If you exercise fairly regularly, it’s easy to say you have an exercise habit. Except, maybe you don’t always do the same exercise, sometimes you go running, swimming or lift weights. Maybe you don’t always work out at the same time of day or under the same conditions.

In these cases, even though you exercise regularly, it’s probably more accurate to say you have a commitment to exercise rather than an exercise habit.

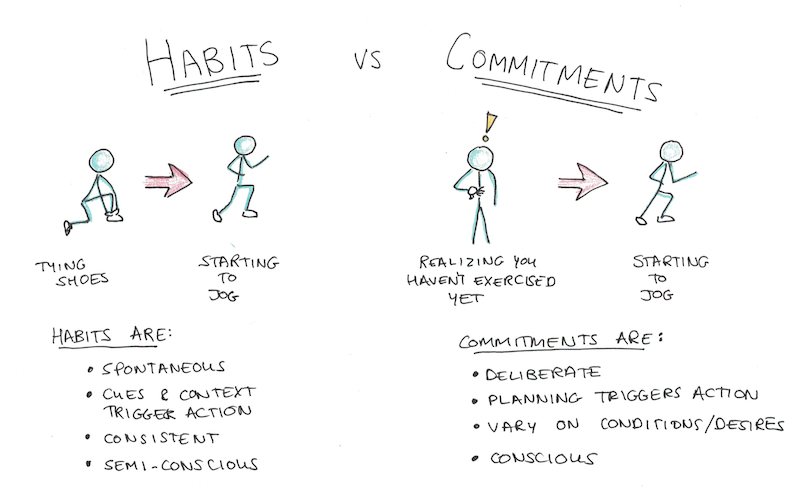

A habit is more than just doing something often. To be a habit, a behavior should come with a degree of spontaneity, triggered by a particular context. Habits may require some conscious monitoring (few people accidentally end up at the gym), but the level of conscious effort required should be fairly low.

A commitment, in contrast, doesn’t need to come automatically. It can require a lot of effort and energy, but you do it anyways because you’re following a rule in your head that says you need to do it, so it happens even if it doesn’t always happen automatically.

Which of Your Behaviors are Actually Habits?

To be fair, the difference between habit and commitment is not black and white. Exercising when you’re completely out of shape is a lot more effortful and deliberate than exercising when you do it regularly, albeit not always consistently from the same context.

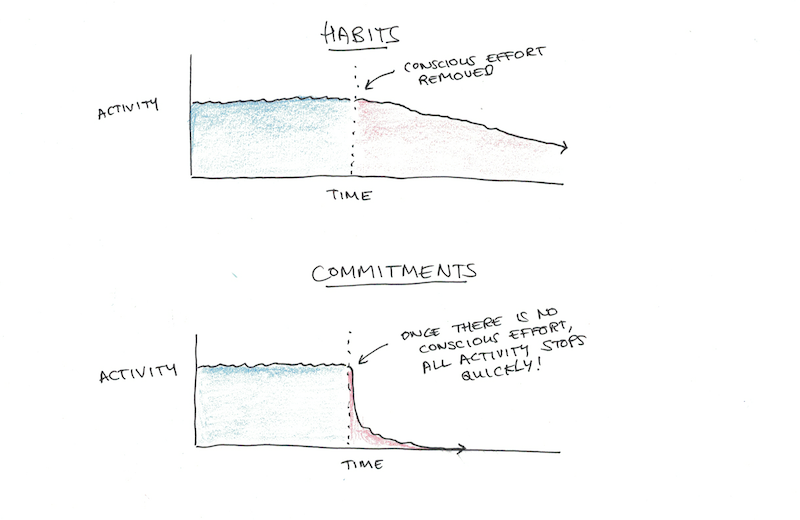

However, I’m making a distinction between the two because I think it’s fairly easy to think of yourself as having a habit to do X, but what you really have is a commitment to do X. The difference being that, once conscious effort withdraws (or you stop enforcing your rule to do X) commitments tend to be more fragile than habits.

In my own life, for instance, I have a commitment to do fifty push-ups every day. This is like a habit, except I don’t always do it at the same time or place. Sometimes I do them at the gym. Other times before bed (if I forgot to do them earlier in the day).

If I dropped my self-conscious tracking of my push-up habit, it would quickly fall back to not doing push-ups. Even after having done them for nearly a year, I still need to remind myself to do them. I don’t accidentally start doing push-ups.

In contrast, I’ve been working on a different commitment, reading/listening to Chinese for ten minutes per day. This has led to a semi-conscious habit of reading random articles in Chinese on my phone when I have downtime. This is more like a habit, because I do spontaneously engage in reading, even if I also have a commitment to do ten minutes per day.

Can You Make Your Commitments into Automatic Habits?

There’s nothing wrong with having commitments to do something consistently over time, versus an automatic habit which occurs largely without conscious planning or thinking. Once again, there are shades between the two where something requires less effort but still doesn’t happen perfectly automatically.

However, I still think it might be worthwhile to consider what makes commitments into automatic habits, since the latter seem more stable, and, lacking conscious effort to propel them forward, would seem to require only a small degree of maintenance rather than continuous monitoring to get done.

Here are some possible remedies for making commitments into habits:

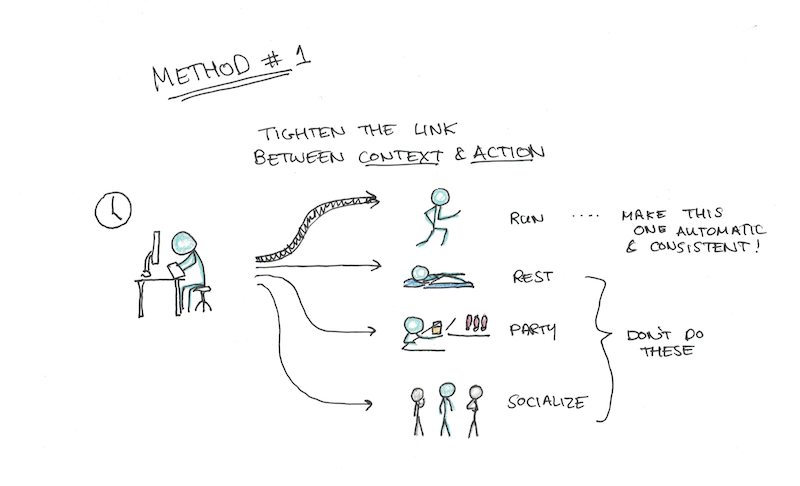

1. Tighten the link between context and action.

If you don’t always act out your habit under the same contextual triggers, or you sometimes act it out in some circumstances and you act it out differently in other circumstances, you’re less likely to end up with a habit.

Take our frequent fitness example. If you always went to the gym right after work, this is more likely to become a habit because ending work always cues up the behavior of going to the gym. Similarly, if you always go to the same place and do the same workout, the behavioral coupling will be stronger.

This also helps explain why initiating a behavior is the hardest thing to automate. Once you start some set of actions, the contextual cues narrow dramatically and the subsequent behavior is much easier to sustain. Unfortunately, real life often offers a much more variable set of contexts and cues prior to initiating some action, so getting started is harder.

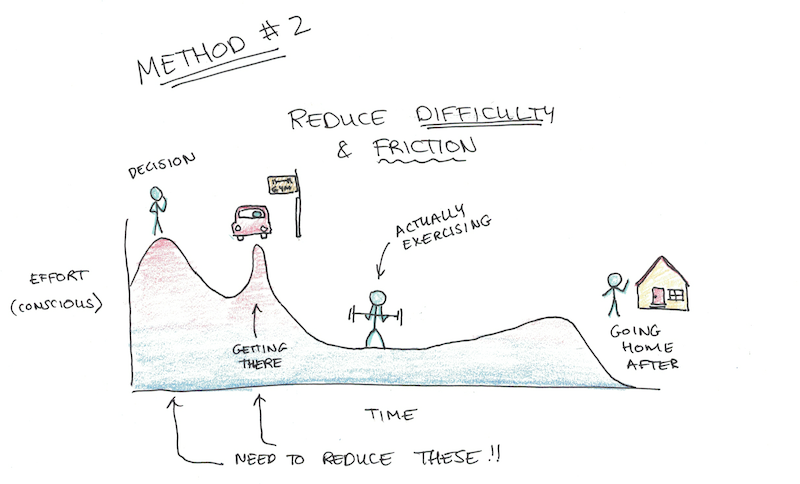

2. Reduce difficulty and friction.

Most habits are meta-stable. That is, they can be sustained with low effort for a time, but they are sensitive to falling apart due to random noise in the environment. Exercising is a meta-stable habit while not-exercising is stable, because the former degrades into the latter when things make it harder to exercise.

Of course, if your habit is easier, more rewarding and has fewer preconditions, it will be more stable.

Some of this is unavoidable. If you want to do something hard, you’ll just have to accept that it’s going to be less stable in the long-run.

However, if your goal is stability itself over accomplishing something of a given difficulty, then lowering the difficulty can make things much easier to do. If you want to read more books, for instance, you might start with books that are fun to read since this will be a more stable habit and will eventually expand your reading skills to handle more complicated works easily.

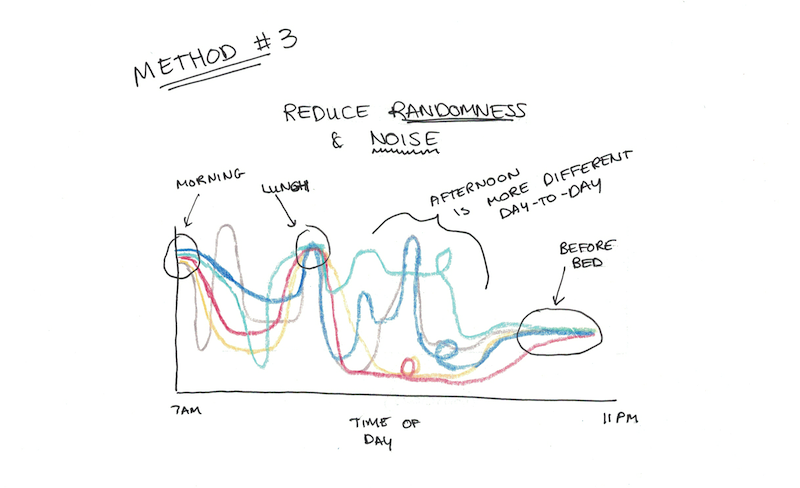

3. Reduce randomness and noise.

If you can’t make the habit easier, then an alternative is to reduce the chances something from the outside will derail it. This sounds impossible in a modern life, but this is always possible to some degree by choosing when and how you execute the habit.

One way is to work on your habit during a time of day when you’re less likely to face interruptions or obstacles. First thing in the morning or last thing before bed are usually safer times to do something than in the middle of the day, when interruptions are more likely. Similarly, you can do something right in the beginning or end of work, which are more consistent.

I’ve known other people who deliberately make parts of their routine more consistent, ostensibly to make behaviors that go along with them also more consistent. Mark Zuckerberg, for instance, is famous for wearing the same shirt every day, and Warren Buffet drinks Coca Cola with his lunch. These drives for consistency may have different motivations that the one I’ve stated here, but the impact is the same: creating consistent cues can also reduce the chance you’ll be derailed in your habits.

Is Automatic Habits a Reasonable Goal for All Behaviors?

I’m not certain that it’s possible sustain every goal through fully automated habits. Even people I know who are quite devoted to installing habits in their life, seem to use a mix of habits and commitments to accomplish the things they need to.

Many parts of life are just going to be too unstable or variable to allow you to reach a point where all action comes effortlessly.

That being said, I think you can make efforts to shift some of the things you already do regularly in the direction of genuine habits so that they happen with a little less force.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.