I’d like to talk about one of the most important things you can do for learning. It’s scientifically demonstrated to have a huge impact on your memory, attention and energy levels. Yet, tragically, it’s often the first thing many people jettison when they’re preparing for a big test.

The Most Powerful Learning Technique

The technique is sleep.

Sleeping 7-8 hours per night has an enormous impact on your ability to learn. Cutting sleep, even for as little as one night, can have irreversible impacts on what you learn both before and after, in your fatigued state.

Pulling all-nighters should be banned from your life as a valid tool to cram information. The costs are simply too high.

Even if you’re not staying up for days on end trying to learn, few of us get the sleep we need to learn at our best.

What You’re Doing When Sleeping

Sleep is not a passive activity. Although it seems like you’re doing nothing but resting, the mind is highly active during your moments of slumber.

Sleep is broken into different discrete phases, mostly falling into two catagories of REM (rapid eye-movement, aka dreaming) and NREM (non-REM, which includes deep sleep).

While your head is on the pillow, your brain is engaging in very important work. This includes:

- Allowing glial cells (support cells between neurons) to shrink in size, so that chemical byproducts that result from waking activity can be flushed away with cerebrospinal fluid.

- Spindle events, 10-12 Hz electrical pulses, which are believed to play a role in making declarative memories permanent.

- Reorganization and consolidation of learned information, possibly related to improving the ability to reason abstractly and extend knowledge to new situations.[1]

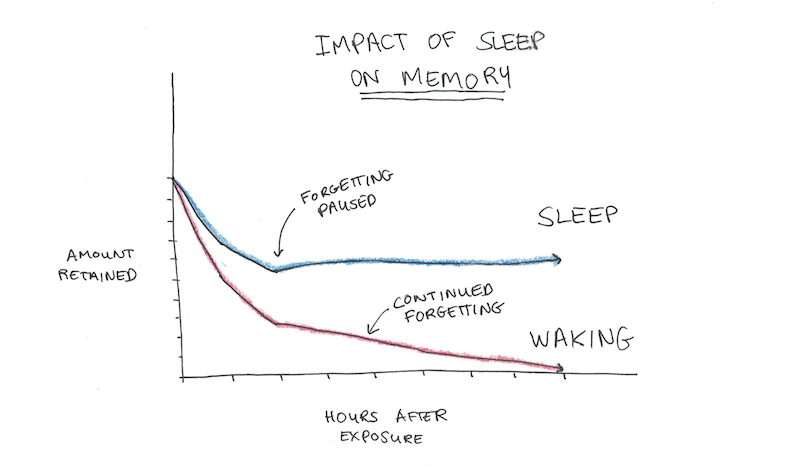

One of the first studies to demonstrate the importance of sleep to memory was the 1924 study by John Jenkins and Karl Dallenbach. In it, they compared rates of forgetting over the same time period when subjects were awake and asleep. The results are quite dramatic:

NREM sleep plays a particularly important role, with sleep researcher Matthew Walker explains:

“Indeed, if you were a participant in such a study [on sleep and memory], and the only information I had was the amount of deep NREM sleep you had obtained that night, I could predict with high accuracy how much you would remember in the upcoming memory test upon awakening, even before you took it.”[2]

Sleeping Pills, Alcohol, Caffeine and More

The importance of natural, healthy sleep (as opposed to merely being unconscious) means that you should be wary about the substances you ingest if you want to get the learning-accelerated benefits of a proper night’s sleep.

Drinking, for instance, is widely believed to help with sleep. Unfortunately, the sedative effects of alcohol also inhibit the memory consolidation effects of NREM sleep.[3] Therefore, a night out drinking can be nearly as bad as a night without sleeping in terms of the impact on your memories.

Sleeping pills also prevent many of the healthy benefits of regular sleep, so they can compound your problems with insomnia and make them even worse. Instead, Walker argues in favor of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, which research suggests should be the first-line treatment, rather than pills.[4]

Amphetamines and other drugs commonly employed by students to achieve higher levels of focus can also interfere with sleep, particularly if they’re taken later in the afternoon. Thus the caffeine you drink or stimulants you think will help you study better may end up making your learning much less efficient.

Even artificial light can delay your circadian rhythm, making it harder to fall asleep at an early enough hour to get proper rest.

What Should You Do Instead?

I recommend a two-fold approach to get the benefits of sleeping, not only for memory consolidation, but for improving your energy, attention, emotional stability and mood:

The first is to recognize that sleep is an active part of learning. Cutting sleep to spend more time studying is counterproductive. No approach to learning should make sleeping less than 7-8 hours per night a part of the plan.

The second is to put a plan in place to sleep better. Even if you recognize that sleep matters, it’s still easy to have your habits fall short of the ideal. There’s a few steps you can do to maximize your learning advantage through proper sleep:

- Limit alcohol and caffeine. Better that these happen earlier in the day than later, where they will disrupt proper sleep.

- Avoid screens and bright lights after 9pm. This will help you fall asleep faster.

- Sleep and wake at the same time every day, including weekends. Switching between late weekend nights and early weekday ones will make it harder to sleep well.

- Never sacrifice sleep for more studying. If you really have a lot to learn, you’re better off making use of the sixteen waking hours you have available. An hour sliced from sleep will hurt more than an extra hour with the books will help.

- Eight hours per day is the goal. Some people believe they can operate on less. Unfortunately, science says that they can’t, although they can fool themselves into believing they can.

A good way to think of the connection between sleep and learning is like the connection between exercise and recovery for an athlete. Elite performers know that it’s not enough to train non-stop. You need to give the muscles time to recover in order for them to grow stronger.

While the brain is not a muscle, there is an analogous truth about sleep and learning. Without sleep you can’t consolidate what you’ve learned. Instead of forming permanent memories, you’re more likely to overwrite what you’ve learned previously.

Improve Your Learning with More than Just Sleep

If you find lessons like these helpful, you’ll enjoy Rapid Learner. This is my full program for turning you into a more effective learner. I’ll guide you through the step-by-step process you can use to learn anything, whether it’s a language, class, skill or hobby, as effectively as possible

[1] – Hobson, J. Allan, Charles C-H. Hong, and Karl J. Friston. “Virtual reality and consciousness inference in dreaming.” Frontiers in psychology 5 (2014): 1133.

[2] – Walker, Matthew. Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. Simon and Schuster, 2017. p. 114

[3] – Ibid. p. 271

[4] – Ibid. p. 285

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.