Peter Drucker, the eminent management theorist who coined the term “knowledge worker,” made a compelling case for figuring out where your time goes:

Effective executives, in my observation, do not start with their tasks. They start with their time. And they do not start out with planning. They start by finding out where their time actually goes.

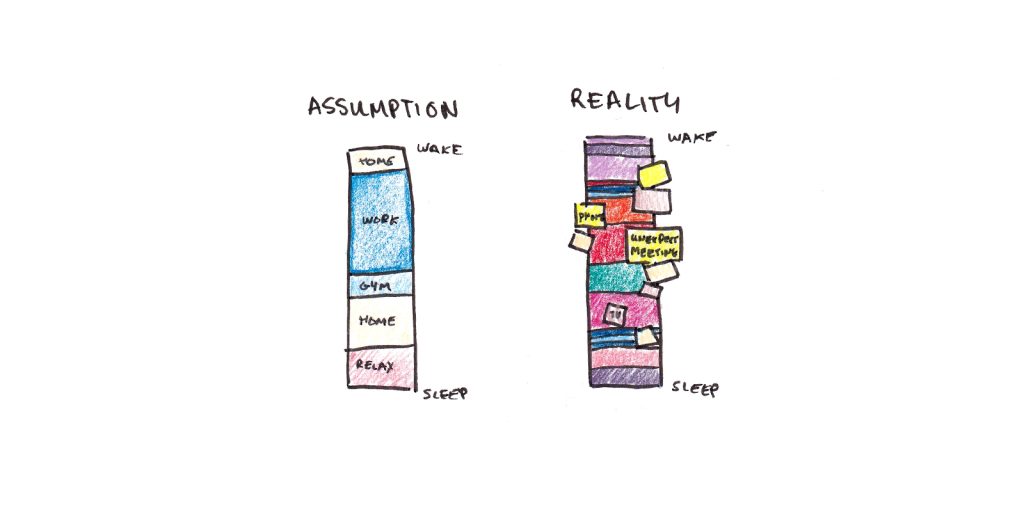

One difficulty of gaining focus is that we rarely know where our attention goes. How much time do we spend on email versus doing our most valuable work? How much time do we spend scrolling social media versus seeing our friends in real life? We feel overwhelmed studying for a big exam, but how many hours went to actual studying, and how many were spent just worrying about it?

For most of us, we don’t know. Without knowing where our time goes, how can we possibly improve it?

Over fifty years ago, Drucker identified the first step: take a detailed log of all your activities, with the start and stop time for each. This will let you know where your time is going.

Complete vs. Cursory Time Logs

The ideal time log would track all activities across your entire day. That way you would have a detailed accounting of how much time you spend watching television, using your phone, playing with your kids, doing household chores and, of course, actually working.

I’ll call this a “complete” time log since it is quite granular in tracking how your attention gets spent. Unfortunately, complete time logs are also tedious to do. There are phone and computer apps that can help automate this tracking, but they often still need some manual intervention. (For instance, is my checking a website research for an article or slacking off?)

However painstaking, everyone would benefit from doing a complete time log for a day or two in their lives occasionally. Even if you’re busy to the point of exhaustion, it’s often surprising how much of your time gets wasted.

Long-term, however, a better tool is to keep what I call a cursory time log. You use this time log to track one or two categories of time spent. In Life of Focus, we encourage students to engage in this kind of time logging by keeping a deep work tally, marking the start and end time of every deep work session they do.

A cursory time log, lacking details, can make analysis harder. You won’t always know the exact reason for changes in your working patterns. But, in some ways, the lack of details is an asset. A deep work tally, for instance, helps you detect at a glance whether the amount of time you are investing in important work is changing.

You can only change something if you’re aware of it. If you want to spend more time on the things that matter to you, the first step is figuring out where your time is actually going.

Next week, Cal Newport and I are starting a new session of our course, Life of Focus. Over the next three months, we’ll work with a group of students dedicated to improving their ability to focus on what matters.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.