A reader recently referred me to this project to break into the top 250 table tennis players in the UK in one year.

What happened? He failed. In his own words:

“The challenge ended a week ago and I am still nowhere near the top 250. I wasn’t even good enough to get an official ranking. Worse it was the most public failure ever – I told everyone I met what I was doing and posted it all over the internet. And now everyone has seen me fail!”

As someone who does ambitious, and some would say, arrogant, projects, I sympathize. Any learning goal suffers under the problem that you also lack meta-knowledge about the goal before you start. The only way to get that knowledge is to try.

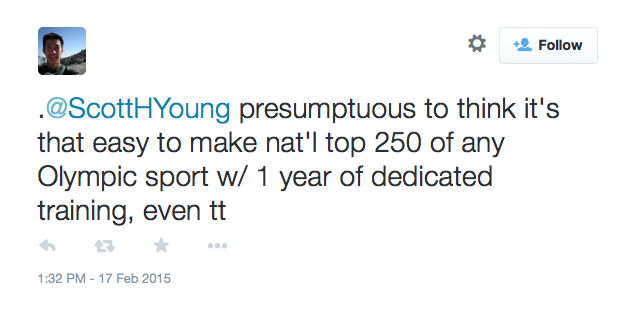

But then I got this tweet from a reader when I mentioned the project:

Is it presumptuous to think you can get into an elite level for a sport in only a year’s worth of training? Of course. Is it arrogant to think you can outdo people who have been training for decades? Definitely.

But who cares?

I hate the attitude that we’re not allowed to set ambitious goals, just because they might be unrealistic or “offend” people that worked very hard.

Sam, our table-tennis-expert attemptee, says he was “naive” and failed to realize how difficult the goal would be. Doing an ambitious, public challenge has a lot of risks. That’s one of the reasons I usually spend almost as much time researching my year-long projects as I spend actually doing them.

But even if you plan excessively and try to account for every variable, you’re still going to make mistakes. I would say my challenges were both largely successful, but even with the intense planning I did there were still things I wish I had done differently:

- I wish I had hired official graders instead of self-grading for the MIT Challenge. The relatively objective nature of the content along with solution sets and grading rubricks made me dismiss this idea as too costly/timely in the research phase. But now I realize that it would have added greater legitimacy to the project.

- During the year without English, I did do one standardized exam: the HSK for Chinese. However, I wish I had done them in all four languages, since it would have been easier to specify exactly what level was reached in the period of time.

But such problems, obvious in hindsight, weren’t clear ahead of time. Perhaps the audacity of trying to break into the top 250 for an Olympic sport should have been clear from the beginning. But then what about Joshua Foer, who didn’t just enter the elite, but got the first place in the US Memory Championship with only a year of training?

In fact, its just as easy to suffer under the opposite problem: setting goals which are too easy. I shied away from making any specific claims as to what level of fluency Vat and I would reach during our stay in each country. But that also meant we didn’t prepare for any formalized assessment other than my HSK test. Here the problem wasn’t too much boldness, but too little.

When the only thing at stake is your pride and a little bit of time, I say it’s better to make errors of boldness than of caution. I’d rather try a bit too hard and fail, than wonder about what I might have been able to do if I had really tried.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.