In a recent essay, I argued that most people are trying to do too much. In the attempt to do everything that interests them, they end up making little progress on anything.

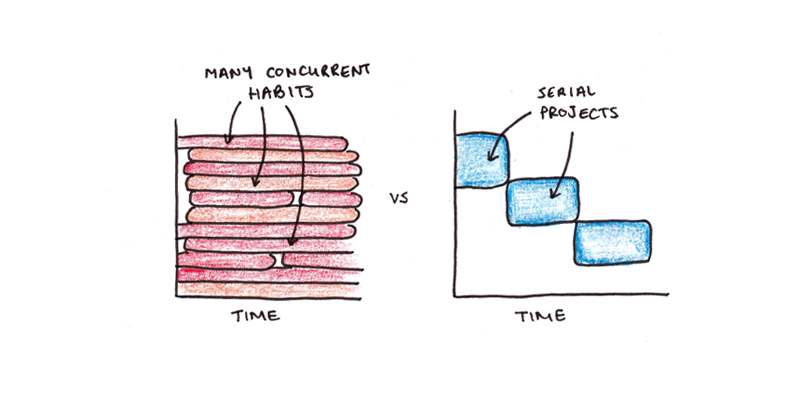

One reader noted a problem. Doesn’t this view of having a few serial projects contradict the idea of building good habits? Isn’t it the idea to make slow and steady progress on all your goals rather than work in intensive bursts?

This tension has come up before. After my book came out, I received an angry rant that argued that the intense projects I documented in Ultralearning were wholly opposed to the habit-centric philosophy of my friend and foreword author, James Clear, as stated in Atomic Habits.

So which is it: slow and steady habits or intensive projects?

As is my usual style, I think the answer is both. Habits and projects are both useful tools. They tackle different kinds of problems and have different limitations. Whether a habit or project is the appropriate tool depends on the nature of the goal you are trying to achieve.

The Habit-Building Philosophy

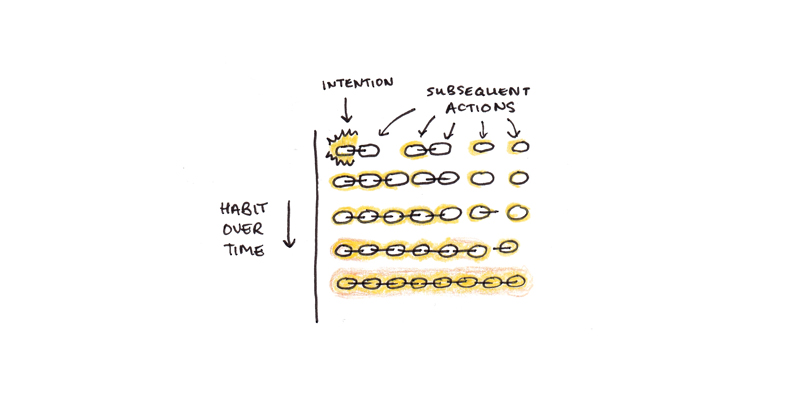

Habit building, the process by which behavior becomes increasingly automatic, has a long history.

William James, the father of scientific psychology, made habits a centerpiece in his magnum opus: The Principles of Psychology. Habit, he argued, is the fundamental principle of the mind. Behaviors link together until they become automatic and fall out of awareness entirely.

For more than a century, automaticity has remained a conspicuous theme in our understanding of the mind. Early behaviorists defined the shaping of stimulus and response as the basis of human action. More contemporary theories of skill acquisition focus on the shift from controlled, effortful processing to automatic behavior as a central feature of mental life.

The philosophy of habit-building takes these observations and relates them to our goals. If effort is the primary barrier to action, and repeated, rewarded actions become more automatic, then building better habits is an essential tool.

Habits VS Projects

There are a few ingredients needed to make habits work well:

- The behavior can become routine. If it requires complex thinking or planning, it is not a habit, by definition. Sitting down to write each morning can become a habit; the act of writing itself cannot.

- The behavior must be rewarding and enjoyable. In my essay on the meta-stability of habits, I point out that many behaviors we want to turn into habits aren’t enjoyable on their own. This means that while they can become easier and more automatic, they will never entirely transform into mindless routines.

- The goal requires patience more than intensity. Many goals face diminishing returns—the first hour of weekly exercise matters more than the fifteenth. Not all goals are like this. Getting a new job, launching a start-up or passing an exam have thresholds. Under a certain limit, the return on effort is zero.

None of these mean that complicated, difficult or intense goals can’t benefit from habits. If I’m writing a book, I might benefit from a routine of sitting down to write every day. The habit-based tools can make writing more automatic, even though the goal itself isn’t maximally habit-friendly.

However, and this is important, having a habit won’t be enough. Book-writing is not as simple as churning out a page a day. Writing a book depends not merely on typing words, but editing, getting feedback, doing research, and obsessing a little too much about a topic that you think is important. Many terrible books have been written under the misconception that hitting a daily word count is the hardest part of writing.

Writing a book, then, is a project. It requires mental overhead to manage the complexity, as well as focus to push through frustration. It requires thoughtful, planned action that can never be made fully automatic.

Projects, particularly the philosophy of having a few, serial efforts, can be used to handle these difficulties.

Habits AND Projects

As tools, habits and projects coexist nicely. If you have a goal to write a book, the daily rituals involved in writing can be routinized. But you must recognize that the deep thinking and planning needed to write well can’t be automated. Good authors learn to combine both. They regularly set aside time to write. And they don’t kid themselves that writing a book is effortless, something they can churn out without much thought.

Habits are plenty for some goals, but others will need projects. I might set a goal of exercising daily—if I stick to it for long enough, it can eventually become an automatic behavior. But if I decide to run a marathon for the first time, it will likely require more than just my daily jog. If I want to win the marathon, I will need a lot more than just a habit.

The Effort Continuum

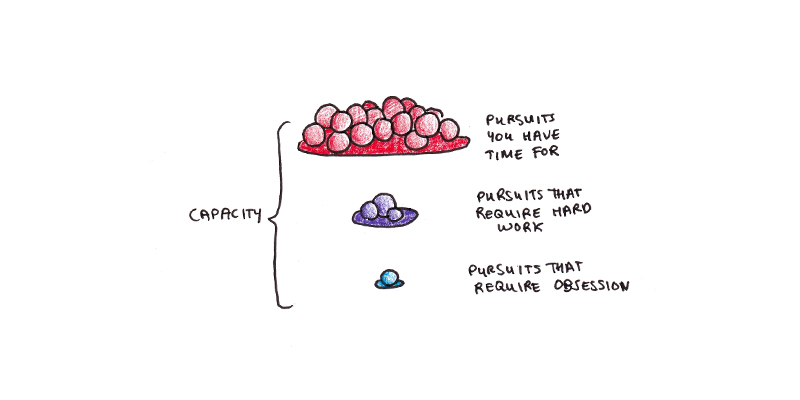

There are three different resources that you invest in a pursuit: time, effort, and attention.

Time is the most obvious—you only have so many hours in the day. Thus, even if it doesn’t require much effort or thinking, a time-intensive habit may bump against other pursuits. Even if you could use every minute of the day productively, you might still not have enough time to do everything you’d like to.

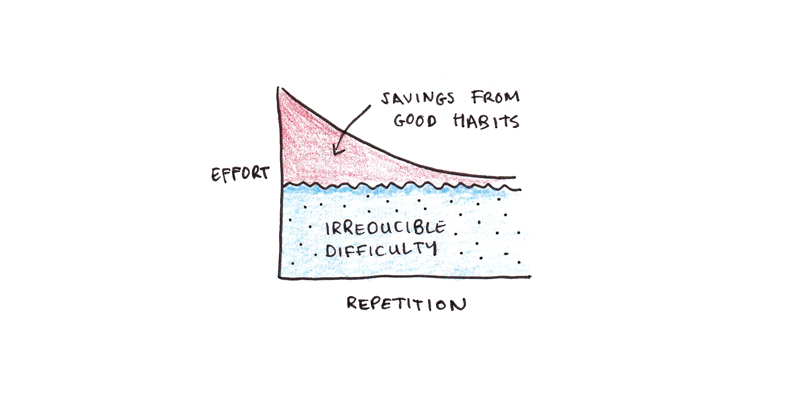

Effort is next. With careful conditioning, habits can become less effortful, but the effort rarely goes down to zero. This non-zero effort has two effects. First, when combined with the inevitable jostles of life, it can lead to a need to rebuild old habits semi-regularly. Second, it means that even if you can conceivably fit all of your desired habits into your schedule, you may not have the effort available to do them all.

Attention is perhaps the most constrained of all. If a project requires planning, reflection and obsession to reach completion, you’re probably limited to at most one or two efforts at a time. Anything more is going to reduce your performance sharply.

The number of pursuits you can take on at once depends on where they fit on this continuum. Habit-building can shrink the effort and attention required, although rarely to zero.

The aim should be, with every pursuit, to try to make the regular investments of effort required more habitual. However, pursuits have a degree of irreducible difficulty that requires focus. For the new author, writing a book would probably benefit from a daily writing habit. But this doesn’t imply that, habit installed, she ought to also learn French, practice guitar, start a business and take on a new role at work at the same time.

My Experience with Projects and Habits

I’ve spent most of my adult life pursuing a combination of projects and better habits. I’ve tried nearly every strategy out there. While this hardly reaches the rigor of a controlled experiment, I’d like to reflect on my experiences.

Exercise tends to work well as a habit. Although the time remains constant and the effort rarely goes to zero (fun sports are often an exception), the attention needed really can go to zero. Exercise enough, and you can think about other projects while working out.

Exercise is also the paradigmatic goal that requires patience over intensity. You can’t stockpile fitness, and being active throughout your life has enormous downstream benefits.

Writing articles works well as a habit, provided my goal is consistency. I’ve written over 1500 articles during the last decade and a half. That’s probably two million words of published material. Few could argue that I don’t have a solid writing habit.

Yet this habit doesn’t always drive improvement. Whenever I want to make a leap in my writing to something new, I have to put in a ton of effort. Often, the habit works against improvement, rather than for it, as I have such ingrained writing behaviors that they are difficult to dislodge.

Working on books, courses, or ultralearning efforts are all intensive projects. They’re areas where few results came from the mindless repetition of easy work. Yet, even here, habits often undergird my efforts. One of my first steps in the MIT Challenge, for instance, was establishing a studying routine. It was far from effortless, but consistency made it doable.

This blending of habits and projects has been a theme throughout my life. It’s part of the reason I get perplexed when I see the two approaches contrasted—as if it were one or the other. But if you understand how each works, and their respective limitations, you can make more progress than dogmatically sticking to either.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.