Why is everybody so busy? Nearly a century ago, the economist John Maynard Keynes predicted we’d only work fifteen hours a week. Incomes would grow and so would our free time.

Except that hasn’t happened. Income rose, but we kept working long hours. Why?

One answer is that people like to be busy. This paper argues that people dread idleness and are generally happier when they’re busy than when there’s nothing to do.

Crucially, however, you need a reason to be busy. Without a justification for activity, people choose idleness even though they’d rather be active. If we keep busy, and need a reason in order to do so, it suggests a lot of our busyness may be self-imposed.

Reasons for Our Collective Busyness

We feel too busy, but there’s evidence that at least some of that is unnecessary. What explains the gap?

I have a few theories:

- Busyness as signaling. Busy people are important. Complaints about busyness are like complaints about paying too much in taxes—something that allows you to subtly communicate your status.

- Busyness as dodging commitment. Claiming busyness is a socially acceptable way to decline social obligations. “I wish I could, but I’m too busy,” is more polite than, “No, your nephew’s piano recital doesn’t interest me very much.”

- Busyness as self-deception. When you work on things, your goal is always to move toward a state of having less stuff left to do. Since less outstanding tasks is better within the context of your goal, you may incorrectly extend that to assume that having no outstanding tasks in life is ideal.

Another plausible explanation is that busyness exists on a spectrum. We may abhor idleness, but being too busy stresses us out. There’s a sweet spot in the middle that suits us, and fine-tuning that amount is tricky.

Finding the Busyness Sweet Spot

I feel like I’m happiest when I’m ever-so-slightly too busy. Not so busy that I feel overwhelmed, but enough to feel like there isn’t quite enough time to get everything done.

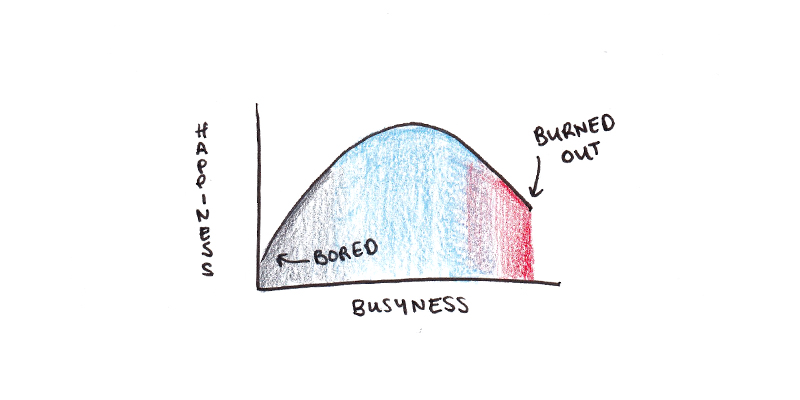

I think for most people, there’s a scale from utterly bored to burned out, with the ideal level of busyness lying somewhere in between:

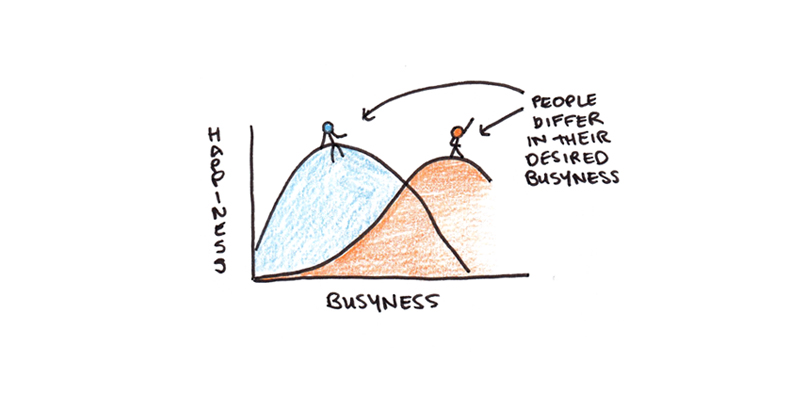

Observationally, some people seem happier when closer to the “relaxed” end of the spectrum. In contrast, others seem to require more activity to be happy. This difference may even have a biological basis. Different people seem to have their dials set differently for the optimal level of stimulation.

Additionally, you might find yourself outside of this spectrum temporarily. It’s always possible to take on more commitments than you realize and feel busier than is ideal. It’s also possible to have few immediate outlets for activity and feel bored and directionless in life.

There seem to be two different settings in the busyness-happiness calculation: first, what your ideal set point is, and second, whether your temporary situation is above or below this optimal set point.

What are Good Reasons to Be Busy?

As the authors of the aforementioned study note: we need a reason to be busy. Even if we’d prefer busyness, we don’t just do things just to do them.

The quality of that reason makes a big difference. A very compelling reason can lead to overcommitment if you’re not careful. But if you don’t have a good reason to be active, it can be hard to find enough to do to get to the optimal level. I tend to vacillate between having an exciting project (that also occasionally stresses me out) and having no project and feeling aimless.

Finding a good project to keep yourself busy can be tricky. Just wanting to fill time doesn’t seem to be a good enough excuse.

Goal-setting and planning are vital because they’re the tools we use to find motivating activities. Making concrete improvements to your life may be secondary to the well-being boost of having a reason to be optimally busy.

Do You Really Have Too Little Time?

Strictly speaking, we all have the same amount of time each day. Nobody has more or less. What feels like a lack of time is, more accurately, a conflict between priorities.

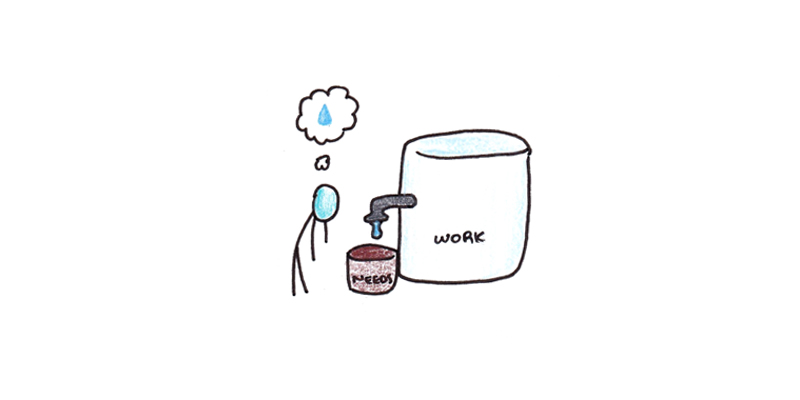

One problematic form of busyness occurs when your activity has low intrinsic enjoyment. If you’re forced to work long hours at a job you hate, then you need to somehow meet your psychological needs in the little time you have left. This can be tricky.

Expectations are another issue. If you intend to work full-time, stay in shape, spend quality time with your kids, and keep up with friends and hobbies, you may find there’s not enough time to do all of those to your desired standard. The result is frustration, even if the hours in the day haven’t actually shrunk.

All of these can make the experience of excessive busyness unpleasant, even if you’re still working with the same twenty-four hours per day as everyone else.

Unconventional Strategies for Optimizing Busyness

There are a few different levers we can pull to optimize the busyness in our lives:

1. Adjust Your Expectations

As I just mentioned, expecting too much from yourself (or too little) is a recipe for stress. Sometimes the key is to take a step back and ask yourself what’s actually realistic. If you’re already at the productivity frontier, perhaps you need to cut yourself some slack.

We rarely feel like we ought to be busier. Instead, this manifests as feeling like we don’t have anything meaningful to work toward. Setting compelling goals can raise expectations and force you to engage in life in ways that make you happier.

2. Find More Satisfying Work, Friends and Hobbies

If you spend a lot of time doing things that don’t satisfy you psychologically, you can feel like you have too little time.

Work can be a major culprit. If you feel like you’re not satisfied with your job, Cal Newport’s book remains my favorite on career satisfaction.

Still, friends and leisure pursuits can also be drains. Do you feel overwhelmingly busy but somehow spend hours binging Netflix or scrolling on your phone each night? Perhaps the problem isn’t a lack of time but a lack of activities that actually meet your needs.

3. Create More Filters and Constraints

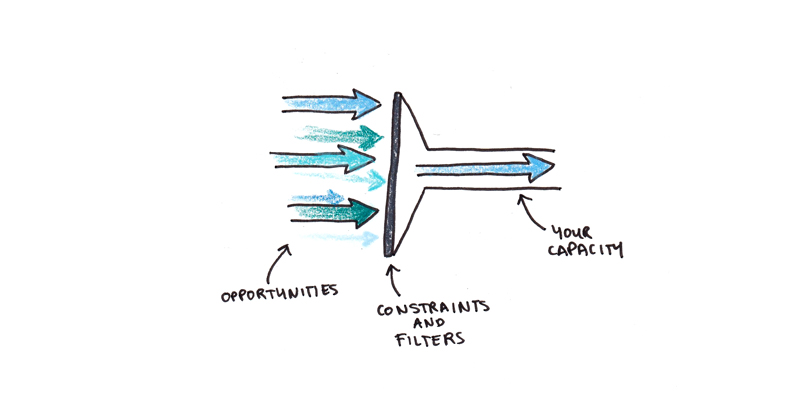

Temporarily feeling too busy or bored is often a problem of balancing new opportunities and existing commitments. When the flow of upcoming opportunities is a trickle, we feel restless and bored. When the flow is a torrent, we feel overwhelmed.

Better managing this flow can solve some of the busyness problem. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, tighten up on your constraints so more new opportunities default to “no.” If you’re feeling idle, relax those constraints and start saying “yes” to more speculative opportunities.

Different sources of obligations may need to be managed differently. For instance, while I almost always say no to speaking requests, I usually agree to podcast interviews because the time commitment is much smaller than a prepared speech. Often when we’re overly busy, it’s because a specific source of obligations isn’t being managed correctly.

These strategies tend to be more effective over longer time horizons. Consistently applying the principles above can help you work toward a life of optimal busyness months and years from now. Still, there are fewer remedies for feeling too busy right now. Ultimately, however, finding the right balance of engaging, meaningful activity is one of the best ways we can live better.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.