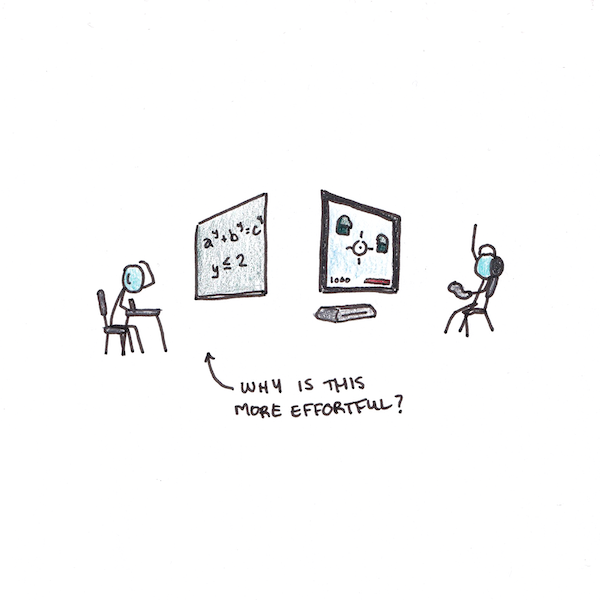

Why is it harder to watch a physics lecture than Netflix? Why does a cognitively demanding activity, like playing a video game, create a pleasurable state of flow, while math problems rarely feel that way? What makes something effortful?

At first glance, these questions seem too obvious to ask. Of course video games are less effortful than math problems—video games are fun!

Yet, I think an understanding of effort is supremely important. Many of the goals we want to accomplish will require a lot of it. If we have the wrong theory for how it works, many of our systems will fail or otherwise be poorly designed.

The Failure of a Theory

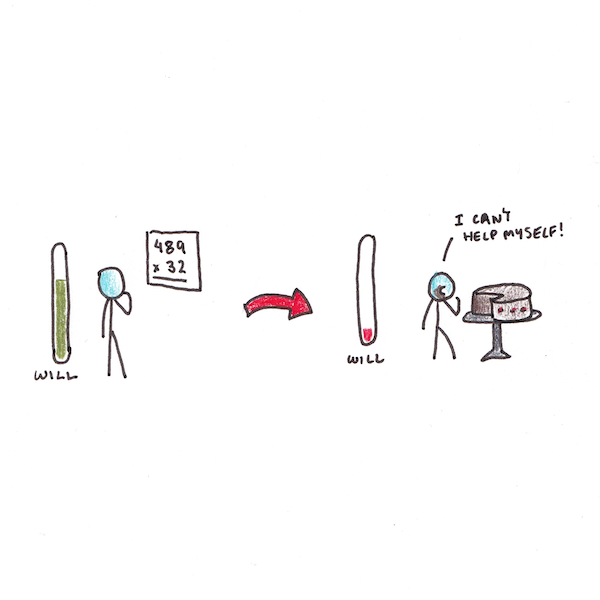

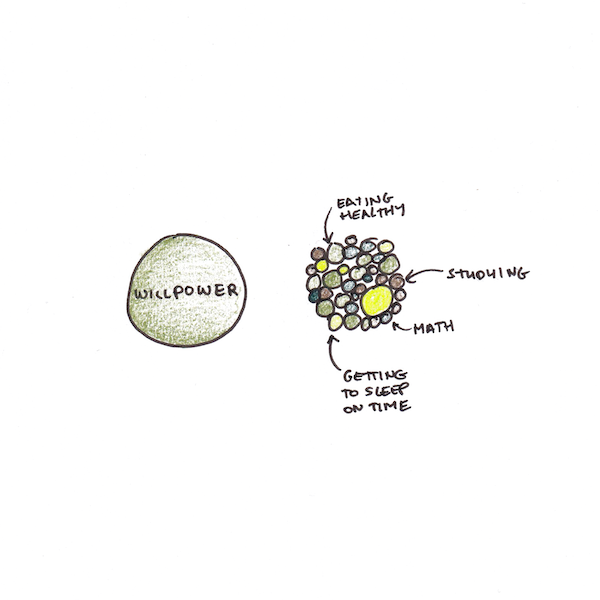

Unfortunately, until recently I couldn’t find a satisfying explanation of how effort works. The dominant model was Roy Baumeister’s ego depletion theory. This argued that willpower was a resource. Use it up and you (temporarily) have none left. Like a muscle, however, it could be strengthened.

Yet, ego depletion theory was a major casualty in the replication crisis. Baumeister’s preferred explanation for the source of the resource—glucose—ended up being wildly implausible.1

The theory was attacked on psychological grounds. Giving a reward could increase persistence, suggesting it wasn’t a physical limitation.2 Changing beliefs about willpower could also alter performance—another strike against a capacity constraint.3

Effort as Opportunity Cost

This is why I was so excited to read the paper “An Opportunity Cost Model of Subjective Effort and Task Performance” by Robert Kurzban et. al.. They suggest a new way of thinking about effort in terms of opportunity costs. From the abstract:

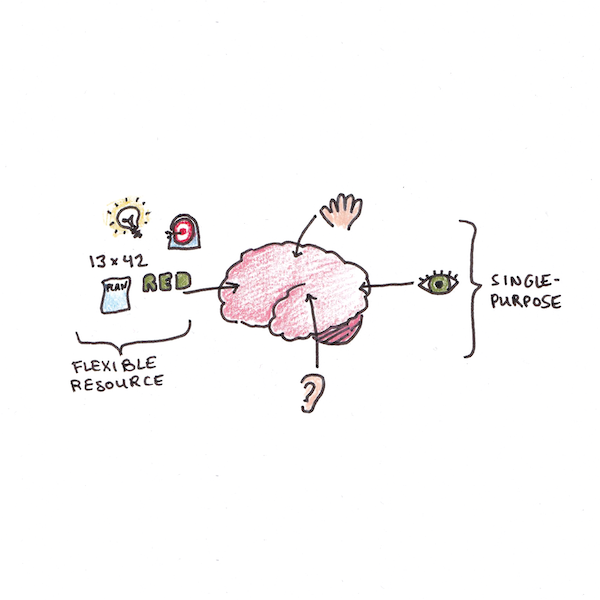

Specifically, certain computational mechanisms, especially those associated with executive function, can be deployed for only a limited number of simultaneous tasks at any given moment. Consequently, the deployment of these computational mechanisms carries an opportunity cost – that is, the next-best use to which these systems might be put. We argue that the phenomenology of effort can be understood as the felt output of these cost/benefit computations. In turn, the subjective experience of effort motivates reduced deployment of these computational mechanisms in the service of the present task.

The idea here is that the brain has many different functional centers. The part at the back of your head, called the occipital lobe, processes vision. At the side, there’s audio processing and language comprehension.

A lot of these functional centers are more-or-less single-purpose. Your visual cortex can process input from your eyes, but it can’t suddenly switch to help you with hearing something better, in case you’re in a dark room and want to devote more bandwidth to listening to an audiobook.

On the other hand, the frontal cortex, which includes centers believed to control central executive processing, is more flexible. It also makes connections through the basal ganglia, similar to the motor loop, which suggests that it may also be partly responsible for the experience of thoughts happening one at a time.

Kurzban and his co-authors argue that since the executive has many possible uses, it would be adaptive to have a system that ensures it is being applied to the most valuable activities. This experience of the cost-benefits of using this fixed resource would manifest itself as effort. When your current activity doesn’t feel like a good use of limited mental bandwidth, you feel like doing something else (like daydreaming or playing with your phone).

Computer Time Sharing vs Fuel Tank Metaphors

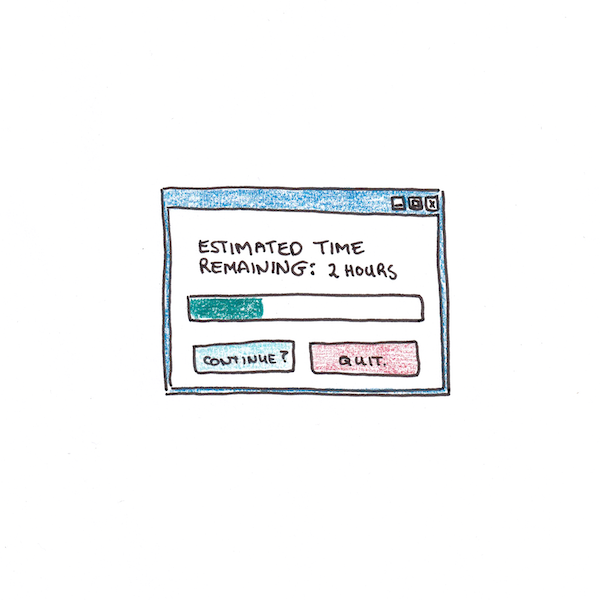

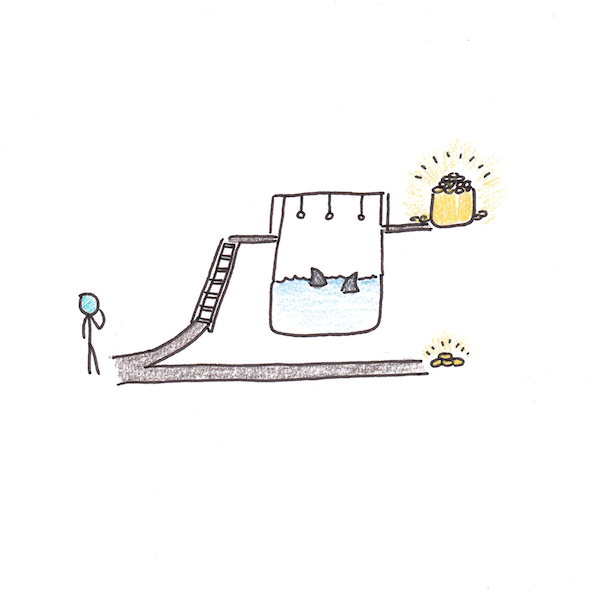

While ego-depletion is like a fuel tank, opportunity-costs are like computer time sharing. The computer resources don’t get depleted or used up, but they are constrained, and thus effort would be the experience that what’s occupying your executive processing just isn’t worth it.

If you’re like me and you remember when computers were slow, you have had the experience of trying to do something with a computer that’s running a major background process, like a backup, virus scan or rendering operation. You want to play a game or watch a movie, but the game depends on the same computational resources as the background process, so you have to decide whether to shut it off or wait until it is finished.

This paper argues for a similar process, except that these opportunity costs are experienced as effort rather than conscious decisions to allocate resources.

Applying This Model of Effort to Your Goals

What does this model of effort say about striving that a resource theory gets wrong? I can think of a number of important implications:

1. Effort Depends on Alternatives

How effortful something feels will depend on what it is being compared against. Thus it is more effortful to work with your smartphone nearby, thus cuing you to the possibility of quickly going on Instagram, than it would be if that cue wasn’t present.

This suggests to me an alternative mechanism for why habits can become easier. Since habits, in the sense of completely automated behavior, don’t really apply to complex routines like working out or studying, it’s an open question how effortless they can become. However, if we see effort as a comparison of alternatives, one thing habits provide is a reduced salience of possible alternatives.

Thus studying a math problem is much more effortful when, in moments similar to that one, you often play video games or surf the internet instead. Their salience is high and thus the opportunity cost of continued studying is high too.

2. Willpower Depends on Reward

The opportunity-cost model has a similar implication to Robert Eisenberg’s learned industriousness. Eisenberg’s theory was that when you get rewarded for effortful activity, the experience of effort itself becomes less unpleasant and thus you more easily choose high-reward, high-effort activities over low-reward, low-effort ones.

In an opportunity-cost framework of effort, we can increase our self-control by learning that certain actions yield positive results. The authors give the example of a smoker resisting temptation a few times, thus giving evidence that this is an effective strategy, and thus making it more likely to resist in the future. If persistence on a difficult math problem pays off with finally understanding it, you’ll find it easier to persist through frustration in the future.

3. Discipline is Specific, Not General

Both the resource and opportunity-cost theories of effort suggest our capacity for willpower may be improved, but they critically imply different ways this might come about.

Resource theories suggest the capacity is like a muscle. Thus, training on general-purpose disciplining activity will increase the capacity for any kind of activity that requires self-control.

An opportunity-cost theory, in contrast, suggests that what is learned when increasing self-discipline is the reward contingencies for certain activities. If you can establish that a certain activity is rewarding compared to alternatives, over time it will become less effortful.

The contrast between these two theories reminds me of the contrast between formal discipline in education and the notion that acquired skills are quite specific. In both cases, the intuitive (but, ultimately false) theory was that the mind was like a muscle, with general-purpose training effects. If the opportunity-cost theory is true, then it isn’t like that. Willpower depends heavily on learning the value of activities, which will be much more specific.

I don’t want to go overboard with this analogy, however. It’s certainly possible that some kind of high-level idea of discipline might be able to operate between tasks and contexts. Something like a rule which says, “I always stick to my goals” and then this rule itself becomes more powerful as it is rewarded. Yet, this theory does suggest for me a different way of thinking about improving your self-discipline generally. Once again, doing the real thing seems to matter and bulk training on irrelevant activity seems less effective.

Further Questions

I’m optimistic that further experiments will validate at least some of the ideas in this theory, which seems much more plausible than the resource theory it supersedes. Yet, there are also complexities that need to be sorted out:

- If effort is opportunity cost, why do tasks become more effortful, the longer we persist at them? My own experience suggested this might be due to social factors—you look at the clock, see you’ve been working for an hour and say “that’s enough.” Other motivational researchers argued that motivation itself was a balance between driving and consummatory forces.4 Still, the resource model made the decreasing persistence on tasks an immediate consequence, while this theory makes it more complicated. As go with paradigm shifts, some features become central ones to be explained while others are explained away.

- What explains the two-task experiments, whereby effort on a first task resulted in reduced performance on a second task? The authors suggest that it might be because, in experiments, subjects feel a certain social obligation to perform. Expending effort on the first task would seem to meet that obligation, after which there is less incentive to continue on the second task. Still, it would be nice to see follow-up experiments that look at this more closely.

- Why are so many valuable activities effortful? If effort is a seemingly rational process of assessing opportunity costs, then why are so many useful activities–exercising, studying, working–effortful, while seemingly useless ones are so fun? Evolutionary mismatch might explain some of the discrepancy. In other cases, it may simply be that our motivational hardware is less sensitive to the kinds of long-range benefits of working hard.

- How does this notion of effort tie into other experiences? Physical fatigue, boredom and sleepiness seem related to effort. If this theory holds for mental effort, I would like to know how other experiences we associate with strain interact. Exercise seems to improve cognitive performance, for instance, but being physically exhausted usually makes it harder to sustain on mental tasks after.

Effort is something we all know intimately, yet the precise causes are often mysterious. I’m excited by this theory since it seems to shed light on something that, perhaps because it is so close to our experience, we have a harder time understanding.

Footnotes

- Hockey, G. R. J. (2011). A motivational control theory of cognitive fatigue. In P. L. Ackerman (Ed.), Decade of Behavior/Science Conference. Cognitive fatigue: Multidisciplinary perspectives on current research and future applications (p. 167–187). American Psychological Association.

- Krebs, Ruth M., Carsten N. Boehler, and Marty G. Woldorff. “The influence of reward associations on conflict processing in the Stroop task.” Cognition 117, no. 3 (2010): 341-347.

- Martijn, Carolien, Petra Tenbült, Harald Merckelbach, Ellen Dreezens, and Nanne K. de Vries. “Getting a grip on ourselves: Challenging expectancies about loss of energy after self-control.” Social Cognition 20, no. 6 (2002): 441-460.

- Atkinson, John, David Birch, Introduction to Motivation, Second Edition, (New York, NY: D Van Nostrand Company, 1978), 6

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.