Reaching any goal requires motivation, self-discipline and commitment. But where do those things come from?

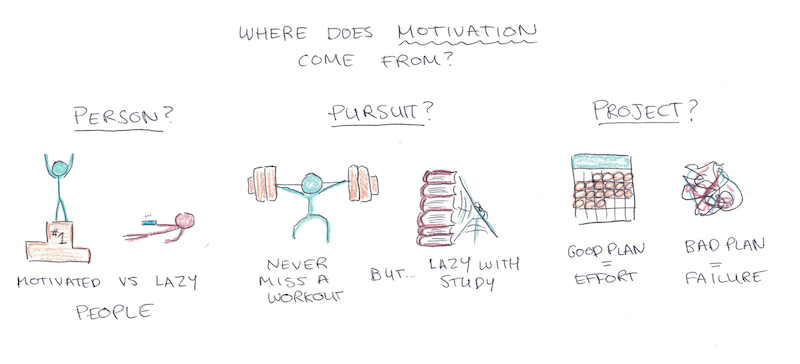

Many people see these as personality traits. Some people are motivated, others are lazy.

Other people recognize that they are sometimes lazy and sometimes motivated. So they add a little nuance and say that it depends on the pursuit. You might be lazy about cleaning your house, for instance, but never miss a gym day

I think the truth, however, is even more extreme than this. Motivation, self-discipline and commitment aren’t mostly about personality or the pursuit. Rather, I believe much of the difference between motivation and laziness comes from how you design your projects.

Human Nature is a Lot More Situational Than You Think

It’s been well-studied by psychologists for decades now that human behavior tends to depend more on situations than on persistent attributes of individuals.

Whether people will steal something depends a lot more on varying the context around the theft than from choosing between people who are inherently thieving or honest. Whether people cheat on tests depends a lot more on the environment than character. Whether people will help a bystander or ignore him depends more on situational factors than deeply-held convictions.

This is a deep truth that goes against a lot of our intuitions about other people. We tend to think people act a certain way because that’s the kind of person they are, rather than because that’s the kind of situation they are in.

This bias towards believing how people behave is mostly character and personality, rather than situation and environment, even has a name: fundamental attribution error.

How to Focus on Hard Goals

During my recent livestreamed ultralearning project to learn quantum mechanics, a number of visitors asked how I was able to focus on studying for so long.

The easiest explanation is that I’m somehow hard-wired for focus. Alternatively, you might wonder whether I just love physics so much I can concentrate for hours.

Yet, I don’t think these are the most important factors. Why? Because before I set up my project I had tried to learn the class previously. It went how you expect: I would start watching lectures, get distracted, never work on any hard problem sets and so on.

Similarly, when my project finished I wanted to learn the next class, 8.05. Had I changed and now adopted a successful approach? Nope, I was back to the same approach from before–watching lectures for a few minutes, getting distracted, avoiding the homework.

What was different during my one month project was how I designed it. Making it a priority, setting aside the time, creating motivational pressures, accountability and more.

How to Design Motivation Into Your Goals

If there were a simple formula, goal-setting would be easy. Instead, designing your goals so they generate the motivation required to reach them is hard. That being said, there are some factors you can adjust to improve your results:

1. Does Your Project Have Clear Standards?

Watch out for vague ambitions. Effort is never automatic, so if your ambitions are hard to define, it’s easy to slide back on them when you feel lazy.

There’s a million ways to choose these standards. I’ve already talked about maximum, minimum and average targeting. Constraints can be for outcomes (trying to complete MIT’s computer science curriculum in a year.) They can be about process (not speaking English to learn languages.) They can be habits (50 push-ups a day.) Or they can be to-do lists and milestones.

Standards form the constraints which keep you from sliding backward.

2. Do You Believe You Can Meet the Standard?

There’s always a tension between rising to the challenge set by the standard and rejecting it entirely. If you believe your standard can’t be met, you’ll reject it and give up.

Good standards, therefore, are ones you believe you can reach. They should also be ones that are less likely to get frustrated by outside circumstances, making them impossible for reasons you can’t control.

You’ll notice that this can create a positive feedback loop. Strong confidence results in lots of effort. Low confidence and even easy goals can’t be met. Bootstrapping this confidence spiral is a long-term effort, but it helps explains why some people are very ambitious and others are not.

3. Does the Standard Help You Reach the Result?

Clear standards are useless if they don’t actually help you reach your goal. Trying to lose weight by cutting out soda probably won’t help much, since you’ll probably just eat the calories somewhere else.

Standards for your actions are easier to enforce and motivate. Standards for outcomes can be more fickle, but they ensure you stay on target. A good project combines both so you reach your goal and maintain your motivation

4. Are There Immediate Incentives for Meeting (or Failing to Meet) the Standard?

Not only having clear standards, but immediate incentives for keeping them is important. A lot of goals only have diluted, long-term benefits for sticking to them.

A key skill of maintaining motivation on hard goals is constantly breaking down the goal into steps that need to be worked on now. If your only goal is to pass an exam that is months away, there’s little incentive to work now. If you need to finish chapter 2 by this afternoon, you have a push to get working.

5. Is Meeting the Standard a Priority?

No project you create exists in isolation. Every other part of your life is always being implicitly weighed against putting in effort into a project. Low-priority projects will fail when other things take precedence.

This is part of the reason I prefer either easy habits or intense, short-term projects. Easy habits aren’t priorities, but they also are easy to maintain. Intense, short-term projects may consume your life, but because they’re short, you can make space for them rather than try to juggle too many things simultaneously.

Projects you aren’t willing to put first won’t get done. Most goals fail before they begin because they aren’t a priority.

Other Advice on Structuring Projects

These are merely general features of good structures. Actual projects often have structures that depend on the specific situation. Careful choices here can make an enormous difference in your effort, motivation and outcome you experience.

If you choose wisely, you can do great things even if you’ve been lazy, unmotivated or uncommitted in the past. Choose poorly, however, and even the most committed person will make little progress.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.