In the previous essay in this series, I complained about how we were never taught how learning works. As a result, we often guess at which methods to use when studying. Sometimes, we guess badly.

To illustrate, here’s a question for you: when studying for a test, which matters more, the method you use, or how motivated you are to learn the material?

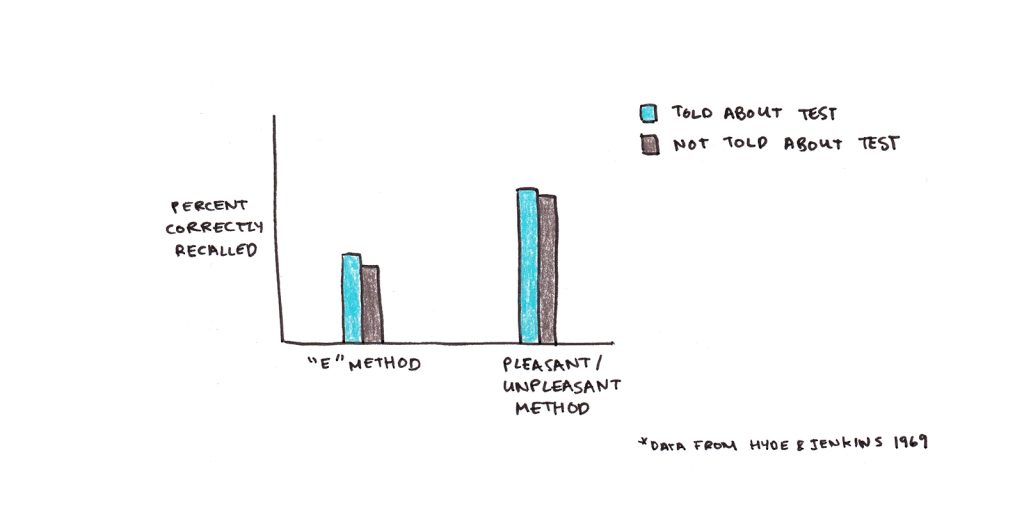

That question is a bit vague, so let’s make it more concrete. Suppose I read out loud to you a list of words. Now imagine I gave you one of two techniques to use: hearing each word and asking whether it contained the letter “e” or asking whether the word felt pleasant or not.

Now suppose I tested you under two conditions: in one condition I told you that immediately after I read the words, I’d test how many you remembered. In the other condition, I didn’t tell you about the test at all, I merely asked you to go through the two different procedures while hearing the words.

Given the two conditions: different methods for learning or different amounts of motivation to study, which do you think made a bigger difference on test performance?

The answer may be surprising: only the method mattered, motivation didn’t matter much at all.

Why We Deceive Ourselves About What Works When Learning

Perhaps, you might be thinking, this test isn’t a fair one. After all, having lots of motivation often leads to using better studying methods. It also determines how much time you spend studying. After all, if you aren’t motivated, you probably won’t buckle down and learn the material.

This is true. But if the above experiment surprised you, perhaps you should question how “obvious” many other pieces of studying lore are.

In fact, students frequently misjudge the efficacy of their studying. In an experiment by Jeffrey Karpicke and Janell Blunt, they asked students to read a passage and study with one of four different techniques: concept mapping, repeated reading, single reading and free recall. Before being tested, they asked how well they thought they’d do on the test.

The students couldn’t have been more wrong. The ones that used free recall thought they’d perform worst, but actually performed best! Repeated reading (a common studying approach) doesn’t work very well, but it leads to high confidence.

How do we trick ourselves into using methods that don’t work? Psychologist Robert Bjork explains this as a quirk of how our minds work. When we try to assess how well we’ve learned something, we can’t actually see the neural rewiring taking place. Instead, we can only gauge how easy it is to think about the material. This ease is often correlated with learning—think about knowledge of your favorite television show versus knowledge of quantum physics. So the heuristic of substituting ease for learning isn’t always a bad one.

Yet this heuristic works poorly when comparing studying techniques because the methods that feel harder often work better, as indicated in Karpicke and Blunt’s study.

Going Beyond Guessing

We need to go beyond guessing in figuring out what works for learning. This is partly because our intuitions are often deceptive: we substitute ease of processing for depth of learning, and we make motivation all-important—without recognizing that tons of motivation can’t fix a lousy method.

Instead, you need a system. You need to understand how learning works, and how you can make best use of your time to make a difference. If you’re going to spend years of your life learning, you owe it to yourself to invest in a system to learn better.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.