As someone who writes advice for a living, I’m always interested in the ways advice works, how it gets distorted and what the typical advice-receiver can do about it.

Recently, I came across some research that suggests a new way advice-givers aren’t being totally honest with you: paternalistic advice bias.

Here’s the abstract, from the journal article:

“Despite the near universality of the maxim that one should treat others as one ought to be treated, even well-intended advisers often advise others to act differently than they choose for themselves. We review several psychological factors that contribute to biased advice. Absent pecuniary motives to the contrary, advice tends to be paternalistically biased in favor of caution. Policies that would intuitively promote quality advice — such as making advisers accountable, taking advice from advisers who value the relationship, or having advisers disclose potential conflicts of interest — can perversely lower the quality of advice.”

Biased Advice Leads to Excess Caution

The idea here makes intuitive sense. An advice-giver, whether its someone giving advice in the form of a blog article, or a friend or mentor suggesting a course of action, is not merely transmitting what they know from their own experience.

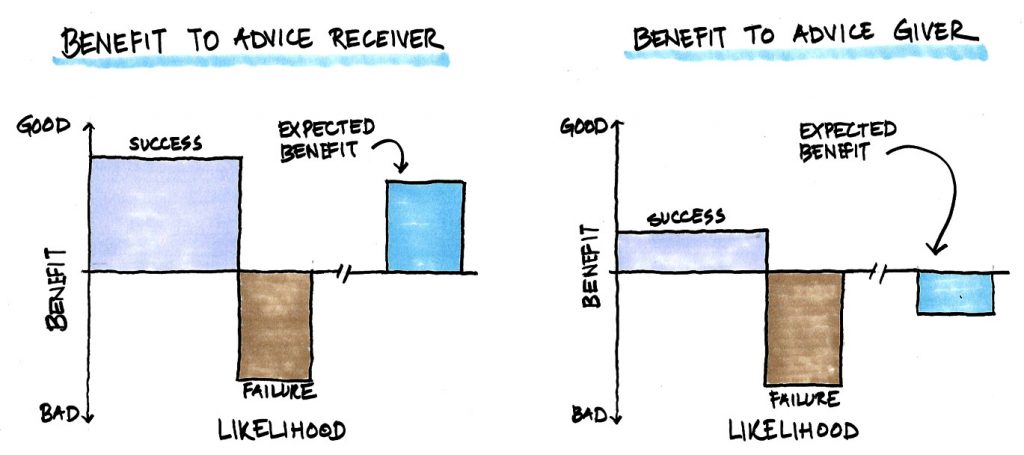

Instead, there’s a subtle cost-benefit calculation that has to be done when giving advice. And here, there’s a big problem: the flaw of bad advice. If you give someone advice that ends up going disastrously wrong, you might get blamed for that. And the blame, reputationally speaking, might be worse than the benefit of helping you win big.

To use a purely hypothetical example, imagine you have to ask a trusted friend for advice about quitting your job to start a business. Suppose this person knows, privately, that there’s a 30% chance you’ll be a big success and 10% chance you’ll lose quite a bit of money, with the remaining 60% of the time the change is relatively neutral.

Now, if this trusted friend were doing the calculation themselves, they might value a 30% chance of big success more than a 10% chance of a financial blunder. So, privately, that person might go ahead with it anyways.

However, as an advice-giver, they may recognize that in the chance you’re successful you might only thank them mildly for encouragement, a small benefit, but if they go bankrupt they may blame you for goading them on, causing deep resentment or worse. As such, you may advise caution if this person is really on the fence about the decision.

Is There an Anti-Effort Bias in Some Advice?

This finding about advice was risk-aversion, but I can see how it could possibly extend to effort-aversion as well. If the effort itself forms a type of risk, you might caution a middle-route of reasonable effort as opposed to the high-intensity path you might personally take.

I may be over-generalizing the findings here, but this also makes intuitive sense to me. Expending a lot of effort is itself a kind of cost. Just as I could imagine being cautious advising someone to invest hundreds of thousands of dollars in an uncertain investment, I might also imagine being cautious telling someone to invest thousands of hours of effort in a project which isn’t guaranteed to work out.

This suggests to me the possibility that increased effort may be dissuaded against if it constitutes a greater risk.

Alternatively, if effort mostly guarantees success, then more effort would reduce risk and be (perhaps) overly recommended. How this affects advice might depend on the reliability of results after effort. People may recommend working hard at a new exercise plan to get in shape, which is a low-risk move, but not recommend working hard at becoming an actor or actress, which is high-risk.

Anti-Effort Posturing

It’s not related to the study mentioned earlier, but another plausible way advice can seem to reduce the emphasis on effort is when the person who is successful has an incentive to downplay their own effort invested.

This bias doesn’t seem to be one-sided. I think we can all think of situations where people have exaggerated the contribution of their personal efforts (such as the son of a U.S. president boldly claiming to be a self-made man). Others are humble and dismiss the idea that their (very obvious) hard work had anything to do with their successes.

Most people tend to attribute this bias to personality. Some people are braggarts who like to champion their hard work and effort, when they really don’t deserve the credit. Some people are modest and gracious and would rather have circumstances or other people get the acclaim.

While personality may be a factor, I prefer to see it another way. People try to maximize their appearance. Sometimes, claiming to have invested a lot of effort makes sense, especially if it can distract from less praiseworthy causal factors in success such as connections, wealth or inheritance.

However, sometimes claiming to have invested a lot of effort makes you look worse. You would appear more magnanimous by suggesting luck and feigning humility. In some endeavors, suggesting raw talent or intelligence is seen more highly than investing a lot of effort. Presumably the latter implies you made different choices, and therefore have different values, which can sometimes be a source of distrust or resentment itself.

My own experience has shown that in my personal life (less so professionally) there’s a strong social incentive to downplay effort. Being busy and overworked is okay (that’s circumstances), but one must be more careful advertising a self-inflicted ambition that requires immense effort (that’s different values).

Many people I’ve talked to who have succeeded at ambitious projects speak similarly, saying that, while working on such projects, they’re often given a rather uncomfortable reception from people who don’t exactly look up to their intense efforts. It seems weird, forced or unnatural, and they often politely question why this person would bother putting so much effort in.

What This Means for Advice

This all suggests to me, at least, that there’s a large possibility of a fairly invisible layer of people around you putting in a lot more effort than is deemed socially reasonable for the pursuit they are after, and often succeeding at it too.

Advice, especially when passed from person-to-person, may be overly risk-adverse, and encourage low-effort strategies for pursuits where success is uncertain.

The combination of these effects, if one doesn’t see through it, can be to fatally underestimate the intensity and effort successful people invest in their goals which inevitably leads to them doing well.

Ultimately, I think the magnitude of this effect will depend on how big a role these underlying factors play. More certain goals will probably show less anti-effort bias. Goals which are more conventionally appropriate to show extreme ambition in (athletics, academics in many settings, high-effort/high-status career paths such as medicine, etc.) will likely show less of this bias. In these cases, the bias might even reverse with successful people actually working *less* hard than you think.

However weird, risky goals like starting a new business, ultralearning projects and high-variance career paths, might have enough of the opposite bias that success for many people is inhibited simply because they don’t realize how hard successful people are actually working at those goals.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.