There are two kinds of people you can look up to. The first are the all-encompassing mentors. The people whose careers are ahead of yours, who have businesses with ten times your revenues, with fancier titles and more impressive accomplishments on their resume.

These kinds of mentors are great: they inspire, motivate and can offer wide-ranging advice.

However, often these mentors are more difficult to get substantial time with. Everyone would like to be hand-coached by the CEO, but there are more entry-level upstarts than C-level executives, and so, most people won’t get this kind of treatment.

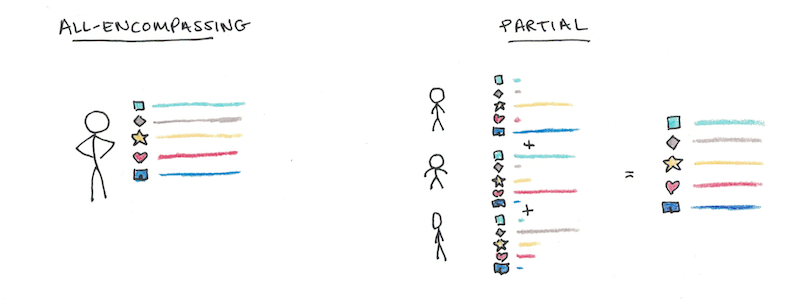

Instead, I recommend most people focus on another kind of mentor—a partial, limited mentor. Someone who has clearly mastered something important, further than you. But possibly not someone who is better than you in all ways, or even in all aspects of their career.

Why Partial Mentors Can Be Greater

The relative rarity of all-encompassing mentors is one reason why you shouldn’t obsess over finding them. But another is simply that the relationships you make with partial mentors can be more equal and mutually beneficial.

Consider becoming friends with that person who is ten steps ahead of you in career or business. If that person would sit you down and patiently give you advice and suggestions, you might really benefit. But how are you going to similarly benefit this person?

There’s a whole host of reasons why mentors want mentees. But the biggest is simply when the relationship is directly valuable. If this person can learn something useful from you, or you otherwise serve as a useful contact, the relationship is going to be less one-sided.

Partial mentors, therefore, are valuable because the chances that you have something worthwhile to share with them is much higher.

My Experiences with Both Types of Mentors

In my own career, I’ve had plenty of experience with both types of mentors.

I have friends who are clearly ahead of me in experience, and from whom I’m usually taking advice (not the other way around). I try to help them however I can, but it’s clear we’re not on the same level. As a result, our interactions tend to be briefer and more one-sided.

On the other hand, I have a much larger circle of peers that are better than me at some things, but for whom I’m good enough at others to also help them. This larger circle is much easier to talk with, have more frequent calls and discussions, and even offer mutual support.

I recently decided to work on a project to try to improve the traffic on my website. As a result, I talked to one of my friends who is an expert in SEO. Another who generates a lot of traffic with his website, and still another who has had impressive success with social media.

Individually, I wouldn’t want to completely emulate what any of those three people do in isolation, but in combination their suggestions were better than any I could have reasonably achieved from a perfect mentor who was doing exactly what I wanted. Best of all, because these people are not so far ahead of me, I can also offer something in return, say from my experience running courses.

Seeking Out Partial Mentors

The first step is to drop the expectation that someone should be better than you at everything in order for you to learn something from them. Mentors don’t need to be strictly higher than you in whatever social hierarchy you experience.

Second, try to cultivate friendships with people whose skills are broad and diversified. Therefore, you may not have one single person who is amazing at everything, but when you consider your social group as a whole, its collective intelligence ought to greatly exceed your own.

Third, try to size up and identify your relative value that you can contribute back to these partial mentors. What can you add that they don’t possess? Which skills, knowledge and experiences do you have that you could presumably help them with. Be generous with your talents and others will be with theirs.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.