Setting goals can transform your life. Goals can help you get in shape, improve your finances, learn a new language, or finally launch that business.

But goal-setting can also leave you miserable. Burnout, stress and disillusionment are high on the list of potential side effects.

The crucial difference between success and burnout often comes down to how your goals are designed. Done wisely, setting goals can be a positive experience—not just successful, but life-affirming. Here are seven research-based suggestions to help you design better ones.

1. Aim for Hard, but Believable

For over four decades, psychologist Edwin Locke has been central in research on goal-setting. His research has three consistent findings:

- Setting goals improves performance.

- Hard goals improve performance more than easy ones.

- Specific targets work better than simply trying to “do your best.”

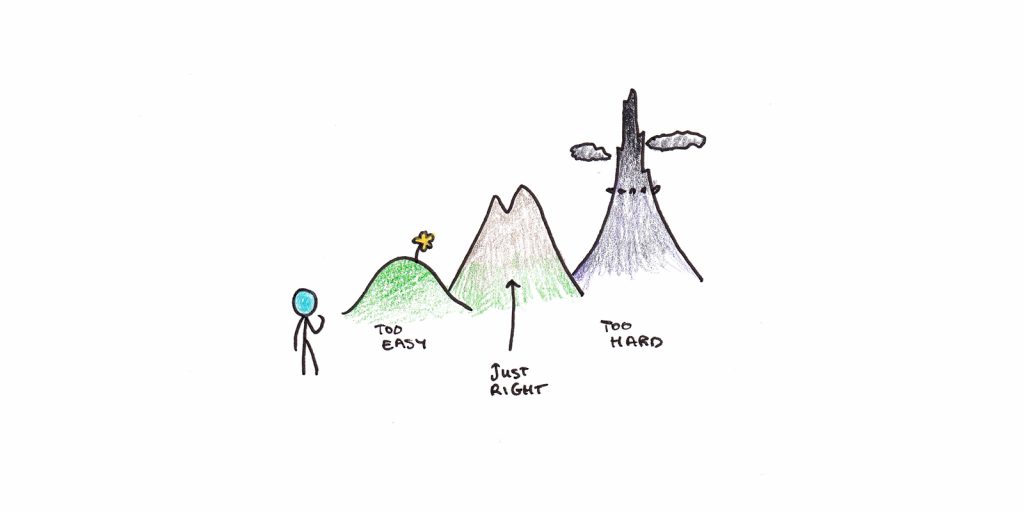

Early research on goal-setting found that there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between difficulty and performance.1 This means that easy goals lead to weak efforts, but so do goals that are too hard. The key factor here seems to be that goals need to be challenging, but also believable to be effective. If you don’t think you can actually reach a goal, you won’t.

Thus the best goals to set are those that demand effort from you, but you’re confident you can achieve if you put in the effort.

2. Use the 80% Rule

How do we build motivation to pursue our goals? Psychologist Albert Bandura developed the concept of self-efficacy to explain why some people eagerly face challenges while others shrink. If you don’t feel you’ll be successful, why bother?

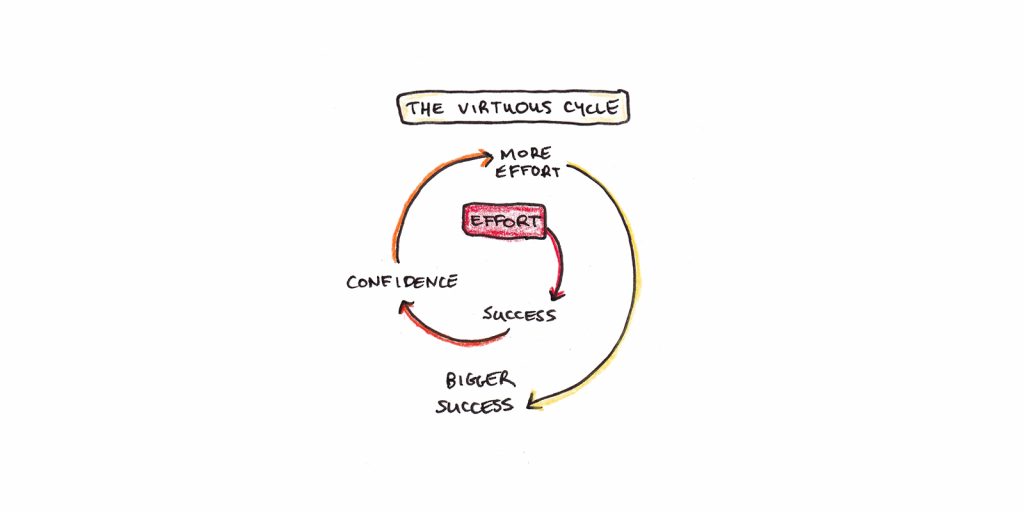

The danger is that self-efficacy can create either a vicious or a virtuous cycle. If you don’t feel you’ll be successful, you don’t put effort into your goals. This leads to failure and seemingly confirms your inability. The reverse is also true: you can pick successful goals, achieve them and steadily boost your confidence.

One way to build confidence is the 80% rule. Psychologist Barak Rosenshine, in his review of successful teaching, found that this was approximately the success rate students should experience while in school. Too much success, and you’re likely not picking hard enough goals. Too little, and you can fall into the confidence trap.

One way to calibrate this is to set smaller goals (think 30 days) and track your success rate. If you’re under 80%, try setting a more achievable target. If you’re over 80%, try something a little more ambitious.

3. Deadlines Are Poison for Creative Problem-Solving

A significant exception to the power of specific, challenging goals involves creative problem-solving. In tasks that require complex thinking, such as learning, problem-solving or creative work, goal-setting can backfire.

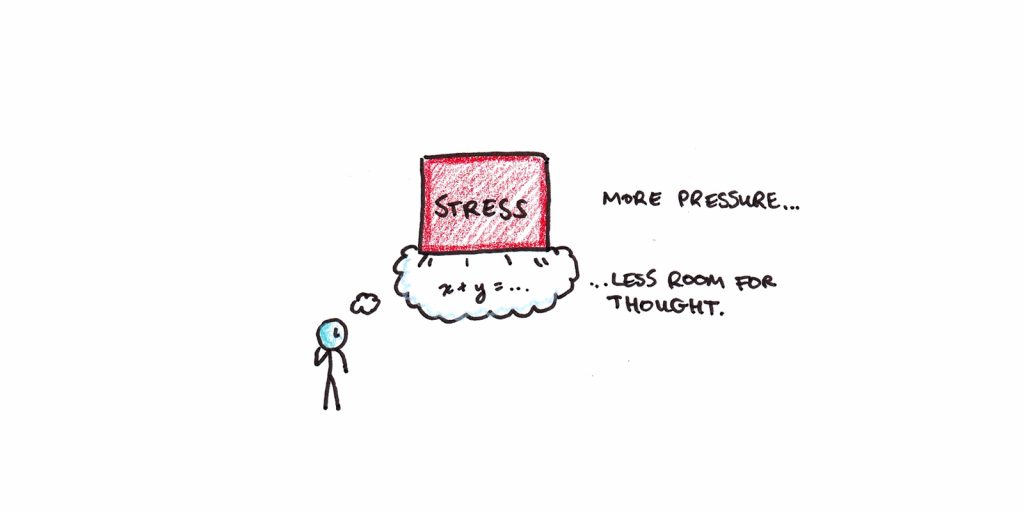

Why is this? It’s because these activities require the full use of your working memory. Working memory is a psychological concept that corresponds roughly to mental bandwidth. It’s been known for several decades that the amount of things we can keep in mind at one time is limited—and often less than we think.

A stressful deadline to come up with a creative solution can hurt. The goal itself occupies so much space in your working memory that you have little left to try out new possible solutions. In these cases, you’re better off in a relaxed state with minimal distractions.

Of course, here we have a conflict. Goal-setting works by marshaling motivation and energy to reach a goal. Without goals, we often fail to put in the effort needed to achieve. However, if we are thinking about the goal while we’re working, we lose that mental bandwidth to develop creative solutions. How do we fix this?

One way is to set goals to work on a creative problem for a chunk of time without interruption or expectation of results. This allows you to focus on the task and gives your mind more space to think of solutions.

4. Visualize Failure

A common suggestion for goal-setting is to visualize success. But visualizing failure might work even better.

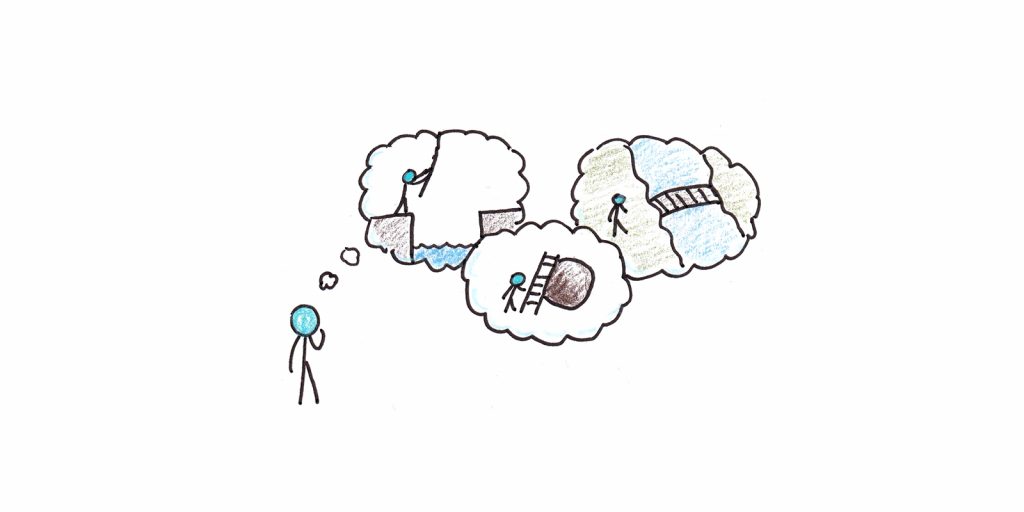

Psychologist Peter Gollwitzer suggests a key ingredient to the success of your goals is what he calls implementation intentions. These are when you visualize difficulties that might come up in pursuing your goal and decide in advance how you will handle them.

Many goals get derailed by events that are unexpected but not unimaginable. You get sick two weeks into an exercise program. Your exam gets rescheduled. You were ready to start your business, but the permits are delayed.

Imagining obstacles in advance and deciding your response can make those responses more effective when the time comes. Since your motivation is usually highest when setting the goal, this planning can keep you from abandoning your goal when things get difficult.

5. Keep it to Yourself (At Least to Start)

Should you tell other people about your goals? Surprisingly the answer is sometimes no.

In addition to implementation intentions, Peter Gollwitzer also studied the effects of telling people about the goals you want to achieve. Interestingly, his research found that telling people about your goals can substitute for actually taking action. Why is this?

Gollwitzer explains the results in terms of his theory of symbolic self-completion. According to this theory, we all want to maintain our image in the eyes of others. To do that, we display signals of our self-identity. Announcing our goals can make us feel like we have sent that signal, and our motivation to achieve the actual goal can go down.

This suggests we should focus first on taking action, not talking about it.

6. Break it Down and Make Yourself Accountable

Why do we procrastinate? The common perception is that procrastination is caused by perfectionism. People who need to do everything perfectly waste time getting started.

Except research doesn’t bear this out. In a comprehensive review, psychologist Piers Steel found perfectionism didn’t predict procrastination. What did? Unpleasant tasks and impulsive personalities.

One difficulty with setting goals is that our motivational hardwiring doesn’t cope well with the future. When a deadline is far off, and the immediate work isn’t always fun, we’re likely to slack. This persists until shortly before the deadline when the fear of failure spurs us to action. Unfortunately, as we discussed in point 3, these last-minute efforts aren’t ideal for complex work.

The key is to break down your goals into smaller, daily actions. If you know what needs to be done today, you’re in a much better position to act on it.

It is even better is if you can create a compelling incentive to stick to the daily plan. A powerful tool for overcoming procrastination is precommitment. Telling a friend or spouse that you’ll give them money for each day you miss your plan is a surefire strategy to stay committed.

Less extreme solutions can also include following a “don’t break the chain” strategy. Once you’ve set your daily plan, keep a tally of how many days in a row you’ve followed it. The goal is not to miss a day. If you do, reset your tally and start over.

For goals that don’t break down into simple, daily habits, you can still focus on daily actions. Break the goal into smaller milestones that have short-term deadlines. The closer you can move your goals to the present, the more successfully they will guide your behavior.

7. Set Goals You Want to Achieve (Not Just Those You Feel You Should)

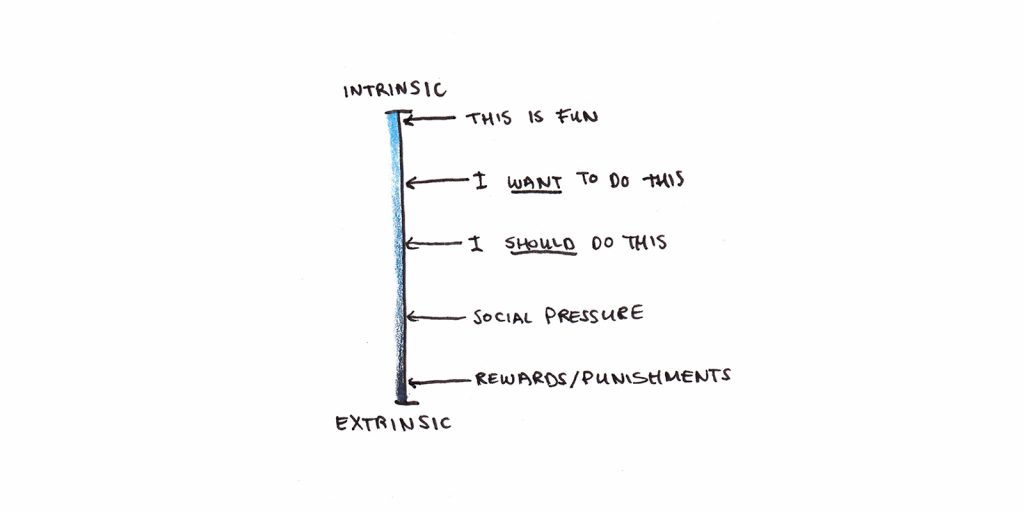

Much of the stress and disillusionment people experience with goals comes from setting ones that aren’t truly their own. When we work on the goals of other people, goals we feel pressure to achieve but don’t actually want, the result is often misery.

Self-determination theory was developed by psychologists Edward Ryan and Richard Deci. They found that external incentives, such as paying someone to complete an otherwise interesting puzzle, could crowd out internal motivation. People would play the puzzle while being paid to, but they would play less when the rewards stopped.

They argue that many of the goals we pursue are only partially our own. We chase them because we feel we should, but they are somewhat “alien” to our deeper selves. Since these goals mainly just fulfill social expectations, they are harder to motivate ourselves toward consistently.

I suspect that the prevalence of these goals is why many have soured on goal-setting altogether. They have too many goals that aren’t truly their own. As a result, they are poorly motivated to achieve them, often fail to put in adequate effort, and experience stress and burnout.

For goal-setting to be life-affirming, the goals pursued have to feel deeply meaningful to you. Getting in touch with what you really want out of life, and separating out the things you merely think you “should” want, is perhaps the most essential part of goal-setting. A good life isn’t measured by the sum of your achievements, but by the meaning you attach to them. Choose wisely.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.