Pedigree is an eye-opening book. Author and sociologist Lauren Rivera looks into the recruitment practices in elite law, banking, and consulting firms. Rivera’s unsettling portrait provides much ammunition for those who would argue that meritocracy is a myth.

In particular, Rivera finds:

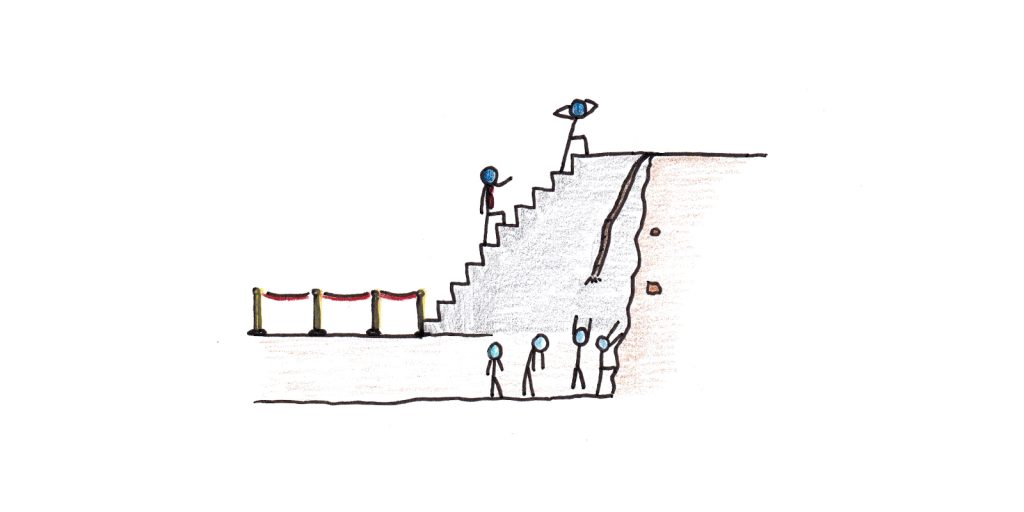

- Alma mater is all-important. Elite firms draw from “core” and “target” schools. Students from core schools are wooed aggressively by firms. You might squeeze in from a target school if you’re near the top of your class. Everyone else might as well not apply.

- Extracurriculars matter more than grades. Firms sought out applicants with interesting and impressive leisure activities. Those who had perfect grades but studied too much were “nerds” and generally excluded. Working on the side to pay for college was also penalized as it failed to demonstrate “intrinsic” motivation.

- Firms prioritized “fit.” Ostensibly, fit refers to the ability of new recruits to integrate smoothly into the corporate culture. In practice, it usually just meant that the applicants were similar, culturally and socially, to the person interviewing them.

- Minorities were held to a higher standard. Men would often get a pass for math mistakes. In contrast, these were seen as proof of low quantitative ability in women. Black applicants were often rejected for lacking polish, but the same behavior in white applicants was seen as fixable with coaching. Stereotyping could cut both ways; for example, dramatic “rags to riches” stories could be a selling point. Yet, if minority candidates’ performance activated a negative stereotype, it could lead to immediate rejection.

- Mastery of subtle class signals was essential. Many qualities required applicants to navigate a delicate and hard-to-fake balance between two extremes. They should neither be arrogant nor meek. They should be active conversationalists while never talking over the interviewer. They should tell personal stories but keep them professional. Those socialized into the American upper class strike that balance intuitively, but it can feel unnatural for non-Americans or those from the working class.

She concludes that hiring depends much more on signaling class status than cognitive skills. Elites put their thumbs on the scale to help their own. Everyone else gets left out. Yet it is rationalized as simply a neutral quest for finding the best.

Understanding How the Game is Played

This portrait mirrored my own experiences attending a decidedly non-elite business school.

I grew up in a small town. My parents were teachers, so we weren’t working class, but most of my friends were.

I chose the same local university my parents attended. I didn’t bother applying to faraway, elite schools. I didn’t know anyone else who did, and I figured the material taught would be essentially the same anyway.

The recruiters Rivera studied would equate this choice with moral failing. Recruiters assumed students always went to the best possible school they could attend because that’s how the game is played. Failure to attend the best possible school was always a sign of either insufficient ability, ambition or both.

Once enrolled, I decided to attend business school. Naively, I thought it would help with starting a business, even though most classes are for middle management jobs.

Again, I made the error Rivera associates with working classes—assuming education is about gaining knowledge rather than signaling your intellectual and class pedigree.

In business school, I witnessed an attenuated version of the class signaling Rivera describes. Many extracurricular activities were seen as more important than classwork, and I overheard more debates about tailoring than academics. Students’ sartorial choices were commented on, and those (usually less affluent) students who wore ill-fitted suits or the wrong tie-shirt combination attracted ridicule.

This isn’t to complain about my school experience as a whole. I had a fun time in college, and later events have certainly been kind to me. Yet Rivera’s description felt uncannily familiar.

How Much Do Skills Matter for Success?

Given that my personal history seems to corroborate Rivera’s account, why do I emphasize learning as a path to career improvement? Rivera’s recruiters didn’t seem to think mastery of academic materials mattered much. Elite credentials and upper-class leisure pursuits seemed to matter more.

Even so, there are a few ways to salvage the role of acquired mastery:

- Recruiters ignored grades because the students had already crossed a high bar to get into the schools they recruited from. Further scholastic achievement has diminishing returns once you’re already at the top of your class. As one recruiter described the work students did in these firms, “it’s not rocket science.”

- Professional services rely more on social skills than technical skills. It would be intriguing to pair Rivera’s account with recruitment at elite engineering firms. I suspect mastery of skills would matter more in engineering simply because the skills required for superior performance are much harder to pick up solely on the job.

- Academic knowledge is overrated. Some skills are best learned in school, but others must be learned through practice. Some of this might be because the latter are highly specific and thus vary from job to job. Some of it might be because the skills are inherently interactional. In these cases, real work experience is required, and academic simulations have limited usefulness.

Elite professional service firms seem to operate according to the same principles as luxury handbags. Clients pay exorbitant fees for first-year law associates, not because they’re brilliant legal theorists, but because they lend prestige via their elite schooling and upper class socialization.

While nice, the material properties of the leather Hermés uses to make its handbags is not why they cost tens of thousands of dollars. Similarly, it isn’t the acquired cognitive abilities of students that make them expensive in elite firms. That said, it would be a mistake to conclude that material properties never matter to apparel companies or that skills are unimportant to all employers.

How Do Skills Matter?

Despite these qualifications, Rivera makes some key points about the ways skills matter:

- Skills and signals are intertwined. Employers can’t see an employee’s productive potential until hiring and training them. Instead they rely on proxies: credentials, interview cases and professional polish. Making improvements in your professional life isn’t merely about acquiring new skills—it’s also about finding effective ways to demonstrate those skills.

- Acing a job interview and being an ace in your job may have surprisingly little overlap. Most recruitment strategies are informal and imprecise. Countless studies attest to the relative worthlessness of interviewing for predicting employee potential. Employers think they can spot talent, but they’re probably kidding themselves.

- Cultural know-how matters more than you think. Figuring out the “rules of the game” is difficult, because they’re rarely stated and the best players think they’re obvious. But understanding these rules early can have enormous dividends. Rivera notes one Indian applicant who was stellar, but didn’t realize how important extracurriculars were in American recruiting. Joining intramural groups late in college didn’t count as the intensive commitment that signaled intrinsic motivation to recruiters. She didn’t get the job.

All of this, to me, suggests that skills need to be viewed in a proper context. You should have some good reason to think a skill matters before pursuing it to help your career. Knowing the rules of the game you’re playing can help you decide whether a skill investment is likely to pay off.

The Irrelevancy of Unfairness

The intended reaction to Rivera’s book is one of concern, pessimism and maybe even disgust. It’s hard to read without feeling that the game is rigged, and perhaps we’d all be better off if people had nothing to do with it. It certainly didn’t inspire me to seek a banking job.

But that feeling is somewhat beside the point. Every field has its own structures of success and gatekeepers who throttle access. There will always be some skills that matter and some that don’t. Hidden rules of play are treated as obvious by those who succeed but poorly understood by those outside. Wherever you are, if you want to play, study the game.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.