Last week, I started discussing the fifteen thinkers who have most influenced my perspectives on learning, starting with the cognitive scientists who have given me my basic mental models for how learning actually works.

Today, I’d like to focus on a more eclectic mix of thinkers who have informed my understanding outside the narrow confines of cognitive science.

To read the first part, covering influences one through seven, click here.

8. Jean Lave

A major tension in my thinking is the relationship between academic skills and real-world competency.

On the one hand, I value learning and education and spend a lot of time trying to learn academic skills and subjects. I believe skills underlie a lot of professional success; thus, our ability to learn well directly contributes to our material well-being.

On the other hand, there are valid critiques of schooling. Bryan Caplan has made the case that much of the value of formal education is signaling—that academic skills and knowledge are unimportant for doing good work. Other writers have argued from survey evidence that many employers seem not to care so much about academic skills in hiring, preferring work experience instead.

In this debate, I’ve found Jean Lave’s anthropological work fascinating. Beginning with a study of West African tailors, she observed that most became competent in their craft with little direct instruction. This encouraged her to adopt the view that learning is social, not cognitive. By this paradigm, learning doesn’t take place primarily in our heads; instead, it’s a cultural activity we participate in.

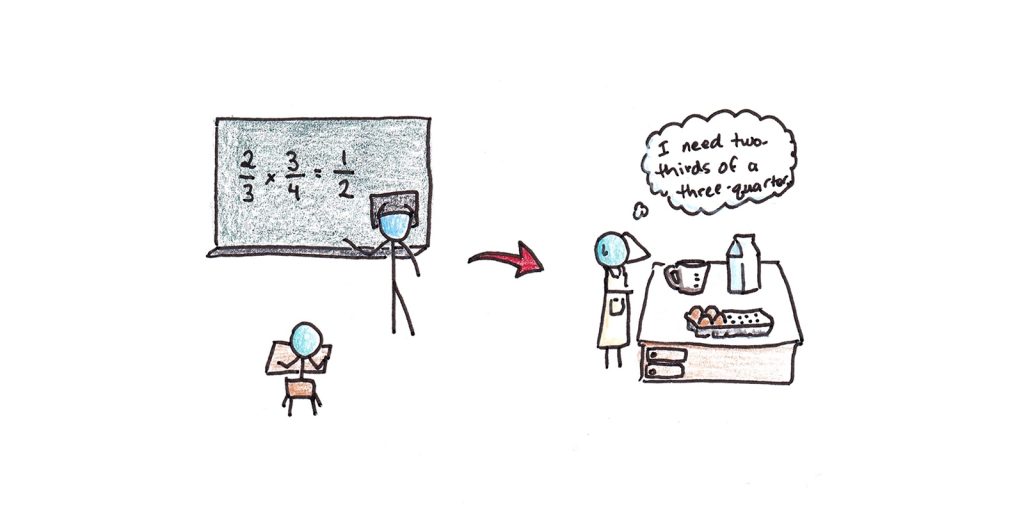

Another provocative book by Lave follows everyday people as they use math in their lives. She found that they rarely followed classroom algorithms but performed competently nonetheless. One of her most interesting findings was that many people struggled to get the right answer to math problems when they were framed as classroom problems—despite correctly solving the same problems “in the field.”

I don’t agree with all of Lave’s thinking. For one, she steadfastly rejects cognitive explanations of learning, which are central to my perspective. Second, she seems to reject the didactic style of instruction, which I believe is more effective.

However, I find Lave’s work intriguing because it covers a topic that is rarely discussed elsewhere—how learned skills apply to real life. There are many experiments on how skill development works, but far fewer careful studies show what kinds of knowledge and skills people use in practice. This results in a plethora of ideas on how to enhance learning, and a paucity of ideas on which skills are most worth learning.

If you’re interested in reading more, I recommend:

- Situated Learning — This slim volume covers her philosophy of pedagogy, inspired by apprenticeship.

- Cognition in Practice — Her “real-world math” book covers the fascinating (and controversial) research on how people use math in everyday life.

9. Albert Bandura

Albert Bandura has influenced my thinking in two crucial ways.

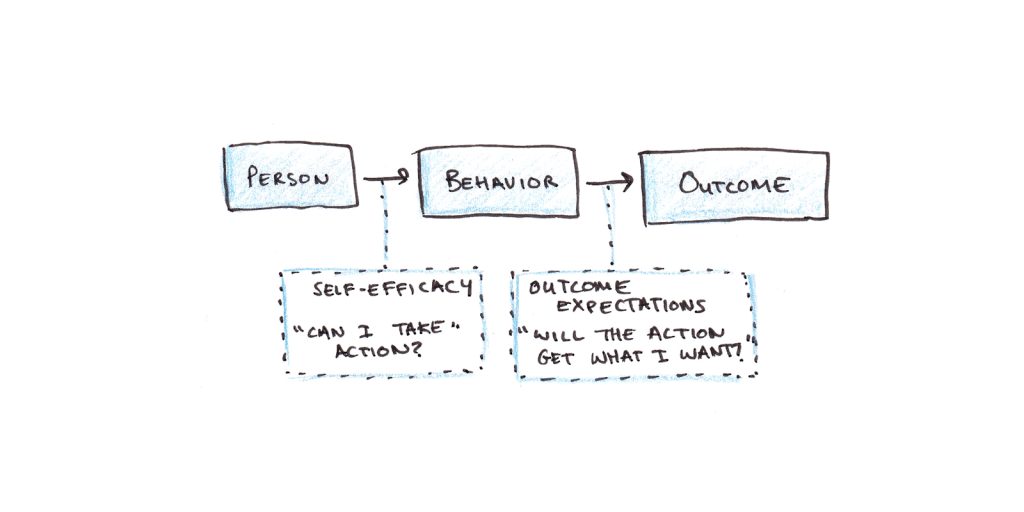

The first is his concept of self-efficacy, which I’ve explained in detail here. His idea was that motivation isn’t simply the rational calculation of expected benefits, but is influenced by our beliefs that we can (or can’t) execute the required actions. Many people know they need to overcome their fears, apply for a new job, seek out friends or start exercising, but fail to do so if they maintain low self-efficacy for the actions they need to take.

The second is his social learning theory, the idea that most of what we know how to do comes from observing other people, not trial-and-error on our own. Behaviorists centered their explanations of human actions around reinforcement and punishment, which overlooks that humans are a social, cultural species. We may use reinforcement to guide our choices, but we mostly figure out how to do anything by watching other people.

In some ways, any description of Bandura’s ideas does a disservice to the quality of his thinking. That self-confidence matters for motivation, or that it’s easier to learn when you’re shown how to do something, are hardly radical ideas. But his writing also lucidly and intelligently defuses other plausible, competing theories that would reject these commonsense premises.

If you’re interested in reading more, I recommend:

- Social Learning Theory — Bandura’s excellent book.

- Self-Efficacy — His paper on the concept has been cited 100,000+ times.

10. Barbara Oakley

The first person on this list I can call a personal friend, Barbara Oakley has been an inspiration and influence to me ever since the first session of her wildly popular course, Learning How to Learn.

Oakley has written several excellent books on learning and teaching. Her writing builds upon the work of Sweller and others, but she also draws on a lot of neuroscientific research in informing her advice on the right way to learn and study.

More than anything, Oakley is one of the nicest and most helpful people I’ve met in all my years of writing. She is encouraging to a fault and a big believer in the power of people to change how they learn. She did it herself, earning a PhD in engineering, despite being someone who didn’t initially feel she was good at math.

If you’re interested in reading more, I recommend:

- Learning How to Learn — Her mega-popular Coursera course, taught alongside eminent neuroscientist Terrence Sejnowski.

- A Mind for Numbers — An excellent book on the research behind learning math and technical subjects.

11. Benny Lewis

As I document in my book, Ultralearning, Benny Lewis was the biggest influence on my embarking on aggressive, public, self-directed learning projects.

I met him during a moment of difficulty. I was living in France, and my French was coming along poorly. His “fluent in three months” challenges were an inspiration, and also a source of envy. His approach on deep communicative immersion, overcoming fear and social resistance to speaking a new language, assisted my French. It also became the bedrock for Vat and my later approach in learning languages during our yearlong adventure.

Some people have criticized Benny for the claim imputed by his website, that a person can become fluent in only three months. Fluency is a vague term, and it’s possible to define it in ways where this claim is achievable (e.g., when the aim is fluid speaking/listening for easy conversations) or unachievable (e.g., when the aim is native-like proficiency in all situations). But I think these criticisms miss the point—to me, the title was never a promise but an aspiration, something to strive to reach, even if we don’t always get there.

If you’re interested in learning more, I can’t recommend anything more highly than Benny’s website.

12. Cal Newport

Cal Newport has been a close friend and mentor for almost as long as I’ve been writing this blog. We’ve also been frequent collaborators on course projects, such as Top Performer and Life of Focus.

Cal started with student-oriented advice books, the best of which is How to Become a Straight-A Student. Cal Newport, himself an accomplished student from elite schools, wanted to dig deep into how some students were able to ace their exams without grinding study routines.

Cal’s answer combines good studying advice with a large dose of good organization and productivity skills. I suspect many students with previously haphazard studying habits (and poor grades) can point to Cal’s book as the inspiration for their transformation into diligent and successful students.

Knowing how to study effectively, and having a system to do so consistently, is more important than raw intelligence for most skills and subjects. While inborn smarts will always give some a leg up, getting organized and studying properly has to be the first step if you’re struggling with school.

For learning, I highly recommend Cal’s student-oriented trilogy:

13. Daniel Willingham

Daniel Willingham is one of my go-to sources for evaluating the evidence on studying and learning strategies. He was one of the authors of an impressive monograph that reviewed the evidence behind ten popular learning strategies. His blog delves into educational research and breaks it down for a lay audience. Finally, he’s written some excellent books on learning and education.

A key theme of Willingham’s work is the importance of knowledge to learning. A common, and misguided, critique of schooling is that it only teaches facts—we need to teach students how to think! Except knowledge is what we think with, and smarter thinking requires having more knowledge and experience.

Another maxim from Willingham that has guided my thinking is “memory is the residue of thought.” What we remember and learn is a function of what we were thinking about and paying attention to during learning.

Many educational practices result in worse learning outcomes because they don’t focus students’ attention on the knowledge and processes needed to build skills. For example, students in science classes may spend hours decorating posters about a topic rather than drilling into the concepts underlying that topic.

If you’re interested in reading more, I recommend:

- Why Don’t Students Like School? — Seven principles of good learning, drawn from research.

- When Can You Trust the Experts? — Questioning the often poor state of educational research, trying to delineate what sorts of science are trustworthy and which aren’t.

- Improving Students’ Learning — A paper he collaborated on, reviewing ten different learning techniques and the evidence for and against them.

- His online essays.

14. Siegfried Engelmann

Direct Instruction is a system of teaching developed by Engelmann and his colleagues in the 1960s. In Project Follow Through, the largest-scale educational experiment ever conducted, Direct Instruction was the most successful program for helping students learn. Since then, countless studies have found Direct Instruction to be successful, particularly with weaker students.

Much of our educational system blames failures to learn on students. They aren’t smart, diligent or attentive enough. Direct Instruction flips this mindset and argues that a failure to learn must always begin with examining the quality of the instruction given. Only if the instruction itself is complete and flawless should we begin to impugn students’ abilities or motivation to learn.

The idea behind Direct Instruction is that skills need to be broken down into their atomic parts, with each part drilled systematically before being built into complex performances. So, learning to read begins systematically with learning to recognize individual letters, learning their sounds, blending their sounds together to create words, and then finally putting them into sentences.

Direct Instruction is often used as a by-word for traditional schooling, and all the negative stereotypes it evokes. However, as I read through Engelmann’s Theory of Instruction, the thing that struck me most was that I don’t recall ever having taking a class taught this way in my entire life!

If you want to read more, I highly recommend Engelmann’s excellent book, Theory of Instruction.

15. Richard Feynman

I’ve read a ton of biographies. While I usually find them interesting, I rarely find myself drawn to emulate the person I’m reading. Famous figures appear heroic from a distance, but they often prove tragic figures when their lives are dissected in detail.

Richard Feynman is different. His attitude and approach to science and learning continue to be a source of inspiration for me today. His unending curiosity, irreverence to authority, and constant hunger to seek a deeper understanding of things have been a guiding star for me most of my adult life.

He is also, perhaps, the source of one of my biggest mistakes as a writer. Shortly after reading his autobiography for the first time, I decided to call a self-explanation technique I had been using “The Feynman Technique.” My memory of the book was hazy, and I remembered him doing something similar in a section of the book.

Something about the usefulness of self-explanations and the association with the illustrious physicist caught on. Countless other explanations of the technique emerged, repeating and strengthening the assertion that Feynman had done precisely this to learn physics.

While I had thought it fairly harmless to name the technique after my intellectual hero, I now see this was a big mistake. My sloppiness as a young writer fabricated a bit of historical trivia that now lives perpetually on the internet. Indeed, it was so successful that my role in naming and associating the technique with Feynman has been completely obscured.

Despite Richard Feynman probably never using the exact technique I named after him, he has always inspired me by his quest to seek a deeper understanding of ideas. In popular media, cleverness is often portrayed as inscrutability.

Feynman showed that true cleverness is simplicity—understanding is the process of making a confusing idea seem painfully obvious, not wrapping it in extra sophistication.

Final Reflections

Part of living a life devoted to learning is expecting that new ideas may change your mind. After all, if you already know everything, what’s the point in learning new things?

I fully expect the list of who most influences my thinking will be different ten years from now. Not only will new research be published that will overturn some old findings or cast prior concepts in a new light, but I’ll finally make my way to reading thinkers and scholars I’ve missed thus far.

All I can promise is that as I learn more, I’ll continue to share my thinking with you!

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.