Feedback is essential for learning. Whether you’re studying for a test, trying to improve in your work or want to master a difficult skill, you need feedback.

The challenge is that feedback can often be hard to get. Worse, if you get bad feedback, you may end up worse than before.

In a systematic meta-analysis of the literature on feedback interventions, researchers Kluger and DeNisi find that in over one-third of cases, the impact of feedback was actually negative! This means that finding good feedback is essential if you want to learn better.

What Kind of Feedback Should You Get

Good feedback has the following qualities:

- It provides information about the task you’re trying to improve on. “What if you tried it like this…” is better than, “Oh wow! You’re so smart!”

- It doesn’t have too much noise. If responses to your work are all over the place, it can be hard to figure out what to do with that information.

- It motivates you to work harder. Negative feedback, particularly if there’s nothing you can do about it (“You’re ugly!”), can remove your motivation. Lowered motivation can hurt more than added information, especially if you’re not 100% committed to your task.

The best kind of feedback tells you exactly what you need to fix to improve. Although this corrective feedback is great, it often isn’t available.

Pretending you have corrective feedback, when you really just have the subjective opinion of someone who isn’t sure how to help you, can be dangerous since you may actually get worse.

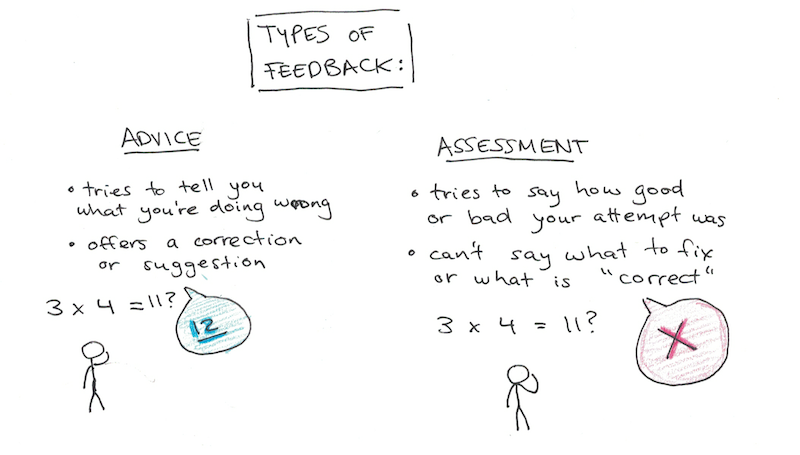

Is the Feedback Advice or Assessments?

Here’s a useful way to process it. If the feedback is telling you whether you’re doing something better or worse, ask yourself:

- Does the source of feedback matter for my purposes? Asking someone if they’ll buy something, when they aren’t your target market is a disaster. Bad feedback can be worse than no feedback.

- Can the source of feedback actually offer evaluations? A person reading your debut novel may be able to tell you whether they liked it or not. But unless they have serious publishing experience, they probably can’t tell you whether or not it will sell.

- Is the feedback noisy or consistent? A friend of mine who does a lot of public speaking told me that he only trusts audience feedback once it starts to get consistent critiques. When the feedback is all over the place, he knows the speech needs too much work for their thoughts to be reliable about what’s wrong with it.

Compare this now to feedback which offers advice. This isn’t merely telling you whether your work is good or bad, but also what you could do to improve it. Experts or “correct” answers can offer this kind of advice. A big mistake is relying overly on opinions of other people as being the truth about what’s good and bad with your work, especially if those people aren’t experts themselves.

How to Get More Feedback

Once you’ve learned to spot what kind of feedback you’re getting, and whether it’s good enough to pay attention to, you now need to find out how to get more of it. Here are a few ways you can try:

1. Find a peer group for practice.

As I write in this article, the right environment can make all the difference between stagnation and mastery. Much of this is through the influence of peers. If you have peers who can both offer feedback and open you up to new techniques and methods to improve you’ll learn much faster.

You can find groups like this in-person through websites like meetup.com, professional organizations and conferences. You can also find them online through dedicated forums such as Stack Exchange or subreddits.

2. Do more of your work publicly.

This blog actually started as a feedback-gathering project. Originally I thought I wanted to make some games/software with a personal development theme. The program would have some articles embedded, and because I wasn’t used to writing, I thought writing a blog would help me get some feedback to improve.

It turned out the games I made were terrible, but the articles ended up being interesting enough that I focused solely on writing. Doing public work has a big benefit in that feedback allows your skills to improve quickly, while also opening you up to opportunities that may not accrue to private work.

3. Take a class with an expert.

Sometimes you can pay for feedback from experts. Art classes, carpentry studios or even online classes can allow you to get experts to critique your work.

These sometimes cost money and they’re more work. But the advice can also be invaluable. Having someone with an expert eye pour over your work and give you an evaluation can be well worth any price you have to pay to attend the class. Even if you think you already “know” what they’re going to teach.

4. Source objective metrics for your work.

Metrics can’t tell you what to improve, but they can give you a more objective sense of how well you’re doing. Too many people avoid metrics entirely, sticking to purely qualitative dimensions of feedback which often ignores the deeper, quantitative signal.

How many people are reading your articles? What score do you get on the practice tests? What’s your free-throw percentage? How many people pre-order your product? All of these signals can be cultivated and used to augment other feedback you might receive.

5. Trust your own gut.

A final suggestion for feedback is simply to get it from yourself. You are the best evaluator of your own work. Training yourself to see your work honestly and asking yourself what you like and dislike about your own work is a powerful source of feedback.

For many projects I undertake where outside feedback is minimal, I rely on self-generated feedback. I try to write, make or do something. Then I ask myself what I think about it. If I like it, I do more. If I don’t, I try to figure out why too.

Sometimes this self-generated feedback will be distorted, like a fun-house mirror where you are overly critical or self-congratulatory. However, if you get a mixture of outside feedback, you start to sensitize yourself to know what is good and bad in your own work as well.

Be Willing to Listen to Feedback

Often it is not the information itself, but our emotional reaction to it, that causes us the most problems with feedback.

Authors who put their work in a desk-drawer instead of in front of an audience, because they aren’t “ready.”

Students who shy away from taking the practice exam because they’re worried they’ll fail.

Public speakers who choke on stage, because they’re worried about hearing crickets.

This emotional reaction is not always easy to deal with, but the best approach is to just push yourself to get a lot of feedback and get it early in your work. This takes the sting out of getting it later and forces you to see it for what it is: information to help you improve, rather than an assessment of you as an individual.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.