It’s been almost a year since I started my current research project. My initial starting point was the intriguing, if somewhat pessimistic, research on learning transfer. However, crawling through citations has gotten me to some of the more interesting science on how people think the mind works.

Having now read over 70 books and 250 papers, a picture is emerging of how it all connects. My views have definitely evolved since the project started, which is probably a good thing—if reading books only reconfirmed everything you already knew, there’d be no point in reading them.

Here are a few picks from my most recent batch:

1. Apprentice to Genius by Robert Kanigel

How is elite level science produced? Kanigel offers a fascinating portrait of one scientific dynasty, working at Johns Hopkins, that has produced Nobel and Lasker prize-winning scientists.

I found this portrait fascinating because it suggests to me that there is a hidden, tacit knowledge involved in producing elite level work. While the scientific foundations learned in school are clearly important, this crucial knowledge is still transmitted mainly via the master-apprentice relationship.

My leading explanation for the effect Kanigel observes is that, through a lifetime of experience, elite scientists build an incredible skill for identifying fruitful scientific opportunities. Since they can’t personally pursue all of them, they attract intelligent students and assign these problems to them. By achieving success, the novices eventually adopt the same pattern recognition abilities of the masters and hone their scientific “style.”

This book illustrates the incredible importance of mentors and guidance in doing elite level work. It also indicates why there is so much inequality in output. The knowledge learned in school is necessary—but rarely sufficient—to perform at the highest levels. Those who lack access to these mentor networks are often excluded from doing groundbreaking science.

2. A Cognitive Approach to Language Learning by Peter Skehan

Language learning is a topic where I have a lot more hands-on experience than theoretical backing. Having learned several languages to middling proficiency, I have lots of intuitions about what works best, but fewer rigorous experiments.

Skehan’s book both shed light on some experiences I have had while learning a language and challenged some of my preconceptions.

Skehan sketches language learning as a process of acquiring vocabulary and grammar while bound by the constraints of a limited working-memory system. A few of his key findings:

- Memory plays a much larger role than most realize in language learning. Linguists are obsessed with how we acquire the rules and usage of a language. It seems like people not only memorize words but entire “chunks” of phrases to reduce processing burdens.

- In speaking, we are overwhelmingly focused on getting our point across. This aids our communication goals, but can conflict with learning more complex and correct forms of the language, since less capacity is available to focus on those aspects.

- Speed, correctness, and complexity must all trade-off under such a system. Good language learning involves a mix of practice opportunities that give chances to strengthen each aspect.

While I wouldn’t change my language learning strategy at the early stage, Skehan’s work shows why just having conversations eventually stalls further progress. You need practice opportunities that stretch you because speaking becomes easy long before you become really good.

3. The Sweet Spot by Paul Bloom

Suffering is part of a meaningful life. I enjoyed this book because it pushes back against the hedonic emphasis of so much of positive psychology.

Meaningfulness is not all that related to momentary happiness. Self-chosen challenges are an essential part of the good life. This is obvious to any student of philosophy. Still, it seems to have been largely ignored by social psychology interested in measuring positive well-being.

Bloom’s book surveys the research landscape, which, to put it mildly, is mixed and confusing. Thus, I found it provided an interesting window into how science has tried to tackle the problem of meaning, yet I was left with the impression that we haven’t made much progress.

4. Productive Thinking by Max Wertheimer

Max Wertheimer was the founder of gestalt psychology. Productive Thinking, published posthumously, is one of his most important works. Productive thinking refers to “creative” thinking rather than mere habit or routine thinking.

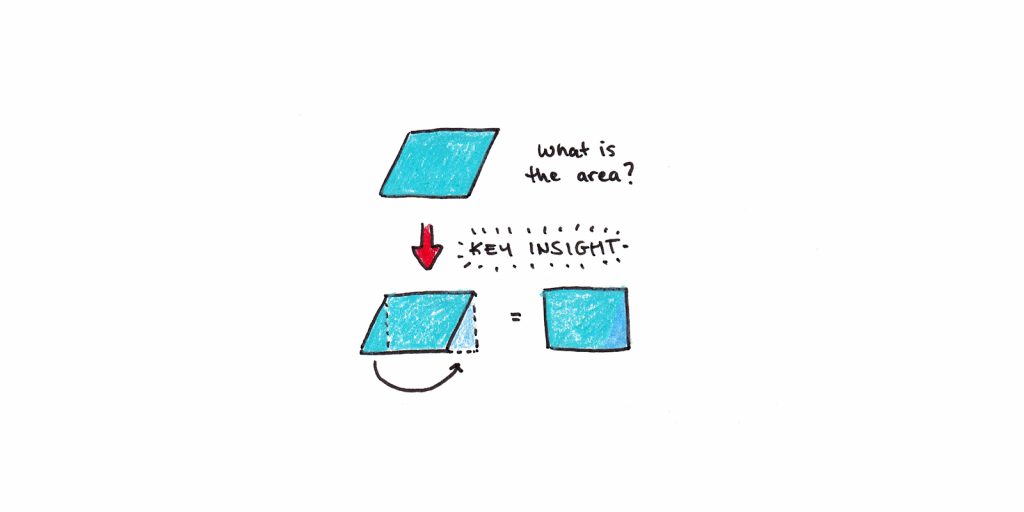

Wertheimer explores a number of intriguing puzzles. My favorite is the process people use while trying to figure out how to solve for the area of a parallelogram. The abstract insight people manage to draw from this determines, in large part, what other types of problems they can solve.

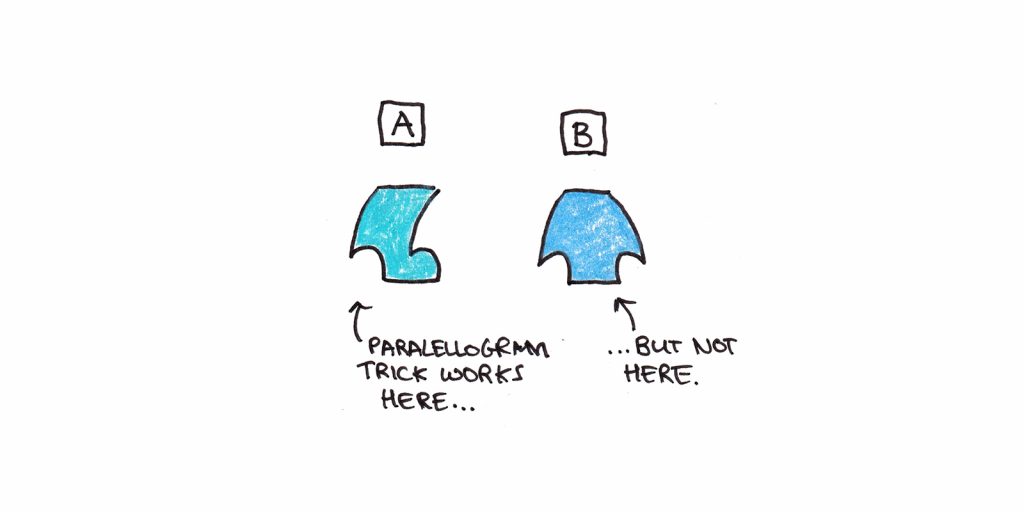

Wertheimer distinguishes between A and B processes. A processes are those where the same principle underlies two problems, even if they are superficially distinct. B processes are problems that look similar, but applying the same principle to both won’t work.

Consider the process for solving the area of a parallelogram: “rearranging” the shape allows us to find the area using a simple formula. This same process can be used to find the area of the A shape because the protrusion on one side matches the indentation on the other. Yet, this process won’t work on the B shape, where the principle is violated.

In many ways, Wertheimer’s book foreshadowed the cognitive revolution, back in a time when behaviorist principles were dominant.

5. Word Problems by Stephen Reed

The psychology of solving algebra word problems might seem an unimportant topic. However, I am interested in it because it seems to be an example of the difficulty observed with transferring what we learn in school to real-life problems.

Word problems are hard, yes, but they’re hard precisely because they ask us to transform real situations to be solvable with methods learned in school. How do we do this?

Reed explores many different factors that contribute to the difficulty of word problems. For elementary arithmetic problems such as, “Bob has eight marbles, and Jim has six. How many do they have altogether?” it seems like a central stumbling point for young children is linguistic. They may not understand what “altogether” means or that it implies addition.

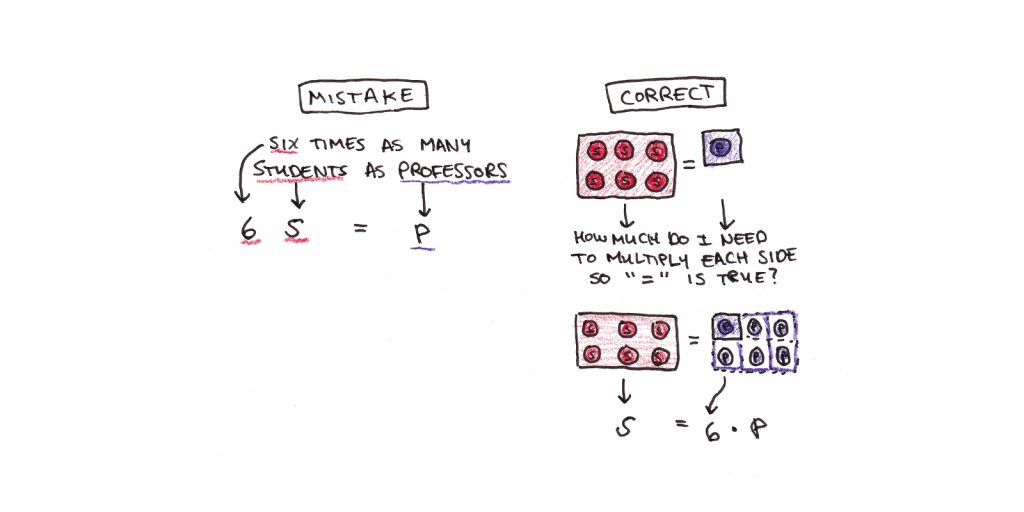

For algebra word problems, the problem seems different. Looking at their errors, students don’t struggle with the algebra but with correctly mapping the situation onto the set of equations implied by the problem. It seems disappointing how bad most people are at this. Most college freshmen, for instance, get wrong “There are six times as many students as professors.” Most people map this as 6S = P, when it should be 6P = S.

Word Problems illustrates both the importance of mastering mathematics knowledge for solving quantitative problems and how we do students a disservice when we don’t equip them with tools for translating this mathematics knowledge to real life.

6. Self-Insight by David Dunning

Dunning is most famous for the Dunning-Kruger effect, which comes from a study showing that most students over-predicted their relative performance on a test. The only exception was the best students, who slightly under-predicted their score.

In Self-Insight, Dunning marshals a large body of evidence showing that we’re terrible at knowing ourselves. We misjudge our competencies, choices and character. My favorite piece of trivia was that people were about as good at judging someone else’s IQ after watching a 90-second video of them talking, as people are at judging their own IQ.

What explains our dismal self-assessment abilities? Dunning prefers a cognitive explanation. He argues that we misjudge ourselves not because we’re lazy or lying, just that self-assessment is a very hard problem. We get inconsistent feedback, struggle to imagine ourselves in different situations, and have little to go on when assessing our aptitude.

I wasn’t entirely convinced. It seems unlikely that we can systematically assess others much better than ourselves for merely cognitive reasons. Instead, I believe social desirability bias plays a much bigger role. Much of our reasoning aims not to solve problems, but to create justifications for our social selves. Thus, many cognitive biases don’t seem like genuine mistakes, but areas where evolution distorts our beliefs to improve our self-presentation.

That said, Dunning does give some interesting counter-evidence to this view. For instance, we seem far more accurate at judging our athletic ability than our intellectual skills. Monetary payments don’t seem to make much difference in our accuracy either.

Regardless of the cause, the difficulty we have in forming accurate self-beliefs seems like a major problem on the road to self-improvement.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.