When it comes to language learning, grammar gets all the attention. Most theories about second language acquisition focus primarily on how we acquire syntax—the way we put words together to form sentences.

Vocabulary, in contrast, has historically been outside of the spotlight. This is unfortunate. Research has shown that your vocabulary has the greatest effect on comprehension.1 A major difficulty students have in learning a new language is the sheer volume of new words.

Given its importance, I was pleased to encounter Stuart Webb and Paul Nation’s How Vocabulary is Learned, a research-based handbook for teachers that looks at how to deal with one of the central difficulties in becoming fluent.

How Many Words Do You Need to Know?

The first step in any journey is figuring out how far you are from your destination. How many words do you need to learn to be fluent?

Right away, this question runs into difficulty. How should we count words?

One way would be to count every distinct spelling in a set of texts. Except, this approach drastically overcounts. It would include regional spelling differences (e.g., color in the US, colour in the UK) as well as numerous grammatical inflections that are almost certainly not stored in the brain as separate words (e.g., difficult, difficulty, difficulties, etc.).

Instead, researchers usually prefer to count word families—which include not only distinct words, but also their related inflections, variations in spelling and derivations.

How many word families do you need to know?

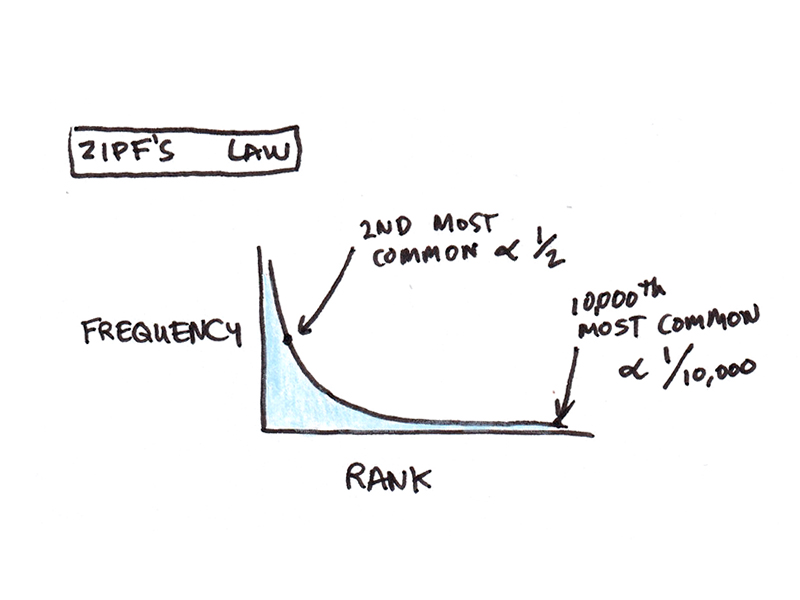

Here, we can take advantage of an empirical finding known as Zipf’s law. This law states that if we rank every word in a language in order from most-used (rank = 1) to next-most used (rank = 2) to least-used (rank = n), a word’s frequency of use is proportional to the inverse of its rank.

This means that the frequency of the second most common word would be roughly equal to 1/2 times some constant. In contrast, the frequency of encountering the 10,000th most common word would be roughly equal to 1/10,000 times that same constant. We would expect to see the second most common word 5000 times for each time we see the 10,000th one.

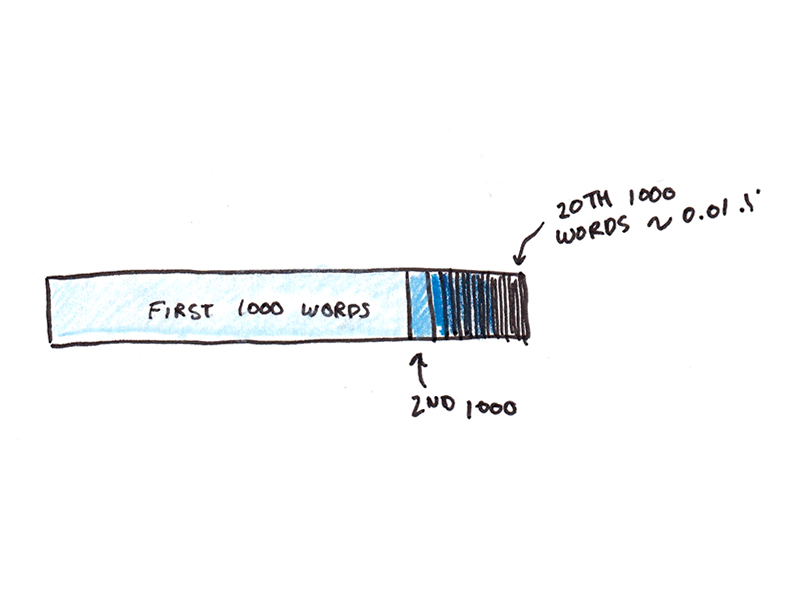

The first 1000 word families in English, for instance, account for roughly 85% of the words encountered (e.g., baby, cake, dad), and the next 1000 account for only 4.3% (e.g., background, accent). By the time you get to the 20th batch of 1000 words, they make up less than one-hundredth of one percent of the available words (e.g., abaya, chiastic).

Knowing just the first 2000 word families would cover roughly 80-90% of most novels, newspapers, conversations, television shows and academic lectures.

The upside of this finding is that you can quickly get to the point where you know most of the words being used.

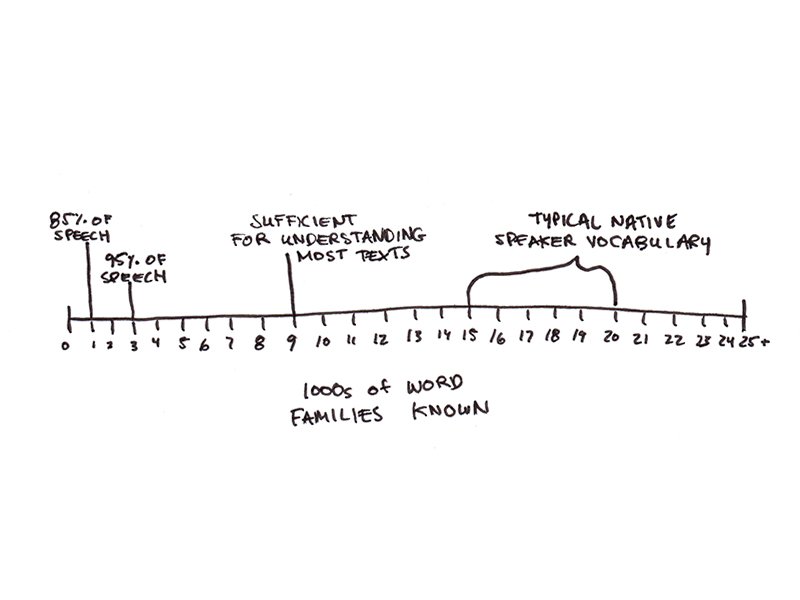

The downside is that low-frequency words are often essential for understanding what is being said. Native English speakers tend to know between 15,000 and 20,000 word families. Since most of those words occur increasingly infrequently, the amount of exposure needed to learn all of them properly can be staggering.

What, then, should a practically-minded language learner focus on? Webb and Nation suggest two goals might be important:

- Knowing 3000 word families “would allow learners to understand 98% of the words in most graded reading materials, as well as 95% of the vocabulary used in spoken discourse.” Knowing 95% of the words used is often considered the threshold for understanding, so learning the 3000 most common word families is a good beginner goal.

- Knowing the 9000 most frequently used word families, which include both low- and mid-frequency words, “equates to sufficient vocabulary knowledge to understand speech and writing,” Webb and Nation continue, arguing that “differentiating between the words before and after this point is useful.”

How Should You Learn Words? The Power of Extensive Exposure

When it comes to our native languages, researchers already have a pretty good idea of how we learn words, and it’s not through studying vocabulary lists.

In a celebrated series of papers, William Nagy, Richard Anderson and Patricia Herman found that school children add as many as ten new words to their vocabulary per day for several years.2

Maintaining such a pace with explicit teaching would be next to impossible, and yet native speakers not only learn this many words—they integrate them seamlessly into their actual language use.

Obviously, the process of learning words in one’s native language is not like memorizing definitions from a dictionary. It’s not as if native speakers are being assigned ten words every day to memorize. Instead, their extensive exposure to words in their environment lets them steadily accrete knowledge of new word meanings so that, averaged over long periods, they learn roughly ten new words per day.

This alone shows that long-term exposure to an immersive linguistic environment is enough for vocabulary growth.

However, native speakers also accumulate tens of thousands of hours of meaningful language input and use—far more than most people can achieve studying a foreign language!3

Should You Use Flashcards to Learn Vocabulary?

Extensive exposure is sufficient for vocabulary learning. Yet, given the huge quantity of speaking, reading, and listening time one gets with a native language, exposure alone may not be enough for the typical language student.

Flashcards offer a quick and effective way to acquire a large vocabulary, especially when the meanings of words can be readily paired with their counterparts in one’s native language. Spaced repetition systems, like Anki, also offer the opportunity to store large libraries of cards and allow reviews to be queued so that studied words won’t be forgotten.

However, flashcards for single words also have disadvantages. Learning a word in isolation can cause you to miss its connotations or usage in particular contexts. Cards that focus on a word family may also omit some of the possible grammatical modifications of the word and their meanings.

Cautioning on the exclusive reliance on flashcards, Webb and Nation write:

“It is also important to remember that learning with flashcards is only one step in the vocabulary learning process. … Flashcards should be supplemented with plenty of meaning-focused input that includes the target words to provide models for how these words are used, and meaning-focused output that provides opportunities to use them.”

Other Advice for Learning Words

Webb and Nation review some other advice on learning vocabulary:

- Words with similar meanings should be taught on separate days. Teachers typically cluster words by categories (e.g., days of the week, colors, occupations, etc.), but research indicates this may be unwise. Students show greater interference when items with similar meanings are taught in the same sessions.

- Graded readers can accelerate implicit learning. To successfully guess the meaning of a new word from its context, we need to understand between 95% and 98% of the surrounding words. This is difficult to achieve with native-level materials. Graded readers, which deliberately limit vocabulary, can be beneficial here.

- The rate of vocabulary acquisition depends on student enthusiasm and aptitude. Webb and Nation suggest that a dedicated student might acquire 400 word families per year, assuming they are exposed to the words in various contexts. For narrower word learning, such as from flashcards, more words can potentially be covered in a similar time frame.

- Learners should spend time on all four pillars of language learning:

- Meaning-focused input. This includes conversations, books, films, television and other media that you attend to primarily for their meaning. Input provides the raw data for learning new words and enriches the contextual associations of words studied deliberately elsewhere.

- Meaning-focused output. Speaking and writing are more difficult than simply understanding particular words from input, as using words correctly requires a more precise knowledge of each word and its meaning.

- Language-focused learning. This is the deliberate act of memorizing words, studying flashcards, or receiving explanations about word meanings. Webb and Nation argue that this should account for ~25% of the time spent learning a language.

- Fluency development. Finally, attention should be paid to activities that speed up the understanding and production of words already known. Familiar materials that enable quick reading or conversations on familiar topics may not be needed to build new vocabulary, but they reinforce what was learned previously.

Footnotes

- Laufer, Batia, & Donald D. Sim. “Measuring and explaining the reading threshold needed for English for academic purposes texts.” Foreign Language Annals 18, no. 5 (1985): 405–411.

- Nagy, William E., Patricia A. Herman, and Richard C. Anderson. “Learning words from context.” Reading research quarterly (1985): 233-253.

- It’s not entirely clear what cognitive mechanisms underlie this learning. It’s possible that we learn the meanings of words implicitly through their contextual associations. But it’s also possible that conscious efforts to puzzle out the meaning of words play a role, too.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.