I’ve been thinking a lot about habits lately. The students in my Foundations course are getting started with their daily fitness habit, and this has given me a lot of insights into the real barriers people have in creating habits that last.

The simple way of thinking about habits is as a cue, followed by a response. So, if you’re trying to start exercising, you might think of a habit as:

CUE: I finish work for the day → RESPONSE: I go to the gym.

CUE: I wake up in the morning → RESPONSE: I go for a run.

CUE: I finish putting the kids to bed → RESPONSE: I do a home workout.

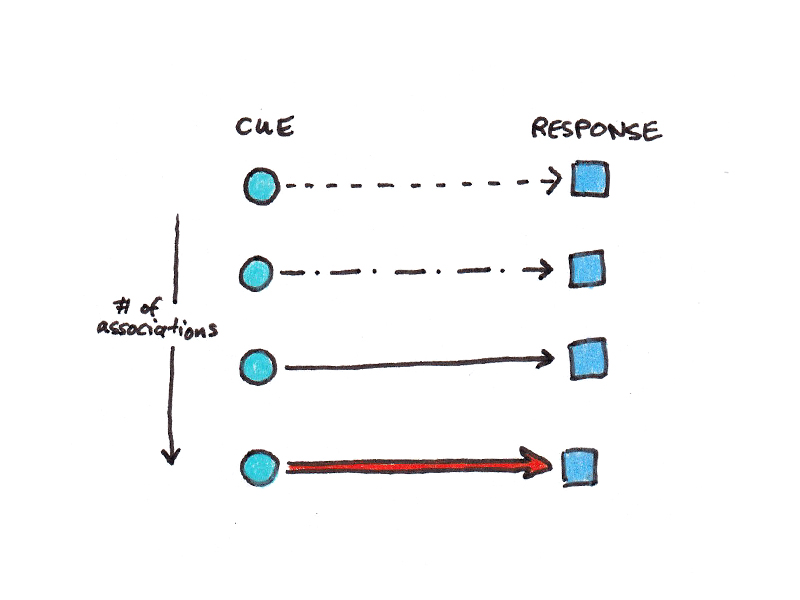

Over time, these cue-response relationships strengthen. This makes deciding to exercise more automatic and effortless over time. If you always work out right when you wake up, it may feel weird at first, but after three months, it feels totally normal.

This is the principle of classical conditioning, first discovered when Ivan Pavlov realized his dogs would salivate when hearing the dinner bell, even before the food the bell predicted showed up. Classical conditioning is ubiquitous in the animal world—even sea squirts do it—thus, it is as close to a universal principle of psychology as one can get.

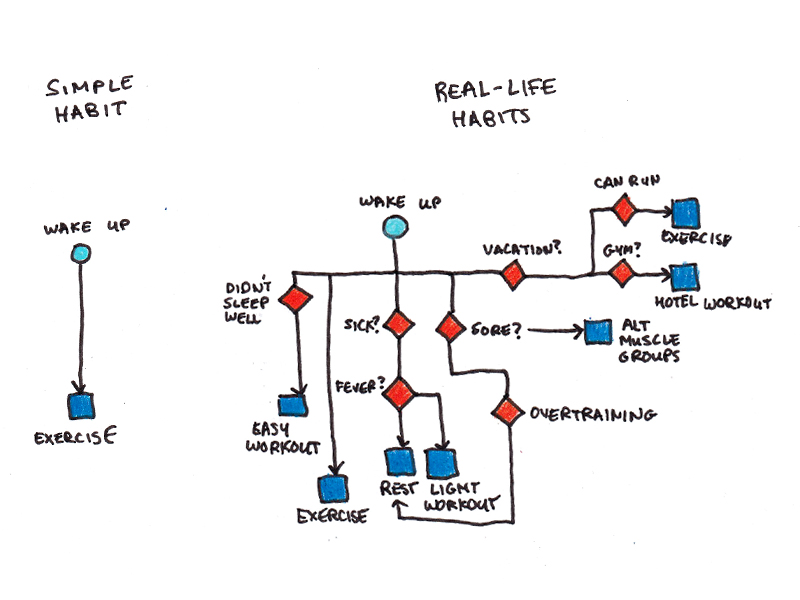

At the same time, anyone who has actually started a new habit, such as exercise, knows that real life isn’t so simple.

The Problem with Habits in Real Life

The cue-response relationship is a good primitive mental model of habit formation. But real life is a lot more complicated.

For one, a lot of our “habits” aren’t consistent cue-response relationships. Even something as simple as daily exercise has an enormous amount of complexity:

- What do you do when you’re on vacation?

- How do you handle work overrunning into your workout slot?

- What about when the gym is closed for repairs? Your car breaks down? Your running shoes wear out and you need to buy new ones?

- What about when you’re sore from one workout and need to do another one?

And this is for a relatively “simple” habit like exercise.1 Most foundations we want to improve involve much more complicated habits.

Healthy eating, for instance, is much more complicated than fitness. Instead of a simple cue-response, eating well relies on building myriad habits: What do you eat for breakfast? Sack lunch or eating out? How do you handle holiday treats? What about office happy hour?

Despite these complexities, many people manage to form effective, lifelong behavioral improvements in these areas. It’s probably not through simply strengthening a cue-response association, so what’s really going on?

Habit Formation as Problem Solving and Skill Learning

Psychology has another mental model we can look at for behavior change: the science of problem solving and the acquisition of expertise.

Problem solving is all about dealing with unique circumstances in appropriate ways. Is the way forward a dead end? Find a detour. Did something interfere with your plan? Throw it out and draft a new one. Unlike classical conditioning, problem solving is a capacity unique to more complex organisms, reaching its highest expression in humans. With it, we don’t learn only through cue and response, but can form plans, strategies, intentions and alternatives.

As we continue to solve problems, we acquire expertise. Expertise is, in many ways, an elaboration of the cue-response associations possessed by simpler organisms. As we repeatedly encounter a variety of different scenarios, we develop well-worn solutions.

But expertise is more than just a collection of habits. We also have ideas and mental models that guide our actions. Seeing the car in front of you brake suddenly and slamming on your car’s brakes is a habit. Recognizing that you’re driving at highway speeds and giving the car ahead of you more room in case you need to brake is expertise.

Learning a New Habit

What does this somewhat altered perspective say about the habits we want to form to sustain our lives? I think it suggests that something more sophisticated is going on when we “condition” a new habit. Yes, we do form cue-response associations, but we also do more than that.

First, we set goals and intentions. We choose to set higher standards to hold ourselves accountable. Problem solving is goal-directed—we decide a kind of behavior we want to have in our daily routine, and we hold that intention in mind as we try to find ways to solve it in each set of unique daily circumstances.

Second, we create strategies. Strategies are more than just cue-response associations. For one, they’re conscious. “I’ll wake up in the morning to exercise” does establish a cue-response, but it also encourages you to be mindful of your previous intention when you wake up.

Third, we learn to deal with specific problems. As our “conditioning” progresses, we deal with unique challenges and figure out custom solutions. What do you do when you’re tired? Sore? Sick? On vacation? When the gym is closed or the weather is bad? There are no “right” answers, but if you solve these subproblems successfully, you’ll improve your ability to stick to the intention you set and the strategies you articulated.

The cue-response framework is helpful, but sometimes it can enforce an overly rigid perception of what is going on when we successfully implement behavior change. The reality is that making a new behavior part of your life is fundamentally a learning challenge—a process of successive problem solving until you have found ways to resolve most of the issues you face in your daily life.

The result is not one habit, but many. Not a cue-response relationship, but a collection of flexible strategies that deal with most scenarios reality throws at you. When you’ve done that, you’re acquired a kind of expertise—not of a subject, but of yourself.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.