Psychoanalysis, pioneered by Sigmund Freud, dominates popular impressions of therapy. Patients lying down on long couches while an analyst dissects their dreams for evidence of repressed childhood trauma make for great television, but does it actually work?

In the late 1950s, Aaron Beck, a practicing psychoanalyst, decided to test a key concept of Freudian theory. Psychoanalysts explained depression as a masochistic drive—hostility turned inward toward the self. If that were so, Beck would expect those themes to show up in patients’ dreams.

However, when he scrutinized these dreams, he didn’t find masochistic imagery. In fact, his patients had fewer hostile images. Instead, he found themes of loss and rejection.

This failure of Freudian theory triggered Beck to question his entire discipline’s assumptions. If the theory’s basic tenets couldn’t be demonstrated in experiments, how useful was psychoanalysis?

Cognitive therapy was born out of this failure. In the decades since Beck’s pioneering work, this mode of therapy has proven one of the most effective practices for treating depression, anxiety and many other psychological afflictions. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) often outperforms pharmaceutical drugs alone, and it has become the gold standard for psychotherapy.

What is Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy?

The basic premise of CBT is that distorted thinking causes psychological distress and dysfunctional behaviors.

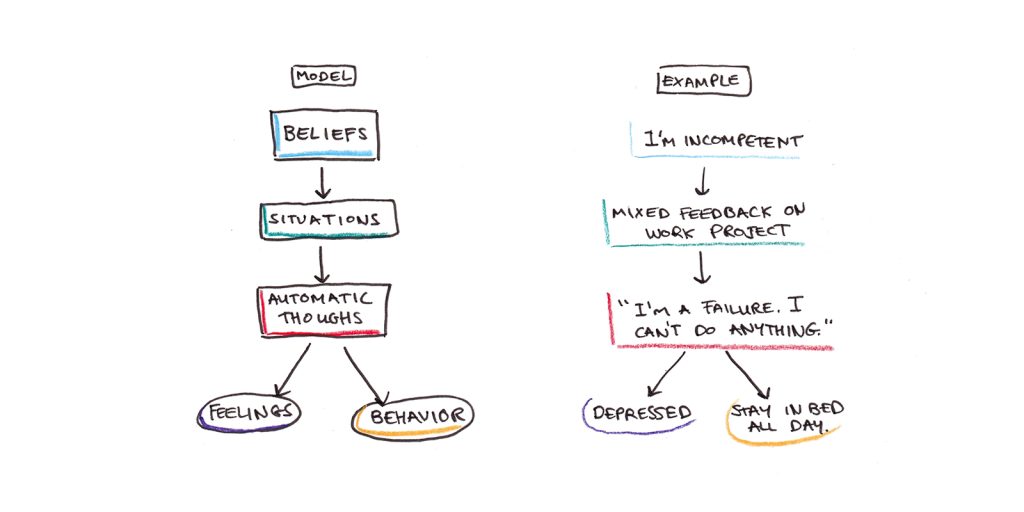

In this model, our beliefs cause us to interpret ambiguous situations in particular ways. These interpretations give rise to automatic thoughts, verbalizations and images that rise to the level of consciousness. Those thoughts, in turn, produce emotional reactions and behaviors.

For example, imagine a depressed person who has a belief that she is incompetent. When she receives a negative performance review at work, it triggers the automatic thought, “I’m such a failure. I can’t do anything right.” The thought then causes her to feel more depressed, further sapping her motivation to work.

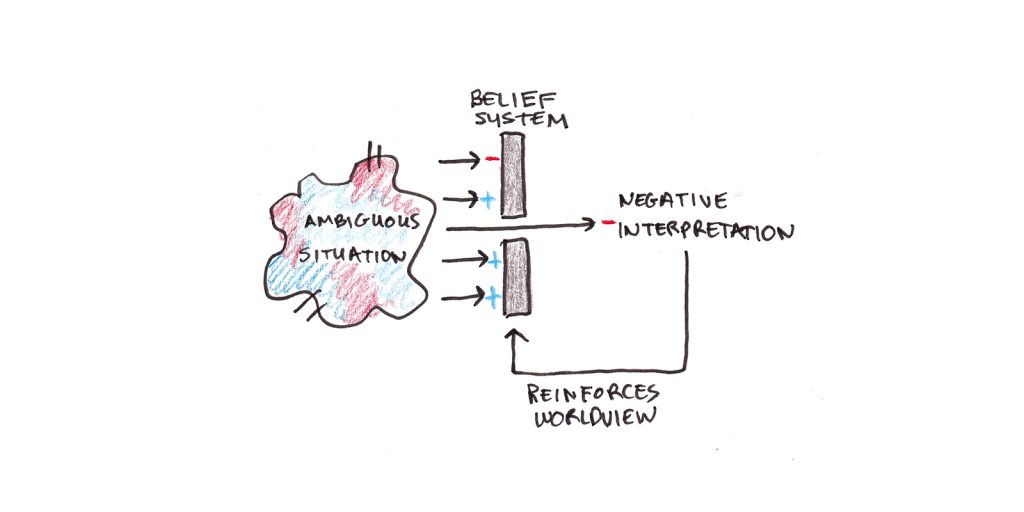

Beliefs, thoughts, emotions and actions can all be mutually reinforcing.

Even if the feedback is a mix of good and bad, the depressive person interprets it in a negative light, triggering automatic thoughts of failure that further depress her mood and make it harder for her to work. This further entrenches the original belief, making similar interpretations more likely in the future.

CBT encourages people to notice and question their automatic thoughts. Then, they use reasoning and experimentation to test their beliefs and adopt more realistic ones. This process leads to healthier thinking, feeling and behavior.

Recognizing Disordered Thinking

Automatic thoughts arise spontaneously, and we have no control over their content. The aim of CBT is not to deny these thoughts; it is to notice them and subject them to scrutiny.

In a leading practitioner’s guide to CBT, Judith Beck (Aaron Beck’s daughter and disciple) lists a number of disordered thinking patterns people who suffer from psychological distress frequently engage in:

- All-or-nothing thinking, e.g., “I’m either a winner or a loser.”

- Catastrophizing, e.g., “If my partner leaves me, I won’t be able to live.”

- Ignoring evidence for positive interpretations, e.g., “I only passed the test because I got lucky.”

- Emotional reasoning, e.g., “I feel like a failure, so I must be one.”

- Labeling, e.g., “I’m a loser.”

- Magnification/minimization, e.g., “A mixed review means I’m incompetent. Positive reviews don’t mean anything.”

- Mental filter, e.g., “Because one person at the party didn’t like me, I must be a loser.” (Even if other people did like you.)

- Mind-reading, e.g., “She thinks I’m an idiot.”

- Overgeneralization, e.g., “I messed up the recipe. I can’t do anything right.”

- Personalization, e.g., “Susan canceled our plans because she hates me.” (Ignoring that she might have had another reason.)

- Imperative thinking, e.g., “I should never make mistakes.”

- Tunnel vision, e.g., “He’s such an idiot. He can’t do anything right.”

One of the central tenets of CBT is not to flatly deny these statements. Indeed, they’re often partially true, and it’s that grain of truth that allows them to take deep root in our minds.

Instead, the therapist encourages patients to begin to notice these automatic thoughts. Then, through a process of Socratic questioning, the patient assesses their validity. Patients are asked to give reasons why a belief might be true, and also offer reasons it might not be.

A friend not replying to a text message might trigger the thought, “She doesn’t like me. Nobody likes me.” But considering other possibilities, “Maybe she is busy?” or remembering that she helped you move last year and invited you to a party recently, can help you to question the validity of that belief.

Action Plans: The “B” in CBT

While cognitive therapy was initially formulated to focus on disordered thinking, it has since merged with behavior therapy, which focuses on the dysfunctional actions people take.

Consider anxiety. A socially anxious person starts to feel anxious when asked to present at work. All month, he sweats over the proposed presentation, finally asking his boss to find someone else to do it.

Avoiding his anxiety, however, has two major consequences:

- The relief he feels in not having to do the presentation reinforces his behavior. Like a rat rewarded for pressing a lever, the motivational part of his brain is encouraged to find ways to avoid presenting in the future.

- By not presenting, he never gets to see if his feelings about presenting were accurate. He may have believed he would have been humiliated, but he’ll never get disconfirming evidence that such an outcome was unlikely.

Action plans and behavioral experiments designed to test the validity of beliefs are central to CBT. These are especially important for depressed patients, whose illness makes even doing simple chores or self-care incredibly difficult. By taking small actions, you pry open a gap between the self-sustaining feedback loop depressive thoughts and inaction generate.

Does CBT Work if You Don’t Have Depression or Anxiety?

One thing that struck me while reading the research on CBT was how much of it seems relevant to healthy psychological functioning, in general, and not just extreme cases of anxiety or depression.

If you squint at it, a lot of the advice in CBT reads like something straight out of a self-help book: take action, even if you don’t feel like it; visualize your intentions; set goals; exercise; and build habits to strengthen your motivation. That might be because CBT is simply common sense (if so, then it’s surprising it’s not more widely adopted). But I also suspect that CBT-informed theories and language have leaked out into the broader culture. Anyone reading therapy-adjacent popular books will end up absorbing some of it.

Reading the categories of disordered thinking, I was struck by how often I could think of examples in my own thoughts: Reflexively blaming a lack of reply from a friend on a broken relationship (rather than busyness) or emphasizing the few critical emails I get over the overwhelming majority of positive ones. I don’t think of myself as depressed or anxious, but I can see the parallels between my thinking at times and those of Beck’s patients.

What’s The Active Ingredient in CBT? The C or the B?

As mentioned above, CBT, as a whole, is one of the most effective forms of therapy. It is the gold standard for a reason.

But CBT isn’t a specific technique. Instead, it’s a framework for thinking about psychological problems that incorporates many different methods. Exposure, mindfulness, hypothesis testing, self-acceptance, problem-solving, goal-setting and other ideas all fall into the CBT umbrella.

Thus, which elements of CBT underpin its effectiveness is still an open question. One debate concerns whether the active ingredient in CBT is the work of belief change—the noticing of automatic thoughts and subjecting them to a kind of rational analysis, or if it is direct behavioral change that makes CBT so effective.

Research on exposure therapy for phobias, PTSD, and anxiety, for instance, has found that exposure alone performs roughly as well as exposure plus cognitive therapy. Talking about why you shouldn’t be afraid may not be as important as simply exposing yourself to your fears and letting them subside.

Similarly, while depressive patients get stuck in disordered patterns of thinking, they also get stuck in patterns of dysfunctional behavior. Staying in bed all day, not exercising and failing to keep up with basic life tasks can make depression worse. Perhaps the value of CBT lies more in its ability to push people to take action, even if they still feel lousy.

Can You Self-Administer CBT?

Another question that percolated in my mind while reading about CBT was whether it is relevant to self-improvement. Nearly all of the research conducted has taken place in the context of formal therapy. While I did see some research involving informal or self-conducted CBT, it’s too scanty to deserve the same evidence-based label that therapist-conducted CBT deserves.

It’s a worthwhile question to ask because there’s a particular challenge in questioning your own beliefs. Socratic dialog with a therapist can help you uncover specific, maladaptive thought patterns and beliefs. In contrast, there is something almost paradoxical about questioning sincerely held beliefs; if you already knew a belief was false, you wouldn’t hold it in the first place.

Behavior change may be a more valuable locus of change for self-directed improvement. It escapes the rational belief paradox above, and behavioral experiments can expose you to new evidence that undermines flawed beliefs.

Still, given the cost and difficulty of obtaining mental health support and the fact that many people’s difficulties do not rise to the level of a clinical disorder, I think understanding the framework CBT presents can help us live happier and more productive lives.

_ _ _

Further Reading:

- Cognitive Behavior Therapy by Judith Beck

- Exposure Therapy for Anxiety by Jonathan Abramowitz, Brett Deacon and Stephen Whiteside

- A comprehensive review of the efficacy of CBT across various disorders.

- Comparing traditional CBT to “new wave” treatments (including mindfulness).

- A critique of the importance of belief change (versus behavior change). And a rebuttal.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.