The biggest sin a book can commit is to be boring. A wrong book that makes you think is still worth the journey. With this in mind, I read French philosopher Bruno Latour’s We Have Never Been Modern during a recent vacation (you know, for some light summer reading). I found the book fascinating, even if I’m not quite sure I agree with it.

In this book, Latour grapples with our very conception of modernity.

What does it mean to live in a modern society? How are we different from our ancestors and all the supposedly “pre-modern” people around the world today?

Despite being published thirty years ago, We Have Never Been Modern feels timely. Media is fractured, information is exploding, and we’re cajoled to “follow the science” even though few have the skills to figure out what the science actually says. Are we living in a hypermodern time our tribal brains can’t comprehend? Or are we in a post-modern, post-truth society where everything is relative and anything is permitted?

Latour argues that our self-conception is a myth. We’re not living in a post-modern age, he argues, because modernity has never begun.

What Does It Mean to Be Modern?

One way to argue that we’re modern is to simply look outside. We fly in planes, splice genes, and talk to people on the other side of the planet instantaneously. In this sense, we’re definitely different from medieval peasants or hunter-gatherers.

But modernity has often implied more than just technology. Pre-modern cultures have beliefs; we moderns have science. Those other cultures freely blend objective facts with socially useful superstitions. We moderns aren’t so confused.

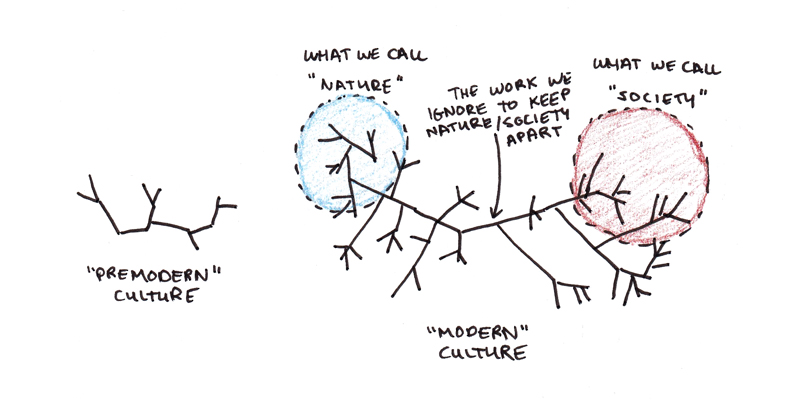

Instead, Latour argues that we never actually left the kind of society studied by anthropologists. An analysis of modern culture should be, in principle, just as possible with modern society as it is for tribes in the jungle. The reason we find it difficult, he argues, is that modernity is based on a paradoxical self-understanding, which he calls the modern constitution.

The Modern Constitution

A constitution sets the framework for how a government functions. Likewise, we can imagine our own culture’s unwritten constitution as defining the separation of powers, obligations and tacit requirements needed to make our world work.

This modern constitution, Latour argues, is based on a series of self-supporting (and self-contradicting) principles.

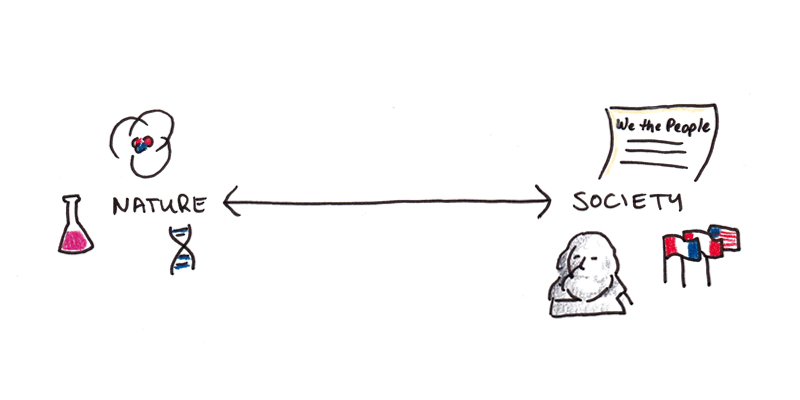

The first principle is the presumed separation between Nature and Society. Science allows us to separate the facts which exist independently of what people think of them. In contrast, democracy and liberalism allow us to construct the interpersonal order however we wish.

Latour traces this division to Robert Boyle and Thomas Hobbes.

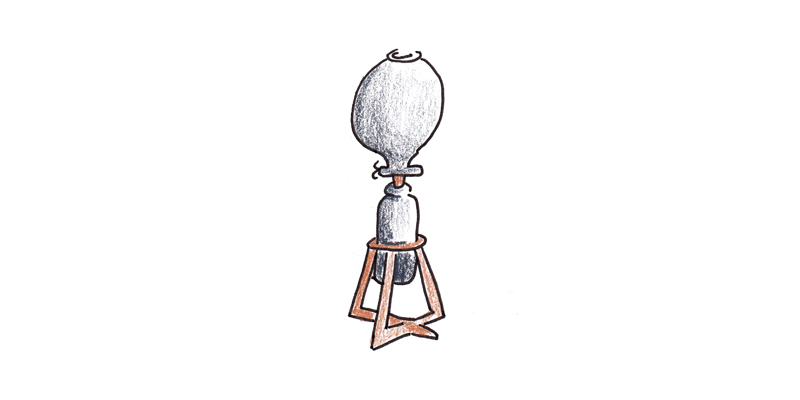

Boyle created an air pump that became a model for scientific investigation. For the first time, instruments witnessed by bystanders could create incontestable facts. This created a foundation for an “objective” reality separate from human subjectivity.

Hobbes, in contrast, imagined a purely constructed social order. In his Leviathan, he argued that citizens would bestow all authority to a single ruler to escape anarchy. Fealty to a king was hardly novel. But what was different was the reason for fealty. Hobbes imagined a political order that was grounded in a social contract, not appeals to God or nature.

Support for absolutist monarchy may have waned, but the idea that society is whatever we agree it should be is an assumption deeply rooted in the modern psyche.

Modernity, Latour asserts, is the product of their stalemated debate. Boyle wanted facts that would speak for themselves. Hobbes imagined a self-generated society independent from material circumstance. Nature and Society get pulled apart.

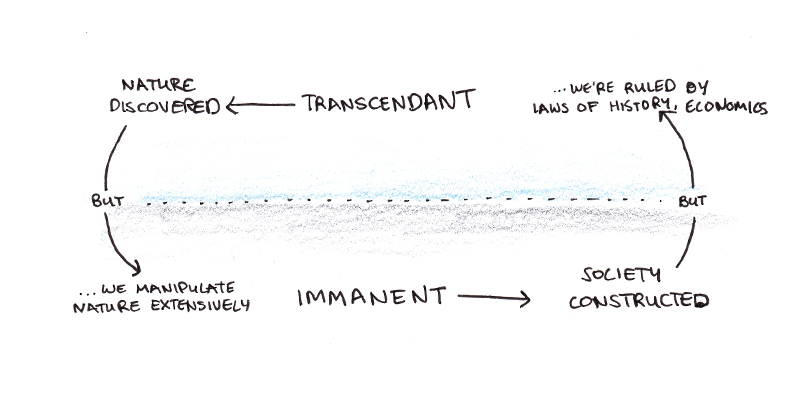

This first distinction leads to others. Nature is transcendent—we do not create it, only discover it. The air pump speaks the truth about the world we cannot argue over. Ignoring, of course, the technical difficulties needed to get it to work, the observers needed to interpret it, and the network of scientific communications to disseminate its universal findings.

Society, in contrast is immanent, it is a phenomenon inherent to humanity and independent of nature. Following Hobbes’ model, Latour argues, we design our political life entirely from scratch. If Nature is wholly outside our grasp, Society is entirely within it. Indeed, for something to be social, it is defined as something we construct by shared agreement.

Of course, these distinctions aren’t stable. Nature is transcendent, but we increasingly gain the power to modify, control and shape it to our desires. Society is immanent, but we increasingly discover iron laws of politics and economics that seem to prevent us from freely choosing its shape.

Latour argues that this absolute separation of transcendent Nature and immanent Society is self-contradictory. It can only be maintained because of an additional, harder-to-see separation in modern society.

Purification and Mediation

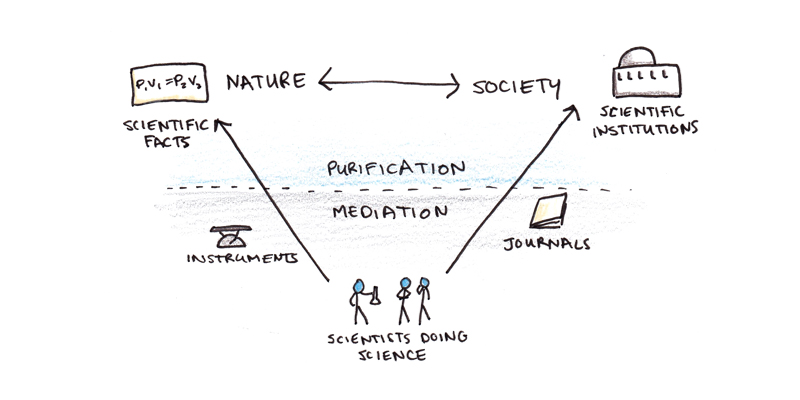

Latour argues that our entire modern constitution is propped up by a further distinction between purification and mediation.

The world is full of quasi-objects—stubborn phenomena that are neither purely “objective” nor purely “conventional” but awkwardly straddle the line.

Consider a scientific journal article. Nearly everyone recognizes that social processes as well as natural ones constrain its creation—a paper might get ignored because it goes against the favored view of the most eminent theorist in the field. Is that a matter of scientific fact or social process? Neither—it’s somewhere in-between.

Purification is the process of separating nature from society. Separating “science” from the social world of the scientists needed to create it, as well as “democracy” from the various material factors that constrain it.

Mediation is the glue that holds the poles of Nature and Society together. Its the voting machine that tabulates the public will, the journal article that summarizes scientific fact. These factors tend to be ignored in modern discourse, or when they are focused on, it is merely on their ability to transmit objective facts or social agreement, rather than acting as complex agents in their own right.

Consider Boyle’s air pump: it can create a vacuum, something Aristotle thought logically impossible. But it also leaks occasionally. And it’s hard to interpret. How do we know that there’s nothing in the empty chamber? Indeed, mercury, which Boyle used in the experiment, has an associated vapor pressure, so in this case the “purely objective fact” of the vacuum is actually false!

The social process of purification is to tidy up all of this messy work of imperfect instrumentation, theoretical nitpicking, and arguments between experts to leave us with a pure product: a scientific fact. A fact is an entity that erases its own construction and thus is no longer up for debate.

Likewise, Society has similar processes we use to squeeze the ambiguity out of the material considerations needed in democracy—such as enforcing human rights or ensuring fair elections.

Unfortunately, because our “modern constitution” can only deal with pure processes, these hybrid, quasi-objects belonging to neither Nature nor Society must be ignored or treated as empty intermediaries, i.e., they channel a pure essence without contributing anything to the end result.

Latour argues that the dirty work performed by these unacknowledged hybrids is what runs our societies. But because of our commitments to the constitution, we rarely recognize it as such.

When we reunite the work of purification and mediation, we see that the principle difference between our society and earlier ones is scale, not kind. We have created a vastly more complicated network linking all the elements of our science and culture. Still, we have not created a distinct kind of culture that can see “objective reality.”

What Should We Make of This?

As I said from the outset, I find Latour’s arguments interesting, even if I’m not entirely persuaded.

I had similar difficulty with Latour’s take on science in Laboratory Life. On the one hand, he did a good job explaining how all the sociological factors that affect any human endeavor also impact science: Researchers fight for credit. Scientists accept or ignore evidence based on tacit considerations of others’ work. What “counts” as a finding is itself a negotiated stance, with different researchers pushing for different levels of evidence or methodological rigor. All of which is pretty banal and obvious.

Yet, it seemed that Latour extended this argument to say that the fact that sociological factors influence science implies that science is arbitrary. That, with a different set of starting assumptions and political dynamics, we might end up with a totally different kind of science.

This seems crazy to me. Whatever reality is, it certainly constrains the outcomes of our theories and facts at least as much as sociological explanations do.

But maybe Latour isn’t actually saying that? Again, I find it hard to interpret his views here on a continuum from “science is shaped by human concerns in the boring and obvious ways you expect” to “science is totally arbitrary.”

Perhaps I’m finding it difficult to understand Latour’s views here, in part because I’m still committed to the dualism between Nature and Society he argues against. I think the only two options are “science is real” and “science is made up” because I’m still trying to see things only in terms of pure products of Nature or Society, and pretending all the hybrid elements needed to get both to work don’t exist.

Regardless of whether Latour is right or crazy wrong, I’m sure I’ll keep thinking about it. By that standard, We Have Never Been Modern is an excellent book.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.