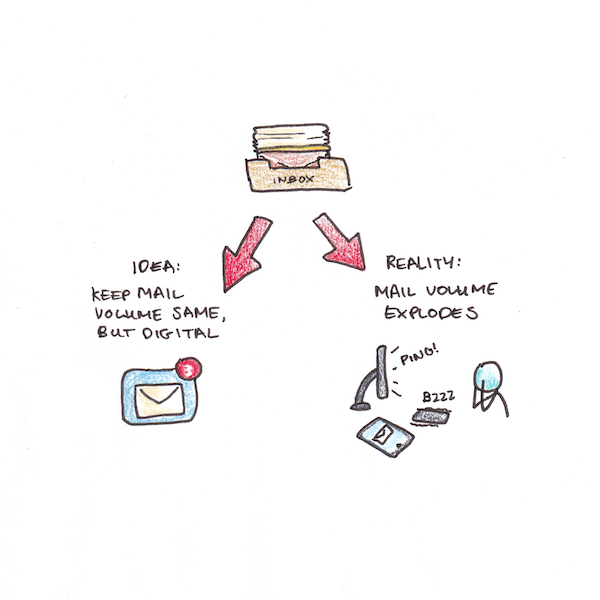

A recurring theme of A World Without Email is that technology isn’t neutral. Email didn’t just arrive in workplaces as a more efficient way of sending letters. Instead, it radically changed what messages were sent and, ultimately, how we performed our jobs.

This is a theme that runs through Cal’s earlier work, Digital Minimalism and his long-standing critiques of social media. Adding the “Like” button to Facebook was originally intended to declutter comment spaces, preventing redundant “Nice!” or “Cool!” in response to photos. But the consequences were extreme, suddenly allowing the services to provide the steady drip of social approval humans crave.

The problem, as Cal sees it, is that once you decide on email as the primary vehicle for collaborating with coworkers, you unavoidably slip into workflows that involve checking your inbox for new messages every three minutes. Cal’s addition to Marshall McLuhan’s “the medium is the message” might be interpreted as “the technology is the workflow.”

I particularly enjoyed this book because it made much heavier use of Cal’s computer science background. Claude Shannon, information theory, asynchronous communication channels and Nash equilibria are woven into Cal’s arguments. Computer science references aren’t typically what people are looking for in a book like this, but it was nice to see Cal leaning on his academic expertise.

What’s the Solution?

Cal’s suggestions are less radical than the title of the book. While Cal avoids making one-size-fits-all recommendations, his general approach is to replace the free-form ad-hoc collaborative style enabled by email with much more structured processes.

Cal writes fondly of tools like Asana and Trello, which can help get tasks off of email and onto more organized project boards. Discussion, then, becomes something you tune into when you’re ready to work on that task, not something that constantly interrupts unrelated work. Programming productivity paradigms like scrum and agile development also feature strongly, as the more disciplined communication habits have already shown dividends there.

The world Cal wants to envision doesn’t seem to do away with email entirely, but rather is one where email isn’t the main tool for getting your work done. That’s a vision I can wholeheartedly endorse.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.