I often write about learning faster and learning more efficiently as if they were the same. And in many cases, they are. If it would normally take you 100 hours to learn a subject, and by cutting waste you can get that down to 50 hours, you’ve learned faster and more efficiently at the same time.

But sometimes learning faster and learning efficiently don’t mean the same thing.

Consider two approaches to learning calculus. One, you take a week, and spend twelve hours a day studying. The second, you take four months, but you only spend an hour each day. You’ve invested roughly the same number of hours, so assuming you have the same knowledge at the end, the two approaches were equally efficient (In fact, the slower one is probably more efficient due to the spacing effect, but I’ll get to that later), but the one-week approach is much “faster” than the second in terms of the total time elapsed to learn calculus successfully.

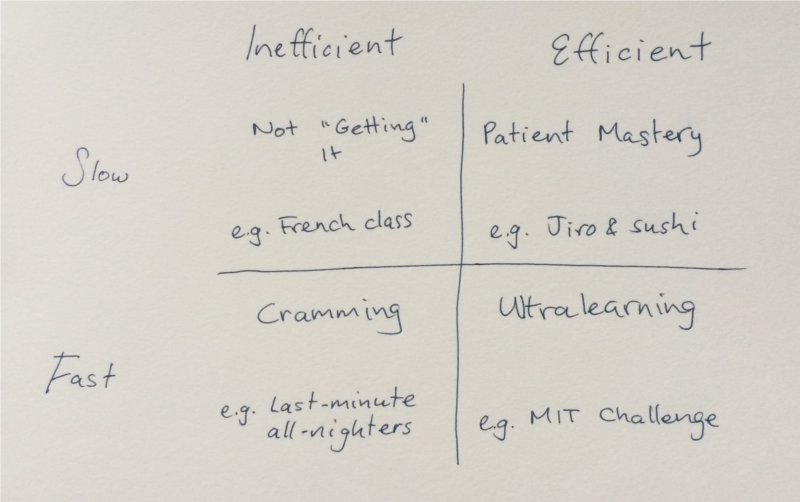

You can actually map out these two dimensions of learning strategy and see the results they imply:

SLOW / INEFFICIENT – Not “Getting” It

Here we have things like some French classes where you spend a few years but can’t hold a conversation in French. Math classes where you put in hundreds of hours but can’t remember it a few years later. Many learners are stuck in here for some subject, either because of lousy instruction, poor motivation or inferior techniques.

FAST / INEFFICIENT – Cramming

Here we have studying the last night to quickly memorize things just long enough for the final exam. We have skimming books to hopefully pick up a few details rather than taking the time to really absorb the message. Learners can get stuck here because of desperation, or because they aren’t aware of how short a half-life their knowledge has.

SLOW / EFFICIENT – Patient Mastery

This process is one of slowly accumulating knowledge through ironclad habits. The difficulty with this quadrant is that rewards come slowly, so the emphasis must be on process. It’s also easy to fall into stagnant routines, so a balance needs to be struck between habits and deliberate practice. For examples of this, look at Sukiyabashi Jiro or Olle Linge.

FAST / EFFICIENT – Ultralearning

This process is one of deep, aggressive learning. I’d like to think the MIT Challenge and Year Without English were of this sort. I hesitate to label this category ultralearning, because I believe a slower approach can still qualify if it matches other characteristics of ultralearning. The difficulty with this approach is making the commitment to focus sufficiently, and long-term maintaining the knowledge after the initial intensity is gone.

How Should You Learn?

My feeling is that, if your goal in learning is to actually learn things (as opposed to just learning for entertainment), the inefficient approaches can be safely ruled out. Now the question goes onto whether you should try to learn via an intense, short-term burst, or through a very patient long-term habit.

Benefits of Slowness

Slowness has a number of benefits to learning, provided it’s done efficiently. The foremost of which is the power of the spacing effect.

The spacing effect is a robust effect in memory research which shows that spreading out the time spent learning improves long-term memory performance. In other words, spending 10 hours learning a set of facts in one day will have worse performance than spending those ten hours over ten days.

This means that, over a long period of time, a very slow approach to learning as an efficiency edge over learning faster. Somewhat fewer hours to get the same result.

Another benefit of slowness is that a slow learning process can be more easily accommodated in a busy life. Taking 10+ hours out of your schedule each week is a lot harder than taking only one or two. So if you restrict yourself to only taking on large, intense projects, you may not be able to learn some things.

Benefits of Intensity

Learning intensely also has some benefits I’ve found from my own experience. The first is that sometimes the quality of practice cannot be easily replicated at a lower level of intensity.

Consider language immersion. The effort involved to do complete immersion, without using your mother language, is considerable. But compared to how much high quality practice you get, it’s actually fairly low. Put another way, if I wanted to have 500 hours of high quality practice, it would be much easier to invest it in a small number of intense immersive bursts, than constantly switching between languages the way you would for a class.

Sometimes barriers for entry make intensity the way to go when starting to learn something new, even if you eventually switch to a slower approach. When I’m learning a new programming language, for instance, I need to focus. There’s a lot of frustration starting with a new language, and if I spread that over months, I’m much more likely to procrastinate on learning.

Learning intensely also has benefits in that you can more quickly see results. These results feed your motivation and make the project more enjoyable to pursue. If you learn too slowly, sometimes it can feel like success is so far away it isn’t worth pursuing.

My Current Approach

In my own life I learn some things slowly and other things fast. I’ve noticed a couple trends in my own practice which may be useful for you as well:

- When I’m starting out, I like to learn intensely. This builds competence and motivation quickly and pushes through frustration barriers.

- Once I’ve reached an intermediate level, and beginner gains are harder to come by, I like to learn slowly. This is the stage I’m at with my languages and computer science knowledge.

- After I’ve had an intense learning project, it’s good to follow it up immediately with patient habits. This attenuates problems with the spacing effect and keeps the knowledge at the surface.

- When I know I can’t focus on a project with much effort, but it’s not frustrating to me, I start off with a slow approach. I’ve been doing this with the cognitive science reading materials.

What do you think? Beyond trying to learn efficiently, how do you approach things? Do you prefer to focus yourself on a single project and improve rapidly, or do you spread things out over time? Do you feel you could benefit from mixing the opposite approach into your strategy?

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.