Our deepest beliefs are often girded by assumptions we rarely articulate. The mindset of efficiency is one of mine.

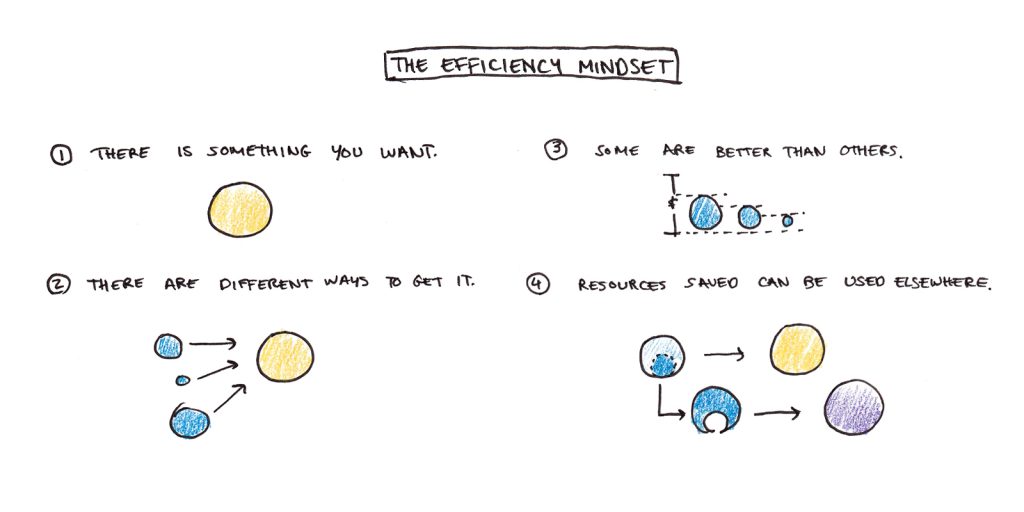

The assumptions of this mindset are essentially:

- There are things we want.

- We can take actions to get the things we want.

- Some actions are more efficient than others—i.e., they will get more of what we seek for less time, effort, money, etc.

- The resources we save by being more efficient can be spent on other things we want.

To consider a concrete example, think of a task like studying for an exam:

- There is something you want: to pass the exam and learn the material.

- There are actions you can take to get what you want: studying.

- Some actions are more efficient than others: some methods of studying result in more learning than others.

- If you use more efficient methods to save time studying for the exam, you can put that time toward other activities you enjoy.

The efficiency mindset applies broadly because these assumptions apply to many things. But it’s also important to note where they break down.

Where Does the Efficiency Mindset Break Down?

A common criticism of the efficiency mindset is rooted in an overly-narrow interpretation of assumption #1, the things you want.

Consider speed reading a novel. This is “efficient” in the sense that you’re getting through the book in less time. But is that really what you want?

Much of the value in reading a novel comes from enjoying the plot, dwelling in the world of the characters, or pondering the book’s deeper meanings.

When efficiency often fails, it is usually because we’ve adopted an overly restrictive, incomplete, or inaccurate view of what’s valuable about the activity.

While this is a wrinkle in applying the efficiency mindset, it’s not a compelling argument against it. If you incorporate all the things you value, appropriately weighted, then the efficiency mindset still works. It’s essential to include things like “enjoyment” and other often-overlooked values when considering the efficiency of reading novels.

The real failure of efficiency isn’t an overly narrow conception of what we desire, but when assumption #4, that you can reinvest resources saved by being more efficient, breaks down.

When Working Harder Only Creates More Work

Central to the efficiency mindset is the idea that the time or resources saved through efficiency are fungible. You need to be able to take the time, money or effort saved on doing one thing and apply that to something else. If you can’t reinvest the resources, doing things more efficiently doesn’t pay off.

As a teenager, I worked at a video rental store one summer. Being more efficient working at the store was kind of pointless. The boss would exhort employees to spend idle time cleaning the shelves or tidying the display racks, but people seldom did. When the store wasn’t busy, we just lounged around. When there were tasks to be done, nobody was in a hurry to finish them quickly.

The fact that nobody (except maybe the manager) thought about efficiency made total sense. Working harder didn’t pay off. Our hours were set, we earned minimum wage, and there weren’t performance bonuses for extra effort. Nobody was angling for a promotion or hoping to move up the video-rental corporate ladder. If you finished your work early, there was only more busy work. You didn’t get to do anything more interesting with the time saved.

Additionally, in that environment, working more efficiently was socially costly. Hanging out with the other staff was the only glimmer of joy in an otherwise mindless job, so if you became the person who got everything done with speed, you made your other coworkers look bad.

I’m sure management’s perspective was that we were all just lazy. We were paid to be there and work, so why didn’t we work as hard as possible? But from our perspective, as long as we met our actual job requirements, there was no reason to be any more efficient.

I sometimes think about those days because my current life is worlds apart. I’m my own boss, and my income, free time and personal success depend entirely on my efficiency. However, I’m also aware that if you’re used to environments with no reason to be efficient, “efficiency” is just a byword for what the boss wants you to do.

Efficiency is a Novel Concept

I mention that experience because across different cultures and social organizations throughout human time, I think the situations where it paid to be efficient were relatively rare.

I can’t find the source now, but I recall reading a book where Western researchers came to investigate a remote tribe that engaged in some subsistence agriculture. The tribespeople surveyed often complained about being hungry, wanting more food. But, to the investigator’s eyes, they seemed, well … kinda lazy. They didn’t do what seemed obvious to the anthropologists, simply growing more crops so they’d have more to eat.

The authors claimed this had to do with the social organization they lived in. Supposing you did grow a surplus of food, you could eat as much as you want. But in the close-knit band you lived in, sharing was required. So distant relatives who were hungry would complain to you to give them some of your food. The industrious subsistence farmer wouldn’t have much incentive to work hard since any surplus would likely be taken away.

As this is beginning to sound like a cloaked libertarian allegory, I think it’s worth pointing out that even in societies with strong social welfare states and progressive redistribution policies, we still get to keep most of the fruits of our labor.

Instead, the point I’m trying to make is that the benefits of efficiency are a rather unusual feature of modern societies and that, at most points in time, we were probably like the “lazy” subsistence farmers who couldn’t see the point of being more efficient. If efficiency seems unnatural to us, it might be because, throughout our evolutionary history, working really hard to generate surplus wasn’t often a sound strategy.

Are You Lazy, Or Is It Your Workplace?

Most environments we work in exist on a spectrum. At one end are the dead-end video rental jobs or tribal subsistence farmers where the idea of efficiency is alien and unrewarding. At another extreme are the scenarios where efficiency is obsessed over because any gains are personal rewards.

Work cultures exist on a spectrum too. I previously discussed an interesting description of Japanese office culture, which appears to prize working extreme hours at the office (with the result that employees are often terribly inefficient). On the other extreme are results-only work environments, where pay is exclusively based on performance (but that performance can be difficult to track and assess fairly).

I suspect that when productivity feels like a chore rather than an opportunity, it’s less because we’re intrinsically lazy and more because our environment makes us that way.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.