Reader Talal asks:

I have a question:

- Single variable calculus (MIT)

- Mathematics for computer science (MIT)

- Harvard CS 50 (Harvard)

- Intro to algorithms (MIT)

- Design and analysis of algorithms (MIT)

- Leetcode practice problems

Are taking these courses enough if I want to get a job at big tech company?

Not being a professional programmer, I’m going to dodge the specifics of Talal’s question. (Although, anyone who does have experience here is welcome to weigh in!)

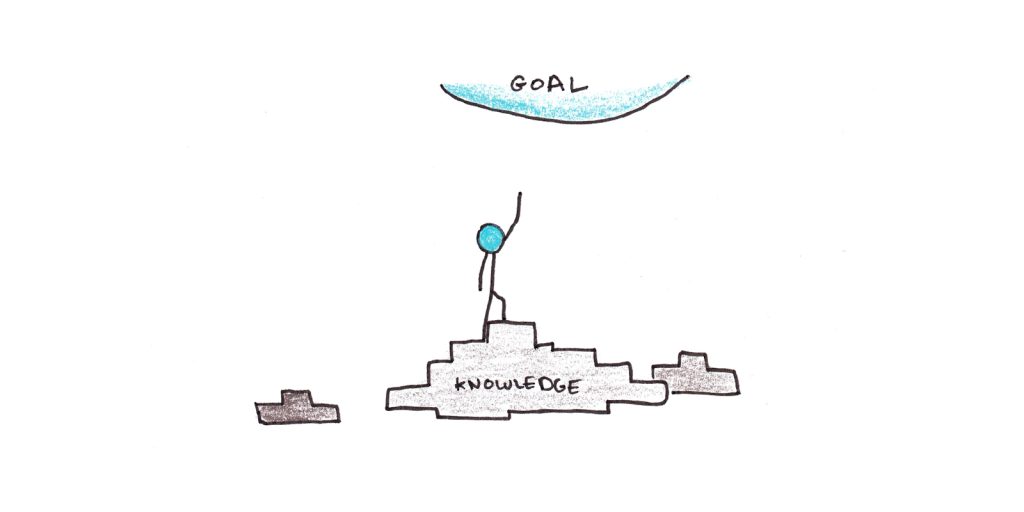

Instead, I’d like to use this question as a jumping-off point to discuss a broader question. How do you reverse engineer the learning required to achieve a particular outcome (getting a job, passing a test, proficiency in a skill)?

Learning Basics and Learning Backwards

In general, I think there are two mindsets you can apply to learning:

- Start with the basics. In this case, you identify the foundational skills and concepts and work toward broader mastery from the basics.

- Master a criterion task. Here, you start with the end goal, figure out what you are missing and strive to learn it.

Both approaches have merit, but they have different strengths and weaknesses.

Given Talal’s course choices, it seems he may not have a lot of programming experience (or he has programming experience but little formal computer science training). In this case, there’s probably a lot to learn, and proficiency won’t happen overnight.

In this kind of case, I think the strategy of starting with some foundational courses is reasonable, even if those courses alone won’t be sufficient for landing a job. Having some basic idea about how algorithms work, how computers work and how programming generally works is a good idea.

In contrast, if Talal already has a computer science background, taking more and more foundational classes would be unlikely to meet the goal he has in mind. Instead, he would need to work backward. He would need to figure out what specific skills are sought in programming interviews and ensure he has the required competency. If the skills of interviewing and performing on the job are different, he may need to master those too.

Working backward is important because most skills are fairly specific. There isn’t much payoff for practicing skills that differ considerably from the tasks you’re trying to master. Spending your time learning about general programming concepts will be much less efficient than practicing the skills needed to write good code and answer technical interview questions.

When Should You Start with the Basics?

Starting with the basics, and ignoring the specific test criteria, is best when cognitive load is high.

Cognitive load refers to how much you need to juggle mentally to understand a new idea. It’s why quantum mechanics classes are hard and why you can’t easily repeat back a sentence spoken to you in an unfamiliar language.

Cognitive load isn’t fixed for a subject—it depends on your prior experience. Familiar patterns don’t use up as much mental bandwidth as unfamiliar ones. This is why learning the tenth word in a new language is much more effortful than learning the 1010th. By the time you get to the latter, the basic patterns of pronunciation and orthography are so familiar that the word “clicks.”

Some subjects intrinsically have a higher cognitive load than others.

Programming, for those without a background in it, is famously high in cognitive load. Everything looks alien and arbitrary. It takes a lot of work to understand what a variable is, what functions are, how pointers work, or why anyone would bother using recursion. You must grasp many individual elements to appreciate a programming design pattern.

In contrast, smaller elements of programming, such as the specific spelling of individual functions, may be low-load—you can pick them up just through regular use.

The higher the cognitive load you’re experiencing, the more it helps to start with basics. Getting an introductory programming book, learning the theory and ideas, and getting lots of practice can make it feel easier.

When Should You Start with the Outcome?

Starting with the specific test requirements makes more sense once you have mastered the basics. There are two reasons for this:

1. The knowledge needed to perform explodes beyond the basics.

You can have a (simple) conversation with less than a thousand words in a language. But full fluency likely requires fifty times this vocabulary. As you get deeper and deeper into infrequently used words, tailoring which words you learn to the situations you’re likely to encounter begins to pay off.

This is the basic pattern for all skills. The more advanced you get, the more numerous and specialized your knowledge becomes. As it can take a lifetime to master even a subspecialty, it makes sense to work backward from the end goal.

2. Application of knowledge starts to dominate acquisition of knowledge.

Abstractly knowing the right answer is rarely enough. You need to be able to retrieve it and apply it to the specific question you face. This, in turn, requires a lot of practice.

Most people who have studied CS would be able to say what a pointer is. But they might struggle to debug a program that has an error in how a pointer is dereferenced. To be useful, you need to be able to retrieve knowledge in the appropriate contexts. That requires practice in situations similar to those you’re likely to encounter.

Fluency in complex skills depends on rapid, automatic access to knowledge. It’s one reason we often make a distinction between knowing about something and being able to perform proficiently in it.

Merging the Strategies

I generally try to do a bit of both when approaching a new learning project.

I often start by looking at the criterion task. If my knowledge is relatively weak, I’ll use that task to assess which broad topics or subjects I need to study. If I am expected to show competence in algorithms, I’ll take a few classes in algorithms.

As I get further along, I spend more and more time focusing on what is needed in the specific situation I’m going to face. Practice questions that are highly similar to those on the test are the best starting point. If those aren’t available, practice that is at least as difficult and covers the kinds of situations you face is probably helpful.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.