In the last lesson, I showed why a lot of plans people make to avoid their work are misguided. Either the schemes don’t work at all (because they defy basic economic logic) or they result in escaping work only to leave a vacuum with nothing to fill it.

Instead, I argued, the better approach is to master your career. Build enough career capital so that you get to dictate the lifestyle you want, rather than meekly submitting to the ones other people would prefer that you follow.

Mastering your career, through building rare and valuable skills, isn’t easy. It can often feel as though you’re stuck—working really hard, but not getting anywhere fast.

Why You Get Stuck

K. Anders Ericsson’s work on deliberate practice was made famous by the 10,000 hour rule. Malcolm Gladwell had made the rule famous in his popularization of Ericsson’s research in his book Outliers.

The story told in the book, that becoming an expert requires an enormous amount of practice, has some appeal to it. However, as is often the case in science, the truth is more nuanced than the simplistic picture led on.

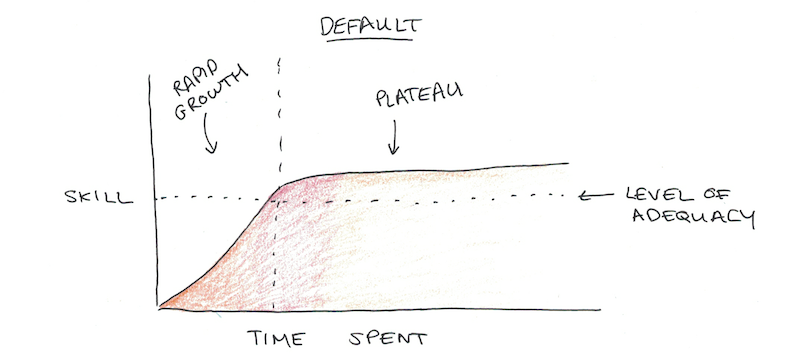

A common misconception of the rule was that putting in 10,000 hours was all that was required for excellence. Ericsson’s research, however, showed that this was far from the case. Most practitioners, whether they be doctors, athletes or chess players, reach an adequate level of performance and then stagnate.

Getting stuck, not moving ahead, is the default.

This also explains why many of us feel like we’re stuck in our careers. Getting stuck is the rule, not the exception.

Why Working Harder Doesn’t Work

It’s tempting to think that the way to get unstuck is to just work harder. While this is certainly an important part, just putting more effort in isn’t guaranteed to produce any results.

As you do the work in your job more and more, the habits you have for performing those skills become more and more deeply ingrained. Getting better requires pushing outside of those habits, and doing it systematically enough to get improvement.

It turns out that this is really hard to do. Just putting in more effort, if attention isn’t being paid to the right elements of your work, or if the environment isn’t optimized for deliberate practice, may end up simply reinforcing your old patterns, rather than upgrading them to new ones.

A Deliberate Practice Process for Your Work

While Ericsson’s research was instrumental in showing how deliberate practice contributes to expertise, it’s often not clear how to apply this in your profession.

Practicing layups, guitar solos or chess positions is easy to understand. But how do you practice a job, when much of what you do is write emails? How do you get better at something, when it’s often not even clear what skill is being practiced?

This difficulty was the major motivator behind Cal Newport and myself creating Top Performer. We wanted to know how you could identify the skills that mattered for your profession, and once you had done so, how could you get really good at them?

A Two-Pronged Strategy

After working with hundreds of students in the early versions of the course (as thousands since), the approach we found best for adapting deliberate practice to knowledge work was to focus on two different methods:

First, understand your career deeply by doing research. A lot of people struggle in their careers (especially in the beginning) because they haven’t yet learned how it works.

For instance, many non-fiction authors think the best way to write a bestselling book is to start by writing it. However, this isn’t how the industry works—getting an agent, writing a proposal and building an audience typically precede it.

If you’ve ever felt confused or bitter as to why some people seem to keep getting promoted in your office, while you get ignored, chances are you haven’t fully understood how your profession works yet.

One Top Performer student discovered that he had been missing out on promotions because, in his company, they were being given based on the dollars of value generated. He thought he was doing good work, but because he didn’t focus his efforts on delivering this result, he was being overlooked.

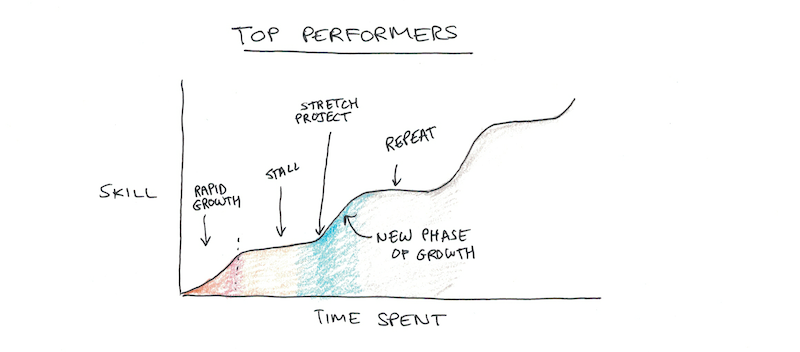

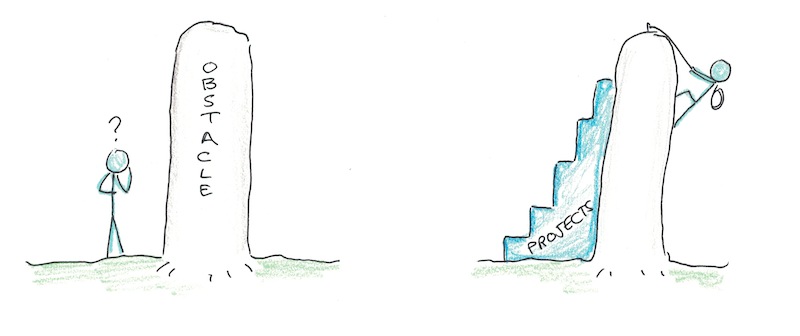

Second, once you understand your career, create projects that will force improvement in specific skills.

How to engage in deliberate practice was a tricky problem when we first started preparing the course. In the end, we found that designing projects was the right way to think about the problem. The right kind of project not only creates an environment where skill growth is possible, but it is often a lot more manageable than simply trying to get “better” in the abstract.

Of course, both doing research and designing projects have quite a bit of nuance, which is why Top Performer is an eight-week course, instead of just an article. However, this general strategy: figuring out how your career works, then designing projects to get really good at it, is surprisingly effective.

Over the course of running Top Performer, we have had quite a few students who have accelerated their careers, upgraded to six figure salaries or negotiated lifestyle perks that many dream about. Building a career you love isn’t easy, but it is worth the effort.

Top Performer will be holding a new session soon. Sign-up here to find out about when we re-open.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.