For the past several years, I’ve been trying to get better at research. I’m far from a master, but I’ve learned some strategies that have helped.

I’ve done smaller research-driven essays, from looking into explore-exploit tradeoffs, how aging affects learning and whether speed reading works. I’ve also worked on longer efforts that had me reading quite a bit of material, like I did for my book or my guide on motivation.

Research is an essential part of thinking for yourself. For if you can’t find and understand other people’s arguments, you tend to get stuck either with what your intuition tells you or with the opinion of just one person who managed to catch your attention.

I’m definitely not an expert researcher, but I thought I’d like to share how I go about it, both to clarify my own thinking and to give some help to those who would like to know how to satisfy their curiosity, but aren’t quite sure how to start.

Setting Up Scope and Topic

Unlike learning from a class, research tends to be open-ended. There’s always another book or paper you can read that potentially has an important insight. You’ll rarely reach a stopping point that will tell you you’re done.

But this feature of research efforts also makes them hard to sustain. Our brains like boxes we can check off the to-do list. Open-ended activity often languishes from a lack of completeness.

I recommend deciding how much time you want to commit in advance. I also advise making the end goal to do something with the information, such as writing an essay, rather than have it remain purely mental. Writing an essay or report forces you to organize your thinking, remember key details and ensure you actually understood what you read.

Beginning Research: Looking for Key Works and Keywords

Once you have a scope and topic, the next step is to find the expert vocabulary that matches the topic you’re interested in.

Experts divide up the world in ways that don’t always match how ordinary people think about it. If you want to know what experts think about discipline, then, you’ll quickly find that there’s a difference between self-control, self-regulation, vigilance and grit. In some cases, the words represent fine-grained distinctions in ideas. In other cases, they represent different territories, policed by different groups with different experiments and methodologies.

Wikipedia is usually a good starting point, because it tends to bridge the ordinary language way of talking about phenomena and expert concepts and hypotheses. Type your idea into Wikipedia in plain English, and then note the words and concepts used by experts

With keywords in hand, you can start with trying to identify key works. What are the central texts in this field that other experts all agree are important? Which summarize the field so that you can get a birds-eye view without needing to read too many papers?

Literature Review, Meta-Analysis and Textbooks

Once I’ve narrowed down what the keywords are, and possibly found some central papers or authors that everybody cites on the topic, I usually try to find reviews of the field. In particular, look for:

- Literature reviews, which attempt a qualitative review of all the papers on a particular topic.

- Meta-analyses, which try to aggregate effects from many papers to provide a quantitative answer to a question.

- Textbooks, which being used to teach others tend to present the field in the way experts want new entrants to learn about it.

A good way to start with this is simply to go to Google Scholar and type one of the keywords you identified earlier with the words “review” or “meta-analysis” and see what comes up. If I had previously identified “testing effect” as a concept of note from Wikipedia, I might then type in “testing effect review” or “testing effect meta-analysis.”

For textbooks, I often find it helpful to go to Amazon, enter in the keyword I’m looking for and then limit my search for textbooks. I did this for my most recent research project. I wanted to learn about apprenticeship, so I went through and checked all 47-ish pages of textbooks with “apprenticeship” in the title. After reading about two dozen Kindle previews for the most relevant seeming ones, I read a couple books in full.

Whether you should start with review papers or textbooks depends on the scope of the question you want to ask. Textbooks tend to be good for bigger topics, review papers for more specialized ones, although there is some overlap.

Following the Citation Trails

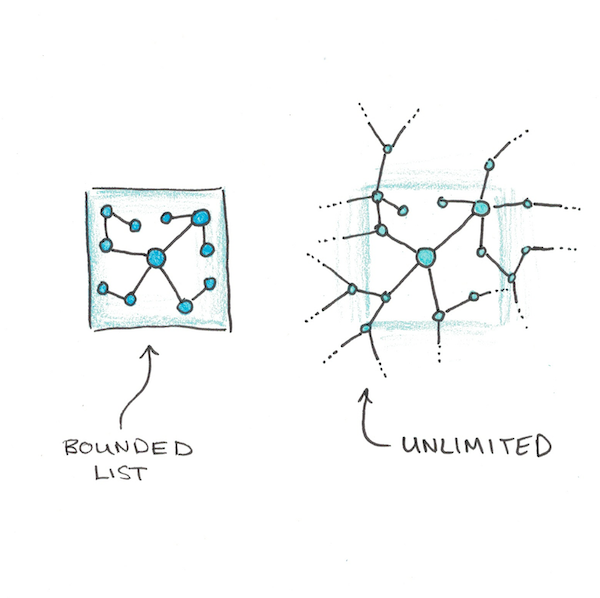

Once you have a foothold within a field, the next step is to follow down citation trails. Since any given paper might cite dozens or even hundreds of other papers, this can easily lead to an exponentially growing reading list. Thus, I usually try to limit myself to a few of the most promising ones to start, unless I hit a dead-end.

When following citations, I look for two factors: frequency and relevance. Works that are cited frequently are more central to a field. If I see the same paper, book or author pop up multiple times, I’ll download a paper even if it doesn’t seem central to my original inquiry. Of course, I’ll also follow-up any reference that seems to directly address the question I care about.

This stage forms the bulk of the time spent. In general it’s better to follow a breadth-first rather than depth-first search, since you can easily spend too much time going down one rabbit hole and miss alternate perspectives. But I don’t follow it slavishly—sometimes you’ll dig into a rich vein of research that answers questions you didn’t even know you had. I ended up adding whole chapters to my book simply because the research was too good to leave as a footnote.

How to Read Research

I once asked Bryan Caplan how he does research, as I admire him as someone to have made me change my mind largely through sheer thoroughness of argument. He said that he reads all of the papers he can, and then when he’s about to write on them, he re-reads them.

Forgetting what you’ve read (or where you’ve read it) is a classic problem in research. Some people have very sophisticated systems for avoiding this, such as Zettlekasten. I don’t find those methods very helpful, but it’s possible that I’m simply inept at them.

Instead, I prefer Caplan’s approach. Read everything you can, including making highlights of sections you think you may need to revisit later. If I finish a book or longer paper, I’ll often make a new document where I’ll pull notes and quotes from my original reading, as well as do my best to summarize what I read from memory. The goal here is partly to practice retrieval and understanding, but also partly to give yourself breadcrumbs so you can find things more easily later.

Some re-reading is probably necessary, though, especially if you’re tackling a big project. My own feeling is that the goal is not to get every fact and detail inside your head, but to have a good map of the area so you know where to look when you need to find it again. With luck, the main findings of the field will stick out, even if you can’t always recall every detail verbatim.

Other Tips and Tactics

Beyond this basic approach, a few other tools have been very helpful:

- Use Sci-Hub to get access to papers. While I’m normally not a big fan of copyright infringement, the current status-quo hardly makes me sympathetic to academic publishers, who have become largely parasitic on scientific enterprise. Alternatively, emailing authors directly often works to get access to papers, but it tends to slow things down as you follow trails of breadcrumbs.

- Use Google Books to hunt down notes within your printed books. I used this a lot when writing my last book. If I wanted to find something in, say, my 900-page Van Gogh biography, I could flip through the index, but it was often easier just to search within the book on Google.

- Map out the key arguments and players. In rare cases, the question you want to ask will have been already settled by science. More typically, you’ll find a wide-variety of different stances argued and defended by different groups. I’ve often found it helpful to map out the key positions and proponents since this is the intellectual terrain where most of the pitched battles of arguments occur.

- Don’t be afraid to take courses first. Reading in a field is like joining midway through a conversation. Except it’s a conversation that’s been happening for hundreds of years. How much you need to back up and understand the prerequisite topics before you can usefully engage with the material depends on the discipline, but it rarely hurts to take some courses that provide a background in the topic.

- Experts are surprisingly willing to talk to you. I was surprised how many busy experts took my calls to discuss their work. K. Anders Ericsson was even nice enough to read through an entire draft of my book and give me feedback on places I mentioned deliberate practice.

One thing I haven’t addressed is evaluating whether a literature itself is trustworthy. I think answering the question of “what do experts think is true?” is hard enough, even without questioning whether it actually is true. So while my abilities here are meager, How to Read a Paper offers a good intro into evaluating research. Still, with the replicability and generalizability problems inherent in many fields, it’s always worth being on-guard that today’s consensus will end up being tomorrow’s quackery.

Do you do research in your work? What strategies and steps would you add to this? I’d love to hear more, especially to improve my own ability to learn.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.