If I made you take the final exam for a class you studied a decade ago, would you pass?

The unfortunate truth is that, except for knowledge we actively use in daily life, much of what we learn is beyond our powers of recall. But that doesn’t mean it has been erased from our memories.

Why We Forget

Early theories of forgetting were based on decay. These theories assume unused memories fade with time like the yellowing of a photograph. The idea has some intuitive plausibility. Physical atrophy withers the body, so why not the delicate connections that store our thoughts?

Yet, the theory of decay is not the whole story. As psychologist Robert Bjork comments:

“Thorndike’s original law of disuse, of course, stands as one of the most thoroughly discredited of the various ‘laws’ psychologists have put forward over the years—which is a considerable distinction.”

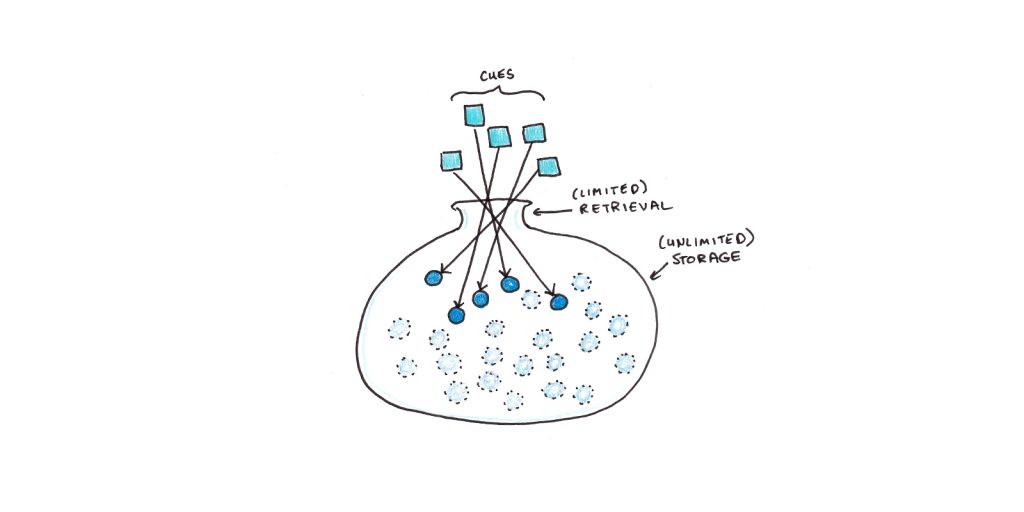

Interference from other memories is another major factor in forgetting. Retrieving a memory is an active process. You need to search for a specific memory based on cues you have consciously accessible. As you acquire more memories, more and more of them become associated with familiar cues. It becomes harder and harder to retrieve any particular memory.

This may seem like a defect, but it’s actually a feature. Memory is only useful if we retrieve the right memories at the right times. Recalling the right memory requires both retrieving the correct option and suppressing all competing alternatives. Otherwise, our waking life would be a dreamlike flood of irrelevant and dissociated thoughts—hardly a sound basis to make intelligent decisions.

Forgetting Can Be Good for Learning

The adaptability of memory goes further. If a memory turns out to be surprisingly useful—i.e., we retrieve it despite barely remembering it and find it to be the answer we want—the memory becomes much easier to recall than if it was easy to retrieve.

This is the basis behind Robert Bjork’s concept of desirable difficulties. We benefit more from remembering something when the cues that bring up that memory are weaker. Thus testing beats re-reading for studying, spaced practice beats cramming and mixing up problem sequences is better than doing them in batches.

This desirable difficulty isn’t a design flaw. It underpins a highly sophisticated selective recall strategy. If information is only relevant given highly predictable stimuli, that itself is a signal not to retrieve the stored memory in other contexts. Useful retrieval in contexts where the cue is not obvious suggests the memory needs to be more broadly accessible.

Another implication of this theory is that storage and retrieval become dissociated. A memory could be highly learned, and thus well-remembered, but unretrievable. You could detect this by giving another learning trial, in which case the memory becomes learned much faster a second time.

The Power of Relearning

After years of absence from studying a topic, it’s common to feel you’ve forgotten everything. Forgetting can be embarrassing or frustrating as you realize that you can no longer do things you had previously mastered. Yet is this correct?

Research on memory suggests otherwise. Relearning tends to be much faster than initial learning. And thus, even in extreme cases where the entire class seems unfamiliar, you still acquire the skills faster in a second passage.

I’ve experienced this with many of the skills I’ve learned. It can be painful to attempt a conversation in a language I haven’t practiced for months. I had a similar frustration trying to grasp calculus when I decided to study quantum mechanics after several years of mathematical quiescence. In these cases, there can be a pang of doubt: did I even really learn this in the first place?

Even so, relearning is something to celebrate, not to be embarrassed by. The mistake isn’t having forgotten, but in letting a temporary drop in ability keep you from learning again.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.