Nobody likes a critic. The colleague who stomps on your suggestions in the meeting. The reviewer who says your work is terrible. The high-school teacher who said you’d never make it.

The standard advice is to just ignore your critics. March forward bravely and prove them wrong. Critics are envious, bitter or evil.

I see it differently. Not only are your haters not the enemy, they’re necessary. Even when they aren’t out to help, you need to live in a world where they exist.

Why Critics aren’t the Enemy

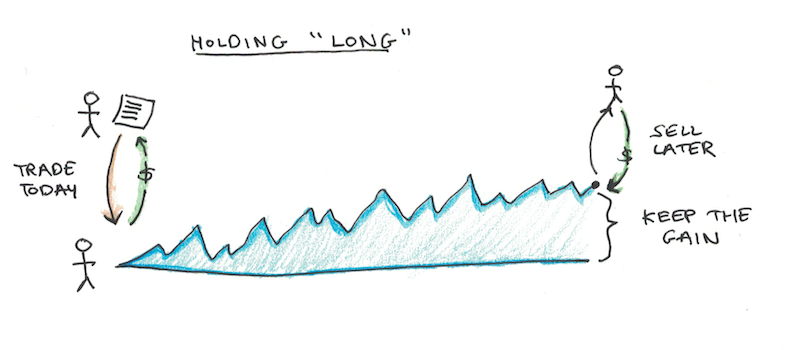

In investing, it’s possible to hold a stock in one of two positions. Long or short. Long means you’re invested in the asset, if the company does well, so do you.

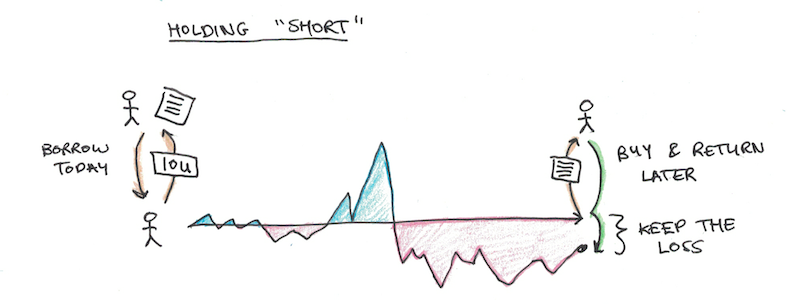

Short-sellers, in contrast, borrow the stock they don’t own, with a promise to pay for it later at a certain price. Instead of benefiting when a company does well, they win big if the company goes down.

Because they win while others lose, a lot of people don’t like short-sellers.

However, as anyone with a background in economics can tell you, short-sellers are vital. Without them, it’s only possible to bid a stock up with information, not down. Bubbles are common because the same group of enthusiastic people ramp up prices, without any way for the skeptics to cool things off.

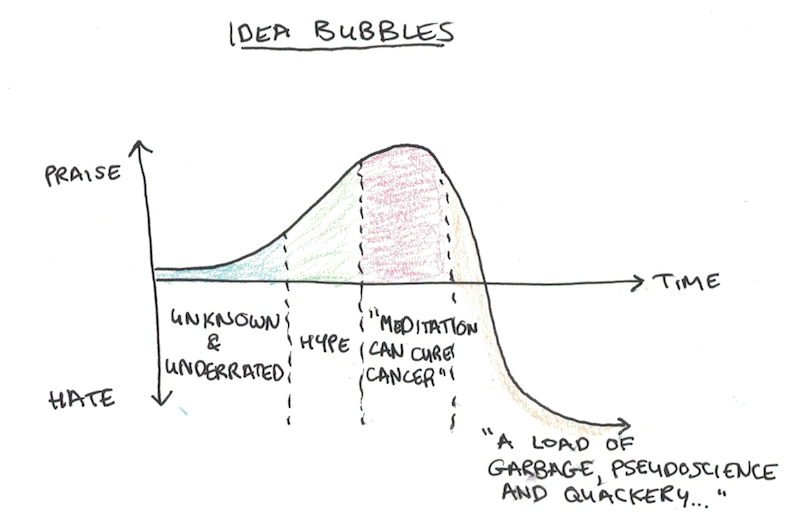

Ideas are like stocks and your critics are like the short-sellers. They prevent your ideas from getting overvalued, of getting over-hyped until they collapse.

Why You Need Your Haters

You want to live in a world of work, ideas and performance where your efforts are valued appropriately. Too much criticism and negative feedback is bad, of course. But so is too much praise.

Many ideas risk becoming over-valued when their hype overreaches their true value. I’m a big fan of ideas like deliberate practice, growth mindset and mindfulness meditation. But these ideas have also been stretched perhaps beyond their useful domain—supposed panacea. When those promises inevitably fail, the backlash may have people abandon what was good about them.

The better view is probably in-between—that these ideas are useful, but that they have limitations and drawbacks as well.

My Experience with Critics

I’ve gotten a wide variety of reactions from my own work, such as the MIT Challenge. On the one hand, I’ve gotten attacks from MIT students who don’t like my presumption, or those experienced in the field who dislike the way I ran my challenge. Although I don’t always agree with all the details of their critiques, I value the fact they exist.

On the other hand, however, it’s also not true that my biggest fans are always correct. Despite my efforts at clarity, I’ve also had people ask me how I got MIT to give me a degree (no formal recognition from MIT, degree or otherwise), or believing that I’m now a master at professional-level programming (most of my classes were in math, I didn’t even do a web programming class, for instance).

While I’d hope that people see my projects the way I do, the harsher critics also balance the fans. Without both, there would be a risk of perceptions of my work expanding beyond what is correct until it pops later.

While it’s not always fun to be criticized, those who dislike your work, force you to be more rigorous, honest and careful in what you do. It’s possible to pay too much attention to this, of course, and have your work become a reaction to your biggest detractors. However, at the same time, it’s possible to pay too little heed to this and have your work become full of glaring holes that only your most ardent fans will ignore.

How to Think About Your Critics

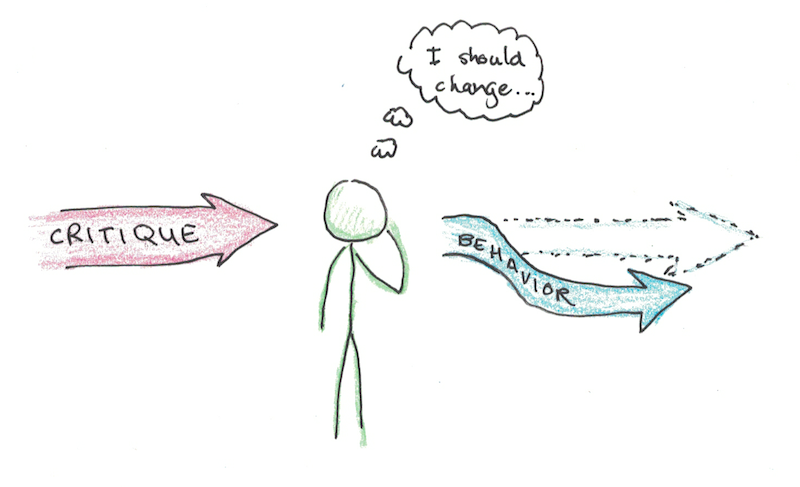

When you get criticized, whether it’s at work, from a friend or from a stranger you don’t even know, I think there’s a few possible reactions that are useful:

1. This is useful information, and I’m going to make a change.

The first way to react is to use the criticism. If it was constructive in some way, pointing out a flaw in your work that you can remedy, this is the best possible outcome.

Sometimes the change won’t happen immediately, but you’ll be able to keep the critique in mind for later. One of the criticisms I got for the MIT Challenge was self-grading the exams. This was unavoidable—I didn’t have the money or connections to hire qualified graders, so the best I could do was mark them myself and upload them so others could see/evaluate.

However, I did keep it in mind, so when the time came to do my language learning project, and I wanted a measure of objectivity for my Chinese progress—I opted for a standardized language exam (in this case the HSK 4).

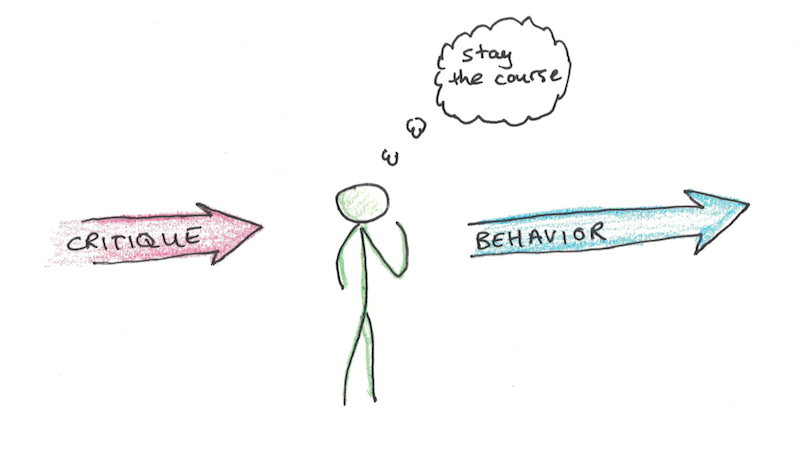

2. This specific criticism is unhelpful, but I should be aware it exists.

Sometimes the critics are wrong. They dislike your work for things you cannot change. Alternatively, they may dislike you for reasons different than the ones they attack you for, so pleasing them is only going to go down a losing path.

One critic of my Year Without English, said that since I was still writing in English (and talking to family back home, in English), it wasn’t “true” immersion, and therefore didn’t count. In this case, I completely disagreed. I don’t think going from the level of immersion I had, to the one he expected, would have made much difference to overall practice time, while making my life significantly harder.

Even cases like this, I think being aware of criticism can help you feel out reactions to your work. If you’re going to do something that gets a lot of criticism versus little, you will approach it differently. This kind of bulk feedback can be helpful, even if you’re not going to follow your haters’ advice.

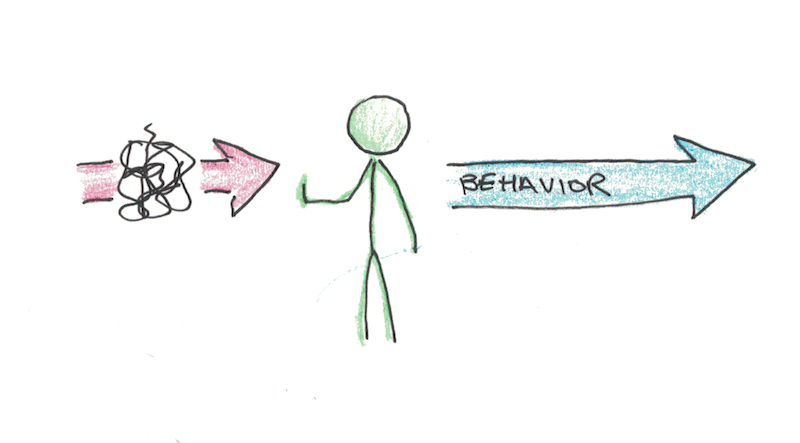

3. I can ignore this criticism, but it still serves a broader purpose.

Finally, I can think of feedback that’s so negative or debilitating that you’re better off ignoring it entirely. Someone who is aggressive in their dislike of you, for reasons you can’t change or are unwilling to, can make it harder to work and be motivated.

In those cases, I think it’s fine to tune out people who dislike you. You don’t need to read every poorly-considered insult of you and your efforts.

But at the same time, these are the inverse of the people who make poorly-considered praise. These are the people who react viscerally to you in a negative way, just as others may react in a positive way. While they may not be useful to you, they may work to make the balance of ideas more accurate in the long-run.

If you can see your worst detractors in this light, I think it’s a lot easier to accept and acknowledge them, even if you won’t agree or acquiesce.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.