I’ve written before about how I first got interested in speed reading. I had read a book teaching it, and noticed it helped me read almost twice as fast.

A few years after, however, I mostly stopped using the technique I had learned and went back to the normal approach to reading. A few years after that, I decided to dig into the research and found that, while speed reading isn’t entirely without merit, it tends to increase speeds at a big cost to comprehension. That is to say, speed reading is more like controlled skimming.

One thing I did discover from my research, however, was that there is a reliable way to improve your reading speed and increase your reading comprehension: read a lot more.

In other words, although specific reading techniques (like pointers and eliminating subvocalization) probably don’t help too much to read faster without comprehension loss, simply reading a lot more is a great strategy to become a faster reader.

Why You Read Slowly

Reading is not a natural human ability. Unlike vision, hearing or language, it is not a skill hardwired into our brains. Instead, it is a skill that we acquired, culturally, by co-opting other developed cognitive strategies (such as image recognition and linguistic parsing).

As a result, although all normal children will learn language without intervention, literacy is something that doesn’t come automatically to us as a species.

In a recent fascinating book, The Reading Mind, cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham deconstructs what we know about the cognitive processes involved in reading, to try to give a sketch of what allows people to read, and what obstacles get in the way.

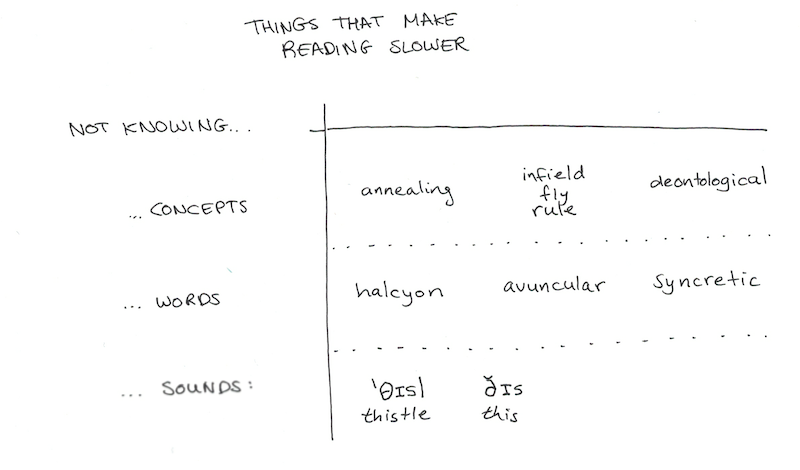

Constraint #1: Not Knowing the Topic

One of the big constraints on reading speed is simply content knowledge. If you know more about the topic being discussed while reading, you can read faster with greater comprehension since your mind will be better able to parse together the meaning of what you’re reading.

Consider one experiment which tested students on a text describing a soccer game. Students who were classified as “high verbal skill” scored slightly better than those with “low verbal skill” on a later test. However, the big difference was on their knowledge of soccer. Students who knew more about soccer scored much better than those who didn’t.

Although this experiment was on memory, not reading speed, since the goal of reading is generally to be able to understand and remember what was read, it’s still an increase in efficiency.

Constraint #2: Not Knowing the Words

At a lower level than the topic, vocabulary impacts your reading speed. Importantly, as Willingham distinguishes, it’s not just knowing the dictionary definition of a lot of words. Equally important is having a deep association with words so that you can fluently understand them as written in a lot of contexts.

This is obviously a problem when you’re reading in a second or third language. I read in Chinese and Spanish much slower than in English because many of the words I either do not understand, or they’re being used in a way that doesn’t make sense given my mental definition of those words.

However, even in your native language, writers tend to use a more complex and varied vocabulary than speakers. As a result, you may struggle to read with 100% fluency in your native language if you don’t know what every word means, or all the nuances of how they are being used in what you’re reading.

Constraint #3: Not Knowing the Sounds

Finally, at an even lower level than this, understanding how spoken language breaks down into component parts. Dyslexia, for instance, is often presumed to be a problem of visual recognition—that is flipping b’s and d’s around in while decoding the symbols.

However, research shows that the problem is probably more accurately a phonetic problem of breaking down words and sounds into individual letters. The difference between a b and p is actually quite slight (a puff of air in the latter), and these sounds are changed based on which sounds precede and follow them (the ‘p’ in port and the ‘p’ in sport are different). Other times different sounds link to the same symbols (say the first syllable of “thistle” and “this” and note the difference).

Phonetic knowledge is less of an issue for advanced readers, but it can still make decoding words and reading a chore, particularly in languages where you’re less familiar.

How to Read More to Read Faster

If reading is effortful, you’re going to want to do less of it. Therefore, if you want to read more, you need to spend more time reading things you find interesting and which are easy enough that you won’t need to push yourself to read them.

Krashen’s input hypothesis for language learning argues that, when learning a new language, you need to have huge volumes of input that are at a level where you understand almost everything you read. The idea here is that if you understand less than 95% of the text, it will be too difficult to sustain your motivation to keep reading. Graded readers and choosing texts you can readily understand, therefore, is a good motivation to keep reading.

My own suggestions for reading more are as follows:

1. Always have books for pleasure.

It doesn’t matter what they are, but always have books that you’re genuinely interested in reading. That could be light fiction, but it could also be a book about a topic you’re really interested in, and therefore, you’ll put in a lot of time reading it.

2. Don’t finish all your books, don’t be afraid to switch books.

These days, I tend to have 3-5 books in my “active” pile of books I’m currently reading. I tend to get bored of some books, or I’ll have new books arrive that will catch my interest and I’ll want to start reading them right away.

A lot of people worry that by not disciplining themselves to finish books that they’re “wasting” them, or that they’ll only read the easy books.

I think this reasoning is flawed. For one, there are more great books in the world than you’ll ever have time to read, so there shouldn’t be a motivation to finish a particular one over the countless others you’ll never even start. Second, more books read = greater fluency = greater enjoyment of reading = easier to read harder books. If you’re struggling to get through a hard book, switching to something you enjoy more may actually wind up leading you to more important books down the line.

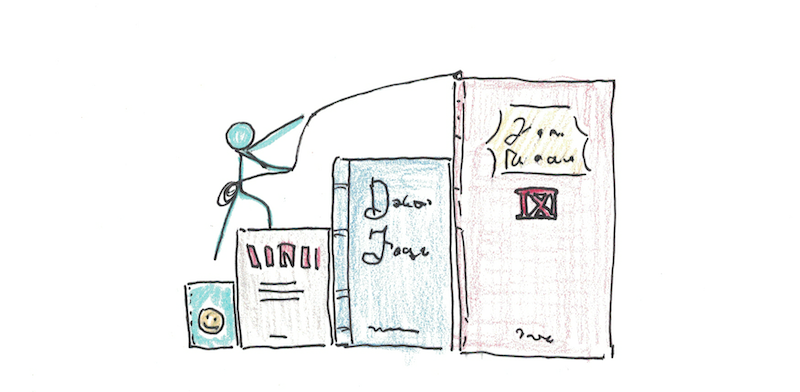

3. Build up to harder books.

If there’s a really difficult book you want to read, start by reading more accessible commentaries, or related books that will make you familiar with the topic, ideas and vocabulary. This will give you some background knowledge which will make reading the harder book easier.

Content knowledge is a big part of reading more fluently and efficiently, so if you’re struggling to read a book it might simply mean you need more background knowledge to process it properly. If you’re picking books, the most important thing is that they’re at the right level for you.

4. Build Your Foundation First

Both knowledge of the topic and knowledge of words can impact your reading rate. If a book expects you to know a lot of things you don’t, or it is using terminology you don’t understand, that can significantly slow your reading speed.

However, the flipside to this is that the vocabulary any given author uses is usually more restricted than all possible words. Similarly, there’s only so many concepts or ideas in the background of any particular book.

If you’re struggling with reading a book, therefore, spend the time to look up all the words you don’t understand, search the concepts on Wikipedia or google around for the stories behind names and characters you don’t recognize.

This will initially take more time, but it will eventually help you read the rest of the book much faster.

Get Reading!

There may not be a magical method to read rapidly without sacrificing any comprehension. But there is a sensible one–read more. As you invest more time reading, it will get easier and easier (as well as faster and faster).

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.